2023 VOL. 10, No. 1

Abstract: Adaptation to distance learning, which is one of the most effective ways of fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic, presented numerous challenges to society and the economy. The study aims to assess the consequences of distance learning as a result of the pandemic from the perspective of students and teachers. Quantitative research was conducted. The students (n = 417) and teachers (n = 47) of all disciplines from Tbilisi universities (Republic of Georgia) participated in the research. Non-probability convenience sampling technique was used for the study. Respondents evaluated the process of distance learning positively since they had the opportunity to attend lectures from any location, thus, saving costs, learning new skills, gaining valuable experience, and having more free time left than before. Using a Likert scale, the distance learning process was positively assessed by students (3.2 points out of 5) and teachers (3 points out of 5). The majority of students (n = 288, 69%) preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods as they consider the student’s own choices in a superior way. Respondents pointed out some deficiencies, such as limited communication, technical access difficulties, low quality and malfunction of internet access, an inconvenient environment, students’ involvement process and complicated social relationships. The crisis caused by the COVID-19 epidemic has identified the need to advance the methods of high-quality acquisition of knowledge. It is preferable to equip university auditoriums with the necessary technical capabilities and to develop curricula that allow students to decide whether to attend lectures in the classroom or to participate online.

Keywords: distance education, distance learning, online education, educational technologies, students’ perception.

In December 2019, a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection (COVID-19) was detected in Hubei Province, China. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus as a global threat, and on March 11, as a pandemic (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020). The first case of virus infection in Georgia was confirmed on February 26, 2020. On March 21, 2020, a state of emergency was declared for the entire territory of Georgia, and from March 31, a general quarantine regime was introduced.

COVID-19 continues to spread around the world, with more than 550 million confirmed cases and more than six million deaths reported across almost 200 countries. In Georgia, as of October 2022, there have been 1.7 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 16,900 deaths, reported to WHO (WHO, 2022).

Besides many health problems and challenges, the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on various aspects of human life (Cao et al., 2020). It affected social, economic, political, and educational processes (Brooks et al., 2020). To avoid further deterioration of the situation, it was necessary to take special measures based on the concept of social distance. Social distance allows us to avoid being in crowded spaces, as it increases physical space among people and prevents the spread of disease.

The majority of the pandemic-affected countries have successfully managed to slow the spread of the virus. This has been achieved by carrying out radical measures such as banning public events and gatherings, staying at home, restrictions on domestic and international travel, and the temporary closure of educational institutions (Owusu-Fordjour et al., 2020). The transition to distance learning is one of the most effective ways to reduce the spread of the virus, but despite that, it has created many challenges for both students and teachers, as well as for their families, friends, employers, and, consequently, for society and the economy (Rose, 2020).

The adaptation to distance learning has completely changed the normal process of teaching in educational institutions, and consequently, innovative teaching methods have been introduced. During distance learning, questions arise: Does it provide the same knowledge as we are used to in the classroom, and how much does it help students gain knowledge? How can we help students who do not have reliable access to the internet or students who are without the necessary technology to participate in distance learning?

Numerous articles have already been published about the various aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis – particularly, its impact on physical and mental health, the economy, society, and the environment (Kaparounaki et al., 2020; Iyer et al., 2020; Aker & Mıdık, 2020; Reznik et al., 2020). Among the reported challenges are organisational, technical and adaptation difficulties, lack of appropriate devices necessary for online learning, problems with internet connections, poor learning spaces at home, stress among students, and lack of fieldwork and access to laboratories.

Although there are few studies that report the online learning challenges that universities experience during the pandemic, limited information is available regarding the specific strategies that they used to overcome them. In this regard, it is interesting to study the changes that have taken place in the education system during the COVID-19 pandemic to make this process more effective.

The advancement of communication technologies led to a new method of teaching — electronic/distance learning. Distance learning is a form of education where teachers are physically separated from students in the teaching process. Distance learning using electronic technologies is not a new phenomenon and has been used in higher education institutions for many years (Leszczyński et al., 2018). Using electronic technologies has played an important role in increasing the productivity of teaching (Berawi, 2020). With the help of the internet, students can easily get the information they need and listen to the professor directly or asynchronously. Besides, they can contact the professor and solve problems remotely. Distance learning can be used in remote areas, such as rural areas.

There are asynchronous, synchronous, and mixed models of online learning. Synchronous online learning means that the teacher and the student have to be online at the same time, however, they may be in different places, furthermore, video/audio conferencing, electronic message boards, and webinars are used during the learning process. Apart from this, asynchronous online learning does not require both the teacher and the student to be online at the same time and is not strictly timed. This kind of learning process combines online courses based on digital media and forums, blogs, emails, and social networks. Also, there is a mixed learning method that combines the components of both, synchronous and asynchronous learning.

The sudden and quick transition from conventional learning to distance learning had a major impact on students ’attitudes toward the learning process (Verma et al., 2020). Students' practices related to academic work have changed (switching to online lectures, closed libraries, new assessment methods, etc.) (Kamarianos et al., 2020). Students' social lives changed (dormitories were closed, meetings with friends stopped, parties and trips were canceled), as well as their financial situation (job loss, uncertainty about their financial status, education, and future careers), and mental health (fears, frustrations, anxiety, boredom, etc.) (Perz et al., 2020; Pan, 2020; Elmer et al., 2020; Elmer et al., 2020).

Regarding positive effects, it should be mentioned that e-learning has made the education process more student-centered, creative, and flexible (Markus, 2020). Lecturers and students were forced to explore new methods of distance learning that had not been used before. E-learning creates a relatively free environment. There is more opportunity to communicate with people at any time. Stress has been reduced because the course of the lectures does not require physical involvement. The presence of teachers and students in one space helps strengthen relationships between them. In addition, online learning means constant engagement with teachers and as a result, it reduces unpleasant distance.

E-learning reduces the cost of education since it is more optimal and affordable and it does not require moving through space and time (Cheng, 2011). Studies show that distance learning platforms allow students to access a variety of learning resources without limiting time and space (Rienties et al., 2016). Online tuition is particularly effective and makes e-learning easily accessible for students living in rural and remote areas. It also reduces administrative costs associated with renting an apartment and buying teaching equipment (e.g., desks, chairs). One of the advantages of distance learning is the easy access to the study material anywhere after connecting to the internet and also it reduces the cost of transportation and renting an apartment (Molotsi, 2020). Self-directed e-learning allows students to manage their activities independently.

Despite the positive aspects of e-learning, studies emphasised the challenges associated with distance learning such as disorganised infrastructure, internet problems, technological difficulties, and lack of access to software and internet services. The level of electricity and internet infrastructure in Georgia is lower than average. Communication may be interrupted during lectures and students should re-login to continue the session. Technological underdevelopment interrupts full and adequate involvement in the online learning process. Inequality in technology and internet access is particularly noticeable for poor students (Adresi, 2020). A pandemic may widen the gap between students, which would negatively affect their education (Fawaz & Samaha, 2021).

Online teaching is especially problematic for students who study medicine, natural sciences, and other similar fields because there is a limited opportunity to conduct practical and laboratory work. For medical students, experience and education gained in the clinical environment is crucial and cannot be fully replaced by distance learning. To some extent, this problem can be solved by simulations with virtual patients (VPs) and real clinical scenarios.

The university environment and auditoriums offer students the opportunity to have direct communication with each other, which plays a significant role in the socialisation process between students. It includes students’ interaction and self-expression. This transition of the educational process to the online format has a negative impact on the psychological condition of students and has led to problems such as stress, social isolation, and depression (Othman et al., 2019). Social isolation and reduction of activities lower students’ motivation, which causes the feeling of unproductiveness. Studies have found a close connection between online learning satisfaction and psychological state (depression, anxiety and stress). The lower the level of satisfaction with online learning, the higher the rate of depression, anxiety, and stress that can be seen among students (Fawaz & Samaha, 2021).

The study aims to assess the opportunities and challenges of distance learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of students and teachers.

Thus, the objectives of the present study are:

Furthermore, the study addresses future implications and the potential of blended learning as a future solution.

A quantitative, cross-sectional research design was used for this study.

The students and teachers at all levels (undergraduate, master's degree, doctorate) and disciplines of Caucasus University, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, and Ilia State University (Republic of Georgia) participated in the research. These three universities were selected to represent both private and public universities.

Non-probability convenience sampling technique was used for sample collection (Stratton, 2021). The data was collected from June 2021 until the end of October 2021. The data was gathered at a specific time, and therefore, the study was cross-sectional. The universities received an email with the option of either forwarding or otherwise providing a list of their students’ email addresses so that we could contact them personally. The total number of questionnaires distributed among students were 500, and 417 responses were useful, resulting in an 83.4% response rate. The proportion of study participants varied according to stages. We included Bachelors (n = 336, 80.6%), Masters (n = 77, 18.5%) and PhD students (n = 4, 1%), and among them 26 (6.2%) were foreign students from all three universities who participated in the survey. The study was attended by 47 teachers, including visiting professors (n = 25, 54%), associate professors (n = 11, 23%), full professors (n = 9, 19%) and assistant professors (n = 2, 4%).

A pre-structured online questionnaire made via the Google Forms electronic platform was used as a research tool. It was developed based on the existing literature and was adapted to the reality of Georgia. Before taking up the research, the questionnaire was pre-piloted and, after piloting, minor adjustments were made to the questionnaire.

The questionnaire included socio-demographic data and closed-ended questions, and respondents could express opinions on both content and technical issues. The average duration for completing the questionnaire was 10 minutes.

The study involved pre-structured online interviews as a data collection method. The researcher employed pre-structured interviews to collect data from all categories of participants. The open-ended nature of pre-structured interviews motivated the interviewees to fully express their opinions and experiences, enabling the researcher to explore in-depth insider perspectives.

After finishing the research, the data was transferred and encoded in SPSS. Both one-dimensional analyses, in the form of frequencies, and two-dimensional analyses, in the form of cross-constructions, were used while analysing the data.

Before starting the study, we received approval from the Research and Ethics Committee of Caucasus University. Before participating in the study, selected individuals were given informed consent forms. Survey participants could voluntarily leave the survey at any time.

The questionnaire was accompanied by an instruction/description that included several indications that the survey was anonymous, and respondents did not have to indicate personal data that would allow them to be identified. The aim of the research was described in the description of the questionnaire.

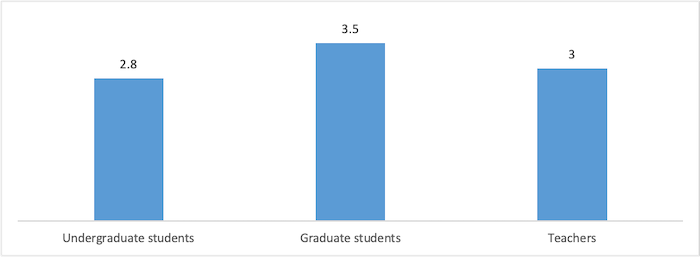

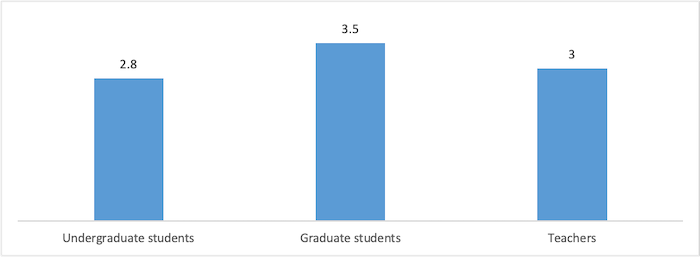

Respondents had to rate the distance learning process on a 5-point Likert scale where 5 meant very good and 1 very bad (Fig. 1). Overall, students rated the distance learning process positively, with an average score of 3.2 points. As for the distribution of point averages by levels, it was found that graduate students evaluated the process even more positively than undergraduate students. Undergraduate students rated the distance learning process with an average score of 2.8 points, while the average for graduate students was 3.5. The teachers who participated in the study positively evaluated the distance learning process. Their average point for distance learning was 3 points. The results show that there was no negative effect from switching from face-to-face to online learning. This was due to the fact that this is the generation of the digital age, who are familiar with online learning and have good digital skills.

Figure 1: Respondents rate of the distance learning process on a 5-point Likert scale

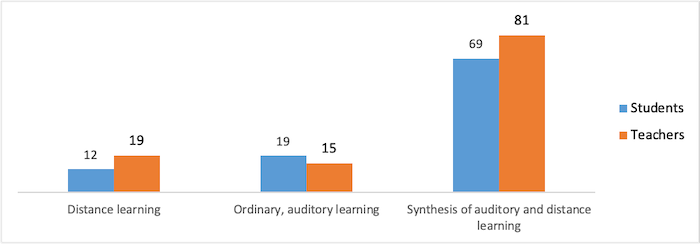

The majority of the students (n = 288, 69%) and teachers (n = 38, 81%) preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods (Fig. 2).

Figure 2:The preferred choice of distance learning method

Rural students (n = 44, 77%), urban students (n = 244, 67.7%), students who were unemployed (n = 288, 69%) and who worked and studied all at once (n = 84, 65%) were particularly satisfied with this method. Students’ answers to this question did not differ according to their gender; both male (n = 62, 68%) and female (n = 226, 69%) students preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods. Surprisingly, Georgian and non-Georgian students' attitudes towards the distance learning method were different. All the non-Georgian speaking students (100%) preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods. As for the difference between universities, Caucasus University students generally preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods to online teaching.

Female teachers (n = 25, 83.3 %%) prefer even more the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods, compared to male teachers (n = 13, 76.5%). The majority of teachers agreed (n = 18, 38.3%) or slightly agreed (n = 10, 21.3%) with the opinion that they needed more effort while teaching online.

Table 1: Which teaching method would you prefer?

|

Distance Learning |

Ordinary, Auditory Learning |

Synthesis of Auditory and Distance Learning |

All |

|||||

Student |

Teacher |

Student |

Teacher |

Student |

Teacher |

Student |

Teacher |

||

Sex |

|||||||||

Female |

40 (12.3%) |

1 (3.3%) |

60 (18.4%) |

4 (13%) |

226 (69%) |

25 (83%) |

326 (78%) |

30 (64%) |

|

Man |

10(11%) |

1 (5.9%) |

19(20.9%) |

3(18%) |

62 (68%) |

13 (77%) |

91 (21.8%) |

17 (36%) |

|

Residence |

|||||||||

City |

43 (12%) |

3 (7%) |

73 (20%) |

5 (11%) |

244(68%) |

36 (82%) |

360 (86%) |

44 (94%) |

|

Village |

7 (12%) |

0 (0%) |

6 (11%) |

2(33.3%) |

44 (77%) |

2(66.6%) |

57 (14%) |

3 (6.4%) |

|

Citizenship |

|||||||||

Georgian |

50 (13%) |

2 (4%) |

79 (20%) |

7 (15%) |

262(67%) |

38 (81%) |

391 (94%) |

47(100%) |

|

Foreigner |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

26(100%) |

0 (0%) |

26 (6%) |

0 (0%) |

|

Are you employed? |

|||||||||

Yes, I am a full time |

32 (35%) |

|

13 (10%) |

|

84 (65%) |

|

129(30.9) |

|

|

Yes, I'm a part-time |

18 (46%) |

|

10 (16%) |

|

33 (54%) |

|

61(14.6% |

|

|

I am not employed |

0 (0%) |

|

56 (25%) |

|

171(75%) |

|

227 (54%) |

|

|

All |

50 (12%) |

9(19.1%) |

79 (19%) |

7 (15%) |

288(69%) |

38 (81%) |

417(100%) |

47(100%) |

|

The majority of students did not agree (n = 200, 48%) or slightly consented (n = 103, 24.7%) with the opinion that the quality of learning has improved in the online learning mode, although according to their answers, the frequency of attending lectures increased (Table 3). The majority of teachers did not agree (n = 17, 36.2%) or slightly consented (n = 19, 40.4%) with the opinion that the quality of teaching improved when switching to online learning.

Students point out the advantages of the online teaching method along with the pros of synthesising distance and auditory learning methods. In general, the majority of students (n = 183, 43.9%) agreed and relatively agreed (n = 116, 27.8%) with the statement that while switching to distance learning, they spent more time studying (Table 2). However, more students agreed (n = 189, 45.3%) and relatively agreed (n = 154, 36.9%) that they have much more free time within this kind of learning method. The majority of students completely agreed (n = 171, 41%) or relatively agreed (n = 138, 33.1%) with the opinion that they are more able to attend lectures under distance learning conditions. In addition, a larger proportion of students surveyed agreed (n = 185, 44.4%) or relatively agreed (n = 147, 35.3%) that switching to distance learning gave them new, useful skills and experience. Moreover, a larger proportion of students surveyed agreed (n = 142, 34%) or relatively agreed (n = 192, 46%) with the statement that the quality of the university's transition to distance learning was acceptable.

The majority of teachers completely agreed (n = 26, 55.3%) or relatively agreed (n = 12, 25.5%) with the opinion that they had more free time left in distance learning conditions (Table 2). Furthermore, most of them (n = 32, 68%) admitted that they generally enjoyed working from home since they had comfortable conditions at home (n = 40, 85%).

Table 2: Assessment of distance learning

Strongly Agree |

More or less Agree |

More or less Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

|

I need more effort in distance learning than in the classroom |

||||

Student |

18 (4.3%) |

79 (18.9%) |

229 (54.9%) |

91 (21.8%) |

Teacher |

18 (38.3%) |

10 (21.3%) |

6 (12.8%) |

13 (27.7%) |

During distance learning, I am more able to attend lectures |

||||

Student |

171 (41%) |

138(33.1%) |

64 (15.3%) |

44 (10.6%) |

With the distance learning method, the quality of teaching in general is improved |

||||

Student |

25 (6%) |

89 (21.3%) |

103 (24.7) |

200 (48%) |

Teacher |

0 (0%) |

11 (23.4%) |

17 (36.2%) |

19 (40.4%) |

When using the distance learning method, I have more free time |

||||

Student |

189 (45.3%) |

154(36.9%) |

47 (11.3%) |

27 (6.5%) |

Teacher |

26 (55.3%) |

12 (25.5%) |

6 (12.8 %) |

3 (6.4%) |

Using the remote method, I gained new useful experiences and skills |

||||

Student |

185 (44.4%) |

147(35.3%) |

51 (12.2%) |

34 (8.2%) |

Teacher |

20 (42.6%) |

21 (44.7%) |

6 (12.8%) |

1 (2.1%) |

I have comfortable conditions for distance learning at home |

||||

Student |

183 (43.9%) |

144(34.5%) |

69 (16.5%) |

21 (5.0%) |

Teacher |

27 (57.4%) |

13 (27.7%) |

5 (10.6%) |

2 (4.3%) |

I generally like working from home |

||||

Student |

114 (27.3%) |

160 (38.4%) |

73 (17.5%) |

70 (16.8%) |

Teacher |

9 (19.1%) |

23 (48.9%) |

7 (14.9%) |

8 (17%) |

The quality of the organization of distance learning by the University is very good |

||||

Student |

142 (34.1%) |

192 (46%) |

65 (15.6%) |

18 (4.3%) |

Teacher |

30 (63.8%) |

14 (29.8%) |

2 (4.3%) |

1 (2.1%) |

With distance learning, more time is saved on learning |

||||

Student |

183 (43.9%) |

116 (27.8%) |

62 (14.9%) |

56 (13.4%) |

According to the majority of students surveyed (n = 211, 50.6%), they were generally ready to switch to distance mode, yet they also had to learn something (Table 3). In terms of previous experience, only 8.4% of students (n = 35) did not have the experience of attending lectures or seminars online before the pandemic and had to learn everything from scratch. Most of the teachers (n = 39, 83%) were fully ready to switch to distance mode, as they had already given lectures/internships online. Students’ and teachers’ positive attitude toward online learning during the coronavirus pandemic suggests that they had online learning skills before the pandemic. It should be noted that at the beginning of the pandemic, all students and teachers were given additional training in online teaching.

Table 3: How do you assess your readiness for a pandemic during the transition to distance learning?

I was prepared in advance to use the distance learning method in general |

I was ready to switch to the distance learning method, but I had to learn some things |

I was poorly prepared to switch to the distance learning method |

I needed to learn a lot |

All |

|

Student |

|||||

Undergraduate |

81 (24.1%) |

176 (52.4%) |

49 (14.6%) |

30 (8.9%) |

336(80.6%) |

Master's degree |

34 (44.2%) |

34 (44.2%) |

5 (6.5%) |

4 (5.2%) |

77 (18.5%) |

Doctorate |

2 (50%) |

1 (25%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (25%) |

4 (1%) |

All |

117 (28.1%) |

211 (50.6%) |

54 (12.9%) |

35 (8.4%) |

417(100%) |

Teacher |

|||||

|

16 (34%) |

23 (48.9%) |

6 (12.8%) |

2 (4.3%) |

47 (100%) |

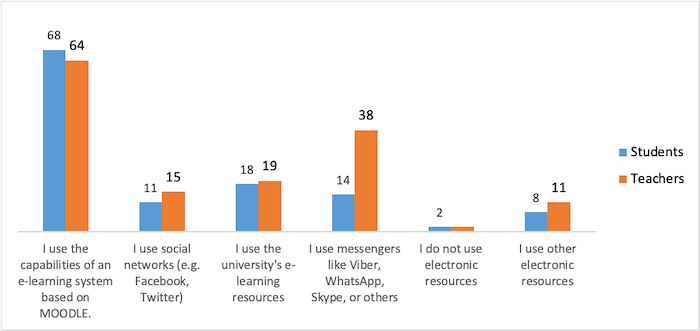

The majority of students (n = 285, 68.3%) mainly used Moodle's platform for online learning mode (Fig. 3). This rate is the same for both undergraduates and graduate students, as well as for students from different universities. Students also used the WhatsApp, and Skype platforms for online learning (14% of respondents). Most of the teachers (n = 30, 64%) mainly used the Moodle platform for the online teaching mode. However, they also used the WhatsApp, and Skype platforms (n = 18, 38%) and university e-learning resources (n = 9, 19%).

Figure 3: Electronic resources used in distance learning

Obstacles were faced up to when switching to distance learning mode. Most of the students surveyed (n = 189, 45.3%) stated that access to the internet was not significantly problematic, or not problematic at all (n = 166, 39.8%) and therefore they had access to online lectures on time (Table 4). Respondents for whom access to online lectures was very problematic were only 15.6% (n = 63). Similar results were seen from a survey of teachers. According to the vast majority of teachers (n = 43, 91.5%), access to the internet was not significantly problematic, or not problematic at all.

When switching to the distance learning method, the least problematic was the comfortable workplace for students (n = 88, 21.1%). Controversially, the most problematic thing for students was the lack of skills or experience when switching to distance learning (n = 53, 12.7%). According to teachers, the biggest obstacle in terms of online learning was the weak technical capabilities of the techniques used by students (n = 28, 59.6%). The least problematic thing for them was lack of skills or experience (n = 4, 8.5%).

Table 4: Remote Switching Problems

|

Very Problematic |

Pretty Problematic |

Not Greatly Problematic |

Not Problematic At All |

Proper technological equipment (computer, tablet) |

||||

Student |

13 (3.1%) |

52 (12.5%) |

186 (44.6%) |

166 (39.8%) |

Teacher |

0 (0%) |

3 (6.4%) |

16 (34%) |

28 (59.6%) |

Internet access |

||||

Student |

22 (5.3%) |

40 (9.6%) |

189 (45.3%) |

166 (39.8%) |

Teacher |

0 (0%) |

4 (8.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

43 (91.5%) |

Comfortable place to work |

||||

Student |

27 (6.5%) |

61 (14.6%) |

170 (40.8%) |

159 (38.1%) |

Teacher |

3 (6.4%) |

9 (19.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

35 (74.5%) |

Good communication from the university while in remote mode |

||||

Student |

25 (6.0%) |

44 (10.6%) |

166 (39.8%) |

182 (43.6%) |

Teacher |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (6.4%) |

0(0.0%) |

44 (93.6%) |

Lack of skills or experience in using distance learning on my part |

||||

Student |

17 (4.1%) |

36 (8.6%) |

196 (47.0%) |

168 (40.3%) |

Teacher |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (8.5%) |

0 (0.0%) |

43 (91.5%) |

Weak technical capabilities of the equipment used |

||||

Student |

11 (2.6%) |

52 (12.5%) |

197 (47.2%) |

157 (37.6%) |

Teacher |

28 (59.6%) |

17 (36.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (4.3%) |

Insufficient methodological or technical capabilities of the e-learning system |

||||

Student |

17 (4.1%) |

61 (14.6%) |

204 (48.9%) |

135 (32.4%) |

Teacher |

0 (0.0%) |

9 (19.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

38 (80.9%) |

Research has shown that the distance learning process was positively assessed by both students and teachers. Many students were satisfied with distance learning because they had more free time, since they did not have to waste time on travelling to and from university, and could spend more time studying some disciplines or engaging in activities they were interested in. Travel costs were reduced. Students who attended the lectures from the district villages were allowed to save on the cost of renting an apartment. In addition, they were more likely to attend lectures on distance learning. Similar results have been seen in other studies (Pelikan et al., 2021; Katić et al., 2021).

Students living in villages and remote areas were particularly satisfied with the distance learning method. Our findings are consistent with the results of Rahman (2021). Most of the respondents enjoyed working from home as they had comfortable conditions there. Lecturing remotely was more mobile, since both students and lecturers had the opportunity to join the lecture from any location if they had access to the internet.

According to most students, the distance learning method gave them new useful experiences and skills. It enables students to develop valuable skills independently. The student masters the skills of self-education, self-realisation and self-expression, learning, and working independently. It also gives the opportunity to practically use brand-new, previously unknown possibilities of communication technologies.

Most of the students and teachers were ready to switch to the distance mode of learning because they had taken lectures online before. However, studies confirm that some teachers did not have real practice and experience in online learning (Aroshidze & Dzagania, 2021; Şahin, 2021). Students and teachers were forced to master new methods and technologies (ZOOM, Teams, Skype), as well as video conferencing, screen sharing, and various technical skills.

The majority of students and teachers preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods as it takes into account the specifics of particular subjects and the students' own choices. This kind of choice allows those who prefer to get an education remotely to choose an online course, and students who learn better only through direct communication to choose auditory training. In this regard, it is necessary to equip university auditoriums with the necessary technical capabilities and to develop curricula that will allow students to decide whether to attend the lecture in the auditorium or to join online. The synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods is a rather complex problem and requires further research.

Even though the transition to distance learning has undoubtedly proved to be an effective tool in protecting oneself from the COVID-pandemic, there are many drawbacks. This could be caused by limited distance learning communication, technical difficulties, and an uncomfortable environment. The most problematic for students was the comfortable workplace needed for distance learning. According to the teachers, the biggest obstacle in online teaching was the weak technical capabilities of the equipment used by the students or its complete absence.

According to the survey results, access to the internet was problematic for some of the surveyed students (15.6%, n = 63). It was primarily related to the low quality and malfunction of the internet in several regions (villages) of Georgia and, because of that, students were not able to participate in both lecture and practical classes. All these reasons discussed above led to a low level of students’ knowledge. It is also noteworthy that some of the students from rural districts had an opportunity to save on costs associated with renting an apartment. However, online tuition became a serious challenge for them as they faced the problem of accessing the internet.

Studies show that in some cases, due to the lack of experience of working in distance learning mode, too much time in the beginning was spent on the technical organisation of the lecture (entering the platform, turning on the microphone, adjusting the camera, etc.), which negatively affected the quality of online lectures (Roszak et al., 2021).

One of the serious problems for teachers is the form of students’ involvement (they have the right to "cover" their faces). The students have the right not to turn on the video camera, or "cover" their face, which excludes visual contact and disrupts the process of exchanging knowledge. Consequently, it is difficult for the teacher to understand how well the students perceived the explained lecture. However, while turning off the video eye, students can easily be distracted by various activities and they may not concentrate on the lecture material. Students find the process of learning with a computer screen boring and they are less motivated to participate in lectures.

Research has shown that the majority of students and teachers think that the online distance learning regime has a negative impact on the quality of learning. In this regard, the test methodology for assessing student knowledge is particularly problematic. Closed-ended testing is sometimes used to test students’ knowledge, accompanied by a few possible answers. This kind of exam tests students’ memory more than their knowledge and excludes students’ critical thinking and reasoning skills.

Other research also shows that students do not find online lessons as effective as traditional teaching methods (Nepal et al., 2020; Abbasi et al., 2020). Students who are in favor of online learning, however, believe that it reduces their use of vehicles and the cost of attending auditorium lessons. In addition, while online lectures can be recorded, independent learning is much more significant.

The study also included non-Georgian students and the vast majority of them preferred the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods. Apart from the academic point of view, this may also be related to their socialisation, as in most cases non-Georgian students are not permanent residents of Georgia and their only source of socialisation is the university. Consequently, during the distance learning mode, they lose their only place for making new friends. Usually, the time spent at the university for students is memorable and impressive. At the same time, students had direct contact with lecturers during conventional studies, not only in the auditoriums but also in the university library, cafes, and various university events, where useful information can be shared.

Other studies also confirm that students' social interactions and relationships have become increasingly complex during distance learning (Leal et al., 2021). Most students and teachers have access to all the necessary technical equipment needed for distance learning (computer, personal computer, tablet, mobile phone, etc.). They have the freedom to choose the most convenient learning platform. Students and teachers mainly use Moodle's platform for online learning mode. However, some students are involved in the learning process through mobile phones and apply to platforms such as WhatsApp, Skype, etc. (Yilmaz, 2016). Mobile devices are simple and comfortable to use and they are becoming ever more popular. However, in some cases, the use of mobile phones was associated with the lack of computers and, because of that, students were not able to complete tasks on time, so they had to write homework by hand, then take a picture of it and send it in by e-mail. It should also be highlighted that some students were not properly skilled in computer technology.

The technological progress of the 21st century has had a great impact on the process of education. the crisis caused by the COVID-19 epidemic has identified the need to advance the methods of continuous, high-quality acquisition of knowledge. To protect education from the pandemic, an online teaching model was introduced, which resulted in a serious challenge to both the student and the teacher.

The study found the following aspects of students’ and teachers’ satisfaction with online learning: more free time, reduced travel costs, and technical support availability and flexibility. Online learning helps students acquire the skills needed to work independently, enhance self-organisation skills, communicate effectively with computer technology, and make responsible decisions independently. Most of the students and teachers prefer the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods.

When teaching online, it is necessary to turn students from passive beneficiaries to involved students through interactive sessions, presentations and open discussions. It is preferable to equip university auditoriums with the necessary technical capabilities and to develop curricula that allow the synthesis of distance and auditory learning methods.

Further research on the development of online learning is needed. Universities might take the opportunity to identify shortages, to share the experience on the global level and to encourage more transnational cooperation in order to increase the quality of global education, with the aim of constructing a worldwide online education network.

Abbasi, S., Ayoob, T., Malik, A., & Memon, S.I. (2020). Perceptions of students regarding e‑learning during COVID‑19 at a private medical college. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 36(COVID19-S4),S57-S61. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2766

Adresi, Y. (2020). Investigation of students’ attitudes towards applied distance education in the covid-19 pandemic process in higher education institutions: Example of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Department. Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Health Sciences Journal, 3(1), 1-6.

Aker, S., & Mıdık, Ö. (2020). The views of medical faculty students in Turkey concerning the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Community Health, 45(4), 684–688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00841-9

Aroshidze, M., & Dzagania, I. (2021). Pros and cons of online learning. International Scientific Conference Online Learning Under the Conditions of Covid-19 and Educational System. Academy of Educational Sciences of Georgia.

Berawi, M. A. (2020). Empowering healthcare, economic, and social resilience during global pandemic Covid-19. International Journal of Technology, 11(3), 436–439. doi: https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v11i3.4200

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Cheng, Y. M. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of e-learning acceptance. InformationSystems Journal, 21(3), 269-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.2010.00356.x

Cucinotta, D., & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 15 (7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fawaz, M., & Samaha, A. (2021). E‐learning: Depression, anxiety, and stress symptomatology among Lebanese university students during COVID‐19 quarantine. Nursing Forum, 56(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12521

Kamarianos, I., Adamopoulou, A., Lambropoulos, H., & Stamelos, G. (2020). Towards an understanding of university students’ response in times of pandemic crisis (COVID-19). European Journal of Education Studies, 7(7), 20-40. doi:10.46827/ejes.v7i7.3149

Kaparounaki, C. K., Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D. P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V., Papadopoulou, K. K., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111

Katić, S., Ferraro, F. V., Ambra, F. I., & Iavarone, M. L. (2021). Distance Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. A comparison between European countries. Education Sciences, 11(10), 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11100595

Leal, Filho., W., Wall, T., Rayman-Bacchus, L. Mifsud, M., Pritchard, D. J., Lovren, V. O., Farinha, C., Petrovic, D. S., & Balogun, A. L. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11040-z

Leszczyński, P., Charuta, A., Łaziuk, B., Gałązkowski, R., Wejnarski, A., Roszak, M., & Kołodziejczak, B. (2018). Multimedia and interactivity in distance learning of resuscitation guidelines: A randomised controlled trial. Interactive LearningEnvironments, 26(2), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2017.1337035

Iyer, P., Aziz, K., & Ojcius, D.M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. Journal of Dental Education, 84(6), 718-722. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12163

Molotsi, A. R. (2020). The university staff experience of using a virtual learning environment as a platform for e-learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Online learning, 3(2), 133-151. https://doi.org/10.31681/jetol.690917

Nepal, S., Atreya, A., Menezes, R. G., & Joshi, R. R. (2020). Students’ perspective on online medical education amidst the COVID‑19 pandemic in Nepal. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council, 18(3), 551‑5. https://doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.v18i3.2851

Othman, N., Ahmad, F., Morr, C. E., & Ritvo, P. (2019). Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety and stress: a survey with university students. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0275-x

Owusu-Fordjour, C., Koomson, C.K., & Hanson, D. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on learning. The perspective of the Ghanaian student. European Journal of Educational Studies, 7(3), 88-101. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3753586

Pan, H. (2020). A glimpse of university students’ family life amidst the COVID-19 virus. Journal of Loss Trauma, 25(6-7), 594-597. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1750194

Pelikan, E. R., Korlat, S., Reiter, J., Holzer, J., Mayerhofer, M., Schober, B., … & Lüftenegger, M. (2021). Distance learning in higher education during COVID-19: The role of basic psychological needs and intrinsic motivation for persistence and procrastination–a multi-country study. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0257346. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257346

Perz, C. A., Lang, B. A., & Harrington, R. (2020). Validation of the fear of COVID-19 scale in a US college sample. International Journal of Mental Health Addictions, 20, 273-283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00356-3

Rahman, A. (2021). Using students’ experience to derive effectiveness of COVID-19-lockdown-induced emergency online learning at undergraduate level: Evidence from Assam, India. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 71-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/23476311209805

Reznik, A., Gritsenko, V., Konstantinov, V., Khamenka, N., & Isralowitz, R. (2020). COVID-19 fear in Eastern Europe: Validationof the fear of COVID-19 scale. International Journal of Mental Health Addictions, 19(5), 1903-1908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00283-3

Rienties, B., Giesbers, B., Lygo-Baker, S., Ma, H. W. S., & Rees, R. (2016). Why some teachers easily learn to use a new virtual learning environment: A technology acceptance perspective. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(3), 539-552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.881394

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA, 323(21), 2131-2132. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Roszak, M., Sawik, B., Stańdo, J., & Baum, E. (2021). E-learning as a factor optimizing the amount of work time devoted to preparing an exam for medical program students during the COVID-19 epidemic situation. Healthcare, 9(9), 1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9091147

Şahin, M. (2021). Opinions of university students on effects of distance learning in Turkey during Covid-19 pandemics. African Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 526-543. doi:10.30918/AERJ.92.21.082.

Stratton, S. J. (2021). Population research: convenience sampling strategies. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36, 373-374. doi:10.1017/S1049023X21000649

Verma, A., Verma, S., Garg, P., & Godara, R. (2020). Online teaching during COVID-19: perception of medical undergraduate students. Indian Journal of Surgery, 82(3), 299-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-020-02487-2

Yilmaz, O. (2016). E‑learning: Students input for using mobile devices in science instructional settings. Edu Learn, 5(3), 182‑92. doi:10.5539/jel.v5n3p182

World Health Organization. (2022). Worldometer COVID-19 Data.

Authors:

Tengiz Verulava is a professor at Caucasus University and director of the Health Policy and Insurance Institute. He holds a PhD in Medical Sciences. He has over 25 years of experience on European Union and National (Georgia) funded projects. His research portfolio includes 16 books and over 300 journal papers in international peer-reviewed scientific journals. He is a Chief Editor of the scientific journal Health Policy, Economics, and Sociology. Dr. Verulava was awarded the Order of Best Scientist by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation (2018) and for the best scientific paper by the Association of Security Researchers Science for Sustainable Development and Security (2021). Dr. Verulava is an Honorary Research Fellow of School of Psychology and Public Health at La Trobe University (Melbourne, Australia) and is active in organising annual scientific conferences on Health Policy, Economics, and Sociology. His research interests are focused on Public Health, Health Economics, Health Sociology, Global Health, Managed Care, Primary Health Care, Insurance, and Universal Health Care. Email: tverulava@cu.edu.ge

Kakha Shengelia is a president of Caucasus University. He holds an MA from Tbilisi State University; an MBA degree in Management from the University of Hartford (Hartford, USA) and a PhD from Georgian Technical University (Georgia). Dr. Shengelia was a Member of Parliament of Georgia, Deputy Chairman of Committee of Education, Science, Sport and Culture and Committee of Foreign Affairs. He was a Vice-Mayor of Tbilisi in Social Affairs and is a President-elect of the IAUP (International Association of University Presidents). Dr. Shengelia was awarded the Presidential Order of Excellence by the President of Georgia and the Ring of Honor by the University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria. Dr. Shengelia is an Honorable Doctor of Tallinn University of Technology and a member of the Steering Committee of NISPAcee (The Network of Institutes and Schools of Public Administration in Central and Eastern Europe). Dr. Shengelia was conferred the title of Honorary Doctor of Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara. Email: kshengelia@cu.edu.ge

Giorgi Makharashvili is a professor at Caucasus University and a Dean of the School Medicine and Healthcare Management. He holds an MD degree from Tbilisi State University. Email: gmakharashvili@cu.edu.ge

Cite this paper as: Verulava, T., Shengelia, K., & Makharashvili, G. (2023). Challenges of distance learning at universities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Georgia. Journal of Learning for Development, 10(1), 75-90.