2022 VOL. 9, No. 1

Abstract: The scores obtained by students in examinations where internet access was allowed during the examination were compared with the scores obtained in traditional examinations where no assistance was allowed. These scores were then compared with those obtained in a standardised school examination on the same topic or subject, taken by the same students a year before. We observed that scores dropped by over 70% within a year of taking a traditional examination but could be significantly improved if internet access is allowed in the later examination. We further observed that scores in examinations where internet access was allowed were consistently higher than where internet access was not allowed. Finally, we report an analysis by rank and observe that student rankings change both over time and whether internet access was allowed or not. This leads us to suggest that use of the internet during examinations measures abilities that are different and more meaningful to our times than those that are measured by traditional examinations based on memorisation and unassisted recall.

Keywords: assessment, examination, cheating, internet access, memory.

Use of the internet is not allowed during traditional examinations (TE) in most educational institutions in the world. Also not allowed during TE are books or notes in any form, talking or looking at the work of other examinees. All such methods that may be of assistance to an examinee during a TE are generally classified as “cheating” (Colnerud & Rosander, 2009) and are forbidden. These restrictions are put on an examinee because the purpose of an educational examination is to measure the knowledge an examinee has in the subject in which he or she is being examined. The words “knowledge” and “knowing” are circularly defined in most dictionaries. For example, in the Merriam Webster Dictionary, “knowledge” is defined as “The fact or condition of knowing something….” , while “knowing” is defined as “Having or reflecting knowledge….”. Similar circular definitions are present in the Cambridge and other dictionaries. Since these words are hard to define, it would be more precise to assume that a traditional examination measures an examinee’s ability to memorise, recall without assistance, and apply recalled memories to answer questions (which is considered good, see, for example, Persky & Fuller, 2021). This would explain why all assistive methods are forbidden during traditional examinations.

Outside of educational examinations, extensive use of the internet and all other assistive methods including asking others and looking at what others are doing, are not only allowed but actively encouraged in the hope that a correct answer or solution will be found to a question or problem (Apuke & Iyendo, 2018). The ability to answer a question or solve a problem quickly and accurately using any available resource is considered a desirable skill. This is opposite to what educational examinations (TE) attempt to measure. These diametrically opposite points of view are possibly a result of the origins of the TE from a time when it was important to prepare students to solve problems without any assistance whatsoever. A time when books, libraries, teachers, and even helpful friends, could not be made instantly available at the time of need. The existence of the internet and tiny devices that can access the internet at high speeds have changed the need for many skills that were vital in the 20th and prior centuries (van Laar et al., 2020). The changes have been too rapid for most educational systems to adapt.

In order to make changes in how or what educational examinations should measure, we first need to know the effects that assistive technology would have on TE, if they were allowed. In this paper we report the results of an experiment to measure the effects of allowing internet access during traditional examinations. For the sake of brevity, we will name examinations where internet access is allowed as Internet Assisted Examination (IAE).

If internet access is allowed during an examination:

We have used the standard experimental research model where single variables are manipulated while others act as controls.

Table 1: Profiles of Alpha and Beta sample groups

| Group | Alpha |

Beta |

Men |

13 |

15 |

Women |

9 |

7 |

Average age |

17.7 years |

17.8 years |

Standard deviation |

0.6 years |

0.6 years |

Table 2: Examination schedules and average percentage scores for Geography and History examinations with standard deviations in brackets

Exam G |

Day 0 |

|

Day 28 |

|

Day 66 |

|

Day 77 |

|

IAE-TE |

|

TE |

IAE |

TE |

IAE |

TE |

IAE |

TE |

IAE |

|

Alpha |

14.06 (4.92) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

71.75 (13.14) |

57.7 |

Beta |

|

83.90 (7.35) |

|

|

|

|

35.55 |

|

58.2 |

Exam H |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alpha |

|

|

|

73.27 (14.45) |

22.76 (11.78) |

|

|

|

50.5 |

Beta |

|

|

7.10 (5.51 |

|

|

73.35 (16.25) |

|

|

66.2 |

Table 3: Scores obtained by the participants in their school final examination in the Geography-History paper

| Group | Average Score |

SD |

Alpha |

89.10 |

7.68 |

Beta |

90.59 |

8.75 |

Both combined |

89.76 |

8.10 |

While we carried out a number of analyses on the data obtained, for the purpose of this paper, we decided to describe only those that showed clear results requiring little statistical interpretation:

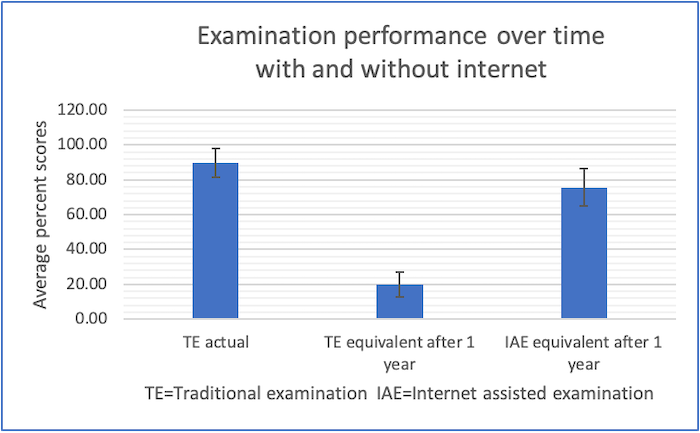

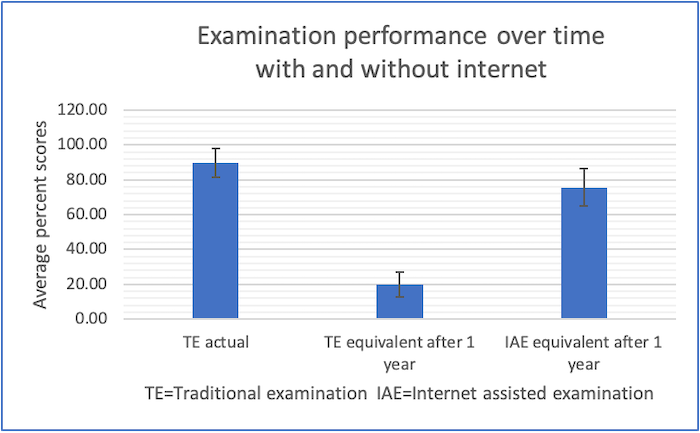

Figure 1: Mean scores with standard deviations in the actual school-leaving examination

compared to scores in equivalent TE and IAE after one year

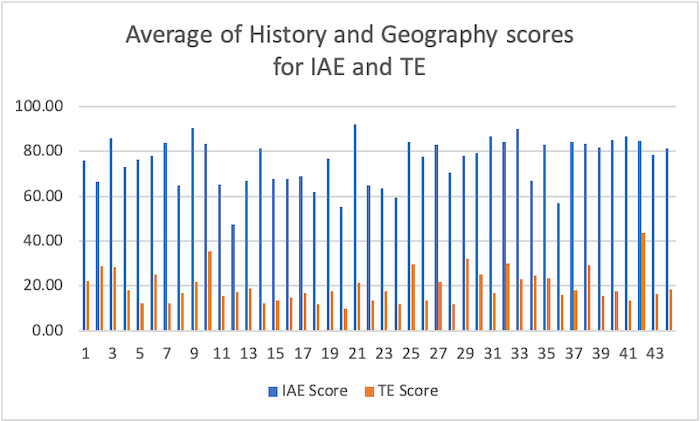

Figure 2: Average of the scores in Geography and History for all the participants

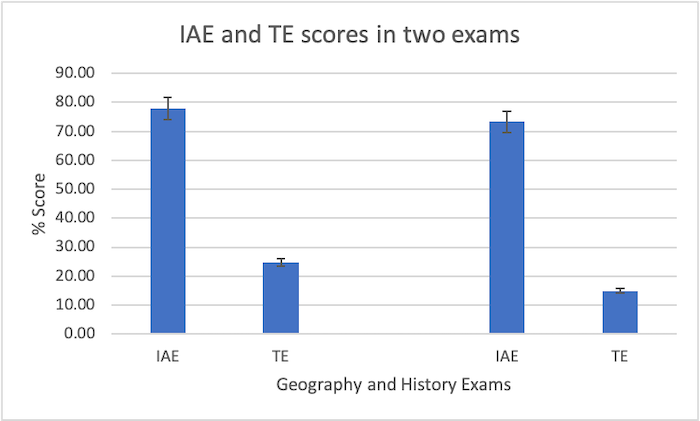

Figure 3: Mean scores in Geography and History with and without internet access

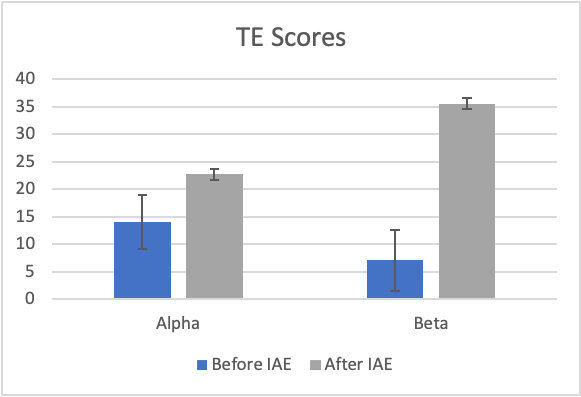

Figure 4: TE scores when administered before and after IAE

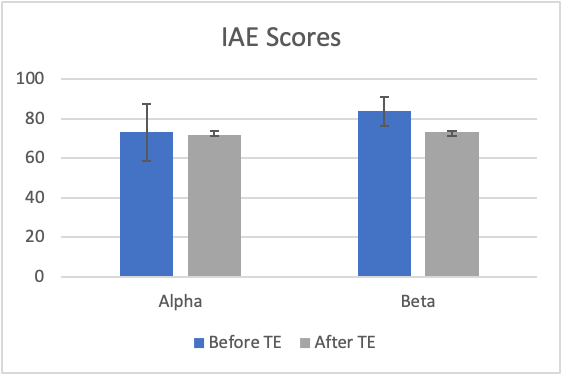

On the other hand, when IAE are administered after TE, we did not notice any significant difference. This is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: IAE scores when administered before and after TE

Curiously, when the IAE was administered after the TE, we observed a small drop in the IAE scores. It is possible that the earlier memorised knowledge from TE prevented effective use of the internet during IAE, however, this is speculative and needs more experimentation to establish.

The sample size in this study was not large and the findings cannot, therefore, be generalised. A study with a larger sample is suggested. However, we do get a fascinating glimpse into the effects of internet access on examinations. The ability to compute (search), comprehend and communicate may lie at the heart of educational assessment for the generation growing up in the 21st century.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author Contributions: The first author provided the design and analysis for this study. The second author developed the methods, conducted the experiments and collected the data.

Funding: This study was not funded by any research grant.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the participants who found the study of great interest, volunteered their time and cooperated at every stage of the experiments.

Apuke, O. D., & Iyendo, T. O. (2018). University students' usage of the internet resources for research and learning: Forms of access and perceptions of utility. Heliyon, 4(12), e01052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e01052

Colnerud, G., & Rosander, M. (2009). Academic dishonesty, ethical norms and learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(5), 505-517.

Persky, A. M., & Fuller, K. A. (2021, July). Students’ collective memory to recall an examination. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 8638. doi:https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe8638

van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M. & de Haan, J. (2020). Determinants of 21st-century skills and 21st-century digital skills for workers: A systematic literature review. Sage Open, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019900176

Authors:

Sugata Mitra retired in 2019 as Professor of Educational Technology at Newcastle University in England, after 13 years there, including a year in 2012 as Visiting Professor at MIT MediaLab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. He is Professor Emeritus at NIIT University, Rajasthan, India.

His work on children’s education include the ‘hole in the wall’ experiment where children access the internet in unsupervised groups, the idea of Self Organised Learning Environments (SOLEs) in schools, the role of experienced educators over the internet in a ‘Granny Cloud’ and the School in the Cloud where children take charge of their learning – anywhere. Email: sugata.mitra@niituniversity.in

Dr Ritu Dangwal is an Assistant Professor at NIIT University in India. She has a PhD in Organisational Psychology and an active research record spanning over 20 years. Her interests include children's education, self organised learning, open and distance education, psychology and assessment. Email: Ritu.dangwal@niituniversity.in

Cite this paper as: Mitra, S., & Dangwal, R. (2022). Effects of internet access during examinations. Journal of Learning for Development, 9(1), 129-136.