VOL. 2, No. 2

… unfinished, unclear, unrefined and unknown are words that may describe the quality delivery culture at the UWI OC. Keeping step with the times, we are working to change those descriptors to reinforced, rational, refined and recognised!

Abstract

With changes in the global economic landscape, universities are employing adjunct staff to instruct their online courses in new and expanding programs. Concomitantly, the growth of information and communication technology worldwide has facilitated the creation of classrooms without walls and universities without borders. The challenge for institutions is to create that nexus between programme quality and instructor engagement, especially where the instructors are just adjunct members of the staff. The University of the West Indies (UWI), through its virtual Open Campus (OC), has aligned its strategic objective of excellence to “…provide multiple, flexible paths for all constituencies to pursue tertiary education over their lifetime (UWI, 2012)” with the development of a framework that provides support for adjunct faculty members who are often “new to online”.

This article is predicated on a quality framework established within the UWIOC at the start of the academic year 2012/13. It draws on the processes used with online educators while the university restructured its quality assurance (QA) procedures. I will discuss how a quality framework might affect instructional practices in distance education while broadening the understanding of what it means to facilitate focused student engagement. Data for the study will be generated through multiple methods: ethnographic observations; focus group interviews and document and artefact collection – reports on the use of two monitoring instruments. I will analyse key components of the OC quality structure; quality context issues and their contribution to success; and essential principles for ongoing assessment and planning to maintain the cycle.

The discourse examines the possible effects of the changes, if any, through a practice-oriented perspective on quality amidst changes occurring within the UWI’s virtual campus. it also contemplates how the process of increased monitoring and accountability works towards quality improvement. Key findings are presented with graphic and narrative arrangements supported by literature in the area of institutional quality.

The growth of information and communication technology worldwide has facilitated the creation of classrooms without walls and universities without borders. The reaffirmation of UNESCO’s goal of ‘Education for all by 2015’ in Dakar brought many of the challenges for developing countries to the fore and raised the question of their collective abilities to reach the goal for the respective countries. One item from the Dakar framework, which resonates with educators globally is, “Ensuring that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programmes.” Keeping step with the times, The University of the West Indies (UWI), through its virtual Open Campus (OC), has aligned its strategic objective of excellence to “…provide multiple, flexible paths for all constituencies to pursue tertiary education over their lifetime ” with the Dakar framework for action.

This article is predicated on a quality framework established within the UWI Open Campus at the start of the academic year 2012/13. It draws on the processes used with online educators while the university restructured its quality assurance procedures. In this paper I discuss how a quality framework might affect instructional practices in distance education, while broadening the understanding of what it means to facilitate focused student engagement. I will analyse key components of the OC quality structure; quality context issues and their contribution to success; and essential principles for planning to maintain the cycle.

I also examine the possible effects of the changes, if any, through a practice-oriented perspective on quality amidst changes occurring within the UWI’s virtual campus. The discourse also considers how the process of increased monitoring and accountability works towards quality improvement. Key findings are presented using narratives supported by literature in the areas of open and distant learning (ODL) and institutional quality.

Several features of the UWI that are pertinent to the development of a quality culture are presented in brief below. The University began teaching in 1948 at Mona in Jamaica as a University College affiliated with the University of London, and became independent in 1962. Today, the UWI is a dual mode institution offering teaching by face to face and distance education modalities. The University has physical campuses at Mona in Jamaica, St Augustine in Trinidad and Cave Hill in Barbados. The Open Campus is the 4th campus which was created to reach the underserved populations affiliated with the UWI. The campus currently serves 17 Anglophone Caribbean countries—Anguilla, Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, The Cayman Islands, The Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Christopher & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & The Grenadines, The Republic of Trinidad & Tobago and Turks and Caicos.

The distributed locations of the campus and the use of adjunct facilitators (who serve students in diverse locations), have made it critical for the UWI Open Campus to create and implement quality assurance processes. To provide educational access to its underserved population and maintain quality, the UWI Open Campus provides programmes through distance modalities that offer flexibility of time, space and place through individualized curricula. The Adjunct staff that work at the UWI Open Campus are specialists in their fields of experience and provide examples for students which are applicable for the workplace. The changes in content and instructional strategies make it necessary to examine the quality of content and instruction to ensure quality, currency and reach for the changing small state economies. A quality framework facilitates uniformity in the area of andragogy and supports a standardized process.

In exploring open and distance learning for development, the Commonwealth of Learning (COL) describes the flexibility of ODL environments as “…the provision of learning opportunities that can be accessed at any place and time. Flexible learning relates more to the scheduling of activities than to any particular delivery mode.” (p. 1). Concurring with this principle, the UWI Open Campus has made its first small steps towards faculty development to ensure that the multiple, flexible paths to tertiary education and lifelong learning remain viable and accessible while maintaining the value of its educational product. While the university has embraced the significance of the relationship of ODL to its processes, unfinished, unclear, unrefined and unknown are words that may describe the quality delivery culture at the UWI Open Campus. Keeping step with the times, we are working to change those descriptors to reinforced, rational, refined and recognised!

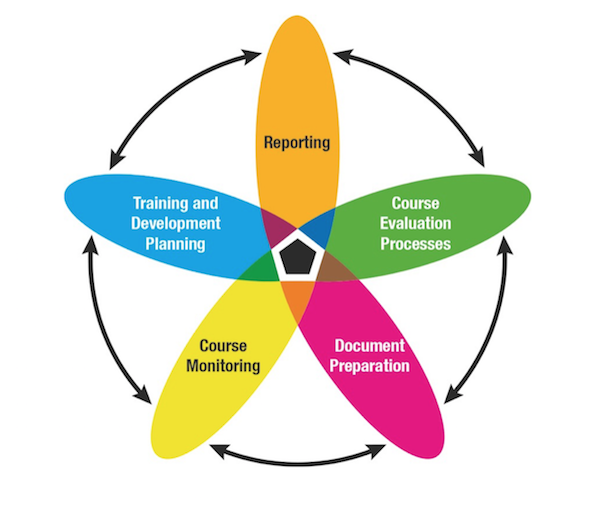

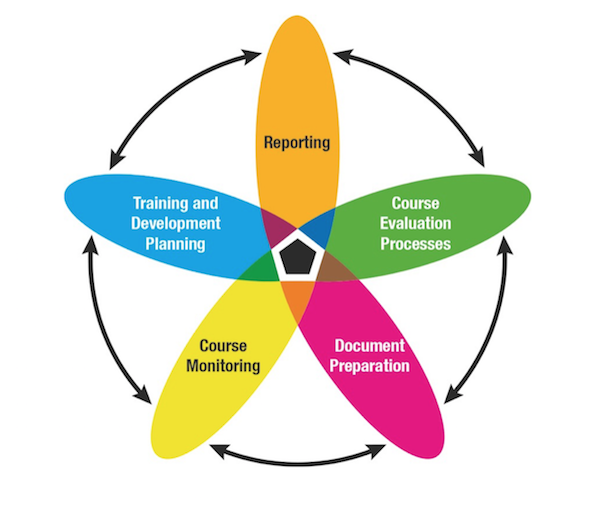

The campus seeks to accomplish its goal of creating a quality culture and maintaining its value through faculty guidelines and related actions predicated on the use of five key components for delivery:

Figure 1: Five key components of the UWI Open Campus quality structure.

While training and development planning, document preparation and course monitoring make significant contributions to the quality framework, they rely on the timing and frequency of prevalent components—course evaluation and reporting. These components form an interlocking whole, presented graphically in Figure 1.

The general principles related to the implementation of the quality delivery structure is summarised as follows:

A quality frame for the UWI Open Campus is created through adherence to the foregoing combined principles through an implicit agreement to adopt and advocate for the best practices that emerge through their application.

The most critical strategy in the development of a quality structure is to promote excellence in the delivery of courses among adjunct faculty taking into consideration the mission of the OC to create multiple flexible paths for lifelong learning. The OC has therefore included quality preparation of faculty in its delivery framework. This integration of quality into the training preparation and ongoing support is considered critical in ensuring that new and continuing faculty members possess the requisite knowledge, skills and abilities to operate in the ODL environment (Anderson, 2004). Anderson presents the view of “…the creation of an effective online educational community as involving three critical components: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence” (p. 273). In describing the “presences” Anderson introduces cognitive presence as the development of an environment where critical thinking and engagement occur with specific discipline based content. Social Presence, by distinction, is the development of a supportive environment where the learner is comfortable in expressing his or her ideas. The final of the three presences; teaching presence, embodies the multiple roles of the facilitator who is responsible for; creating the learning experience, creating strategies for engagement and going beyond moderating the experience to demonstrating content expertise.

Anderson (2004) believes that the needs of the distance learners should be assessed and preparation made to accommodate the prescription and negotiation of content through the teaching presence roles. At the UWI Open Campus, faculty preparation occurs through continuous engagement and the development of the presences articulated by Anderson. In this section, I explore what is implicit in Anderson’s three critical components, which encompasses and evaluates delivery and makes adjustments through the lens of expertise. The presences are examined against the background of support at UWI Open Campus for faculty engagement and the development of the facilitator roles and characteristics. I specifically examine the perspectives of five master tutors who responded to an opportunity to initiate changes in the course preparation and monitoring practices towards the development of a quality culture at the OC. Master Tutors are course facilitators who embrace and exemplify the components of the quality framework through best practices in their course processes. They encourage stake-holder buy-in and provide support with the initial training processes. The Masters mentioned in this paper are Pam, Claire, Anna, Eve and Janis, who work in the Management Studies, Educational Administration and Literacy programmes. Collectively, they have over fifty years of experience working in their disciplines at the tertiary level. They provide mentoring support for new facilitators and remain on call to support facilitator development and in-service training.

The sub-topics; possibilities, monitoring and implications, represent three critical steps taken by the UWI Open Campus in keeping with changing learner needs and global ODL development. These steps focus the discussion on salient ideas from Anderson’s research and the connection of the components the OC quality structure. Overall, the discussion here should prove valuable to new ODL faculty and programme administrators who are currently adjusting to changes in curriculum delivery and the expectations of a technology literate society where institutions use ODL to deliver continuing education programmes.

In this context, possibilities refer to the creation of the learning experience inclusive of initial and ongoing document preparation and the training support that is provided for the faculty member. At the OC, the ethos of excellence is founded on commitment to service delivery. The OC first selects content experts from various disciplines and establishes a common standard for the preparation of facilitators through training and ongoing support for the development of their teaching practice. Facilitators are encouraged to embrace diversity working towards the achievement of every student. Pre-planning considers the needs, which include; the learning style preferences, geographical locations and culture of all learners and match appropriate instructional strategies, assessment and opportunities for engagement that will cater for these needs. Anna’s views on the training options are below:

Vignette 1: The Role of In-service Training in the Quality Delivery Process Anna –“What have we been doing so far to ensure quality delivery? Many issues have been raised about the quality of online instruction. To provide quality online instruction, qualified instructors must first be prepared. So far, we have been preparing instructors who provide quality online instruction by:

Encouraging students to evaluate the courses continuously and periodically so as to improve online teaching I agree that there is more to be done, but YES! We can achieve quality delivery!” |

In keeping with the theme of development of social presence for the learner, monitoring enables the creation of a model of independence and accountability for the course facilitator. Feedback on quality processes is facilitated through the creation of monitoring instruments (see Appendix B) that are used by the programme manager to monitor course processes.

This allows acknowledgement of best practices and recommendations for training. Development of a social presence also helps to remove the transactional distance that mitigates negotiation processes in ODL. The seminal theory of transactional distance articulated by Moore (1993) remains current (twenty years later) and its principles validate our processes. It encompasses “…the universe of teacher-learner relationships that exist when learners and instructor are separated by space and/or time” (p. 22). The theory describes the relationship among the variables of dialogue, structure, and learner autonomy, and how these variables may be negotiated to increase or reduce transactional distance. The implementation of the monitoring process at the OC assures quality delivery by allowing insights into the strategies used to reduce transactional distance and promote them as best practices for decreasing distance. The views below represent the commitment of three master tutors to the quality structure:

Vignette 2: Achieving Quality Delivery Anna – “As a facilitator in the learning process, I pay attention to classroom dynamics and seek to create a supportive environment for students, within which they feel safe taking risks and making mistakes. Similarly, I see my own role not as infallible expert, but as someone engaged in reciprocal learning and dialogue with students.” Janis – “I certainly believe that we can and should strive for excellence in our standard of delivery. Many students come to us very apprehensive about the [prospect] of learning online. So that we are charged to reassure them that the task at hand is one which is manageable and once we commit to supporting their goals and maintaining the University’s standards certainly our customers will be very appreciative.” Eve – “We all come from different walks of life … [I’m] inspired and encouraged because we all have such varied experiences and come from varied professional backgrounds, yet we are united on the common basis of Education and the passion for facilitating education. It is this pride in what we do that should continue to lead us to strive for betterment and the pursuit of “quality”. This, however, I believe won’t come easily. As they say – “Rome wasn’t built in a day”…..it will take a lot of work and determination which I believe is well within our reach. What we do goes beyond the classroom – so we have to ensure we provide more than content knowledge. Students may be very shy and apprehensive, but they are very wise indeed – they know the level of involvement and effort and responsibility tutors have in their success; so we must communicate our expectations continuously and provide support – not only academic. A lot of what we are faced with is social, not only academic; so we must have a proper system to be able to gauge feedback / performance. Students sometimes tend to lack commitment to work / studying / reading, but it is critical, so we have a responsibility to provide support in this aspect – as their performance is a reflection on our work and our effort. As we progress through the semester; I am certain of the quality we will achieve. Let us keep in mind these [success] factors: leadership, motivation, teamwork, example, inspire, vision and training.” |

The final point in this section examines the implications of cognitive, social and teaching presences for instruction and knowledge development. Pedagogical principles and the needs of the adult learner along with the two previous points inspire the implications. The non-threatening environment for learner engagement and cognitive presence go hand in hand for the development of teaching presence. Facilitator roles are encouraged through course reports and evaluation; data collection, analysis, validation and use. Facilitators embrace their roles; demonstrate content expertise, create learning experience and select appropriate strategies for engagement. Their actions inspire learner confidence and foster a feeling of belonging in the learning community. In this development, the facilitator must master critical technology improvements and control of the learning management system operating within the institution. Support is provided for ongoing development in these areas to ensure that the ideas work together to maintain the culture of quality at work within the institution, two master tutors expand in the vignette below:

Vignette 3: Quality Involvement Pam – “I think we can achieve quality delivery…. From my observation persons are scoring high on the key areas indicated in the monitoring form. It suggests that there is a thrust towards quality. The sharing of best practices will also go a far way in attaining this goal.” Claire “…quality delivery is possible but not with apathy and 'otherness'. If we will achieve this currently nebulous quality at the OC, we cannot abdicate our own responsibility or leave the onus on that 'other’ person. We all are important parts of the process and whatever role we have is critical to our collective success. It is through this process of symbiosis and reciprocity that is found in working together that we will be able to achieve the institutional and programme quality we desire and deserve.” |

The quality structure emphasizes choice and allows the facilitators to make these choices, informed by learner evaluation of the courses. Ongoing monitoring by internal administrative staff increases the range of options for training and support and improves the teaching practice of adjunct faculty. As an ODL institution, the UWI Open Campus cannot afford to ignore opportunities for institutional development through faculty improvement. Rather, we have taken steps to face up to the challenges and changing needs of our institution.

Much progress has been made in establishing a quality culture at the UWI Open Campus over the last two years. The points presented identify the provisions and strategies for improved staff processes. The stakeholders at the UWI Open Campus have benefited from the structured process that the quality framework provides. This is evident in the courses across tutorial groups and locations where positive changes in quality standards are evident. We have achieved buy-in by adjuncts who are now requesting additional training and mentoring to meet the targets outlined in the quality frame. While the gains might not be considered as a giant leap, the steps represent the beginning of a valuable journey towards sustainability of this quality culture. The key strides are dependent on the stakeholders’ involvement, recognition and acceptance of diversity and a strong commitment to the process. The culture of quality created at the UWI Open Campus is sustainable through the efforts of all concerned over the long term.

Florence Gilzene-Cheese is Instructional Development Coordinator (Lecturer), Programme Delivery Department, Academic Programming and Delivery Division, The University of the West Indies, Open Campus. E-mail: florence.gilzene-cheese@open.uwi.edu