2021 VOL. 8, No. 2

Abstract: This article offers a global overview of the burgeoning field of micro-credentials and their relationship to lifelong learning, employability and new models of digital education. Although there is no globally accepted definition of micro-credentials, the term indicates smaller units of study, which are usually shorter than traditional forms of accredited learning and courses leading to conventional qualifications such as degrees. The paper aims to provide educators with a helicopter view of the rapidly evolving global micro-credential landscape, with particular relevance to higher education leaders, industry stakeholders and government policy-makers. It addresses five questions: (i) What are micro-credentials? (ii) Why micro-credentials? (iii) Who are the key stakeholders? (iv) What is happening globally? and (v) What are some of the key takeaways? Drawing on a European-wide perspective and recent developments in The Republic of Ireland, the paper concludes that micro-credentials are likely to become a more established and mature feature of the 21st-century credential ecology over the next five years. While the global micro-credential landscape is currently disconnected across national boundaries, more clarity and coherence will emerge as governments around the world increasingly align new credentialing developments with existing national qualification frameworks. The micro-credentialing movement also provides opportunities for governments and higher education institutions in partnership with industry to harness new digital learning models beyond the pandemic.

Keywords: credentials, micro-credentials, digital badges, employability, transversal skills.

Micro-credentials are gaining increasing momentum around the globe. A growing interest in micro-credentials and short learning experiences has accelerated since the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic, as governments look to get people back to work, endeavour to create new jobs in areas of growth and address specific skills gaps. This paper set against this challenging backdrop offers a global helicopter overview of the burgeoning field of micro-credentials. It is also framed around the increasing significance of new digital education models more generally. We begin by acknowledging that the current micro-credential landscape is messy and poorly defined, with many competing viewpoints and disconnected initiatives. Nevertheless, some common underlying drivers can be identified as increasingly people raise questions about the relevance and fit for purpose nature of traditional qualifications for preparing learners for today’s rapidly changing digital society. Several examples of micro-credentialing initiatives worldwide are reported as different stakeholders and interest groups explore their potential for upskilling, responding to the changing nature of work and providing new pathways for lifelong learning. Finally, the paper looks to the future. We conclude that the micro-credentialing movement is not just another passing educational fad. Increasingly, leading universities, quality assurance agencies, and government policy-makers are giving more serious attention to new recognition frameworks and digital models of higher education.

There is no global consensus on the term ‘micro-credential’. According to Kazin and Clerkin, (2018, p. 3), this situation is partly because the field is still “rapidly evolving” and subject to constant change. To confuse matters and make the nomenclature even messier, several other terms are commonly used instead of, or interchangeably with, the term micro-credential—for example, digital badges, online certificates, alternative credentials, nano-degrees, micro-masters, and so on. Hence, internationally the definition of micro-credentials varies significantly depending on who is using the term and in what context. Rossiter and Tynan (2019, p. 2) report the absence of a clear definition of micro-credentials “…can make it confusing and bewildering to navigate…” the field.

As a result, the term ‘micro-credential’ has been used to describe all manner of shorter forms of learning experiences—irrespective of type, size or delivery mode. For example, Pickard, Shah and De Simone (2018) widely define a micro-credential as “any credential that covers more than a single course but is less than a full degree” (p. 17). Oliver (2019, p. 1), formerly from Deakin University in Australia, proposes the definition of a “certification of assessed learning that is additional, alternate, complementary to, or a formal component of a formal qualification”. Importantly, Oliver (2019) emphasises verified learning outcomes and a micro-credential’s relation to traditional formal qualifications such as a bachelor’s or master’s degree (i.e., macro-credentials).

An emerging definition of micro-credentials from a European project, MicroHE, is where a micro-credential is viewed as a “sub-unit of a credential or credentials that confer a minimum of 5 ECTS, and could accumulate into a larger credential or be part of a portfolio” (MicroHE Consortium, 2020). This definition, which refers to study credits based on the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS), begins to narrow down the criteria for a micro-credential in terms of workload and hours of learning. The New Zealand Qualifications Authority (2019) goes further and bounds a lower and upper limit, defining micro-credentials as between five to 40 credits in size. However, the definition of credit value and how this relates to macro-credentials varies across regions and countries, further complicating attempts at reaching an agreed definition.

A common point of confusion and contention is the relationship between the terms ‘micro-credential’ and ‘digital badge’. As Sturgis (2019) states, “the difference between micro-credentials and badges... was becoming less and less clear... Not that it was ever that clear in the first place”. Moreover, the traditional academy often views the term ‘badge’ with suspicion as they perceive them as eroding the status, credibility and reputation of conventional qualifications. Also, it is important to note that the term ‘micro-credential’ has become synonymous with certificates of assessed learning earned through the major MOOC platforms, with many providers adopting their own labels: MicroMasters (EdX), Nanodegree (Udacity) and Specialisation (Coursera)

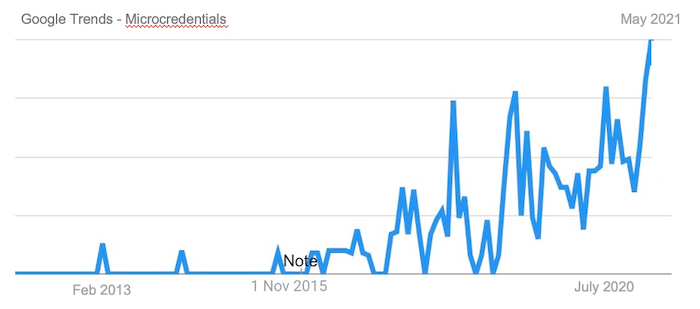

A Google Trends analysis conducted in June 2021 revealed that the term ‘microcredentials’ first appeared in Google search results in 2013. Figure 1 shows that the highest point in the trend data for the term ‘microcredentials’ was in May 2021. The term is most searched in Australia but also appears frequently among search queries in Malaysia, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom in that order. Currently, there are not enough search queries from other countries to report any trends, but readers may wish to compare these findings with those available using related search terms.

Figure 1: Google Trends data on Micro-credentials

Table 1 presents the global Google Trends results for the term ‘micro-credentials’ and its variants. The results of this comparison show that the term ‘micro-credential’ using a hyphen is a less frequently searched term and presents a different view of global trends data but that many of the terms were in use over 15 years ago. This finding echoes Oliver’s (2019, p. i) assertion that the concept of micro-credentials is not a new one, “…for decades, extension courses have enabled further education, community engagement and lifelong learning”. Furthermore, the search queries related to each term demonstrate that terms can be linked to the platform that provides this type of micro-credential (e.g., EdX for micromasters), or a specific course that uses the term in its title (e.g., android basics nanodegree program). Notably, the digital badges provided by IBM appear as a popular search query related to the term ‘digital badge’.

Table 1: Google Trends Comparison

Term |

First Appeared |

Top Five Search Locations |

Recent Related Queries |

Microcredentials |

2013 |

Australia |

No data available |

Micro-credential |

2015 |

United States |

No data available |

Digital Badge |

Before 2004 |

United Kingdom |

Digital technology merit badge |

Short Online Course |

Before 2004 |

South Africa, |

Free online courses |

Nanodegree |

2006, popularised 2014 |

Egypt |

Udacity |

Micromasters |

Before 2004 |

Singapore |

Micromasters MIT |

Alternative Credential |

2004 |

United States |

No data available |

Digital Credential |

Before 2004 |

United States |

Digital Badge |

A UNESCO report makes the point that the term ‘micro-credential’ is an umbrella term that “encompasses various forms of credential, including ‘nano-degrees’, ‘micro-masters credentials’, ‘certificates’, ‘badges’, ‘licences’ and ‘endorsements’” (UNESCO, 2018, p.10). On the other hand, Beirne, Nic Giolla Mhichil and Brown (2020) point out that the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE) (2019) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have adopted variants of the term ‘alternative credentials’, which encompasses but also differentiates between academic certificates, professional certificates, digital badges and micro-credentials (Kato, Galán-Muros, & Weko, 2020; ICDE, 2019). This subtle but important distinction indicates there is an underlying tension between promoting alternative credentials in parallel to existing awards as opposed to fully coherently embedding the adoption of micro-credentials into existing qualification frameworks.

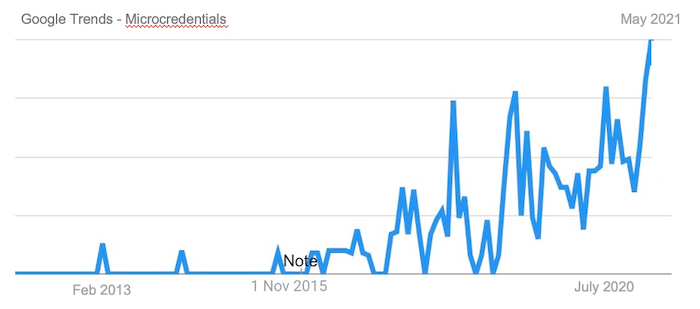

To help reconcile this tension and more clearly depict the field, Brown, Nic Giolla Mhichíl, Beirne and Mac Lochlainn (2020) developed a chart to help map the new and emerging credential landscape. An updated version of this chart shown in Figure 2 depicts four credential quadrants across two axes:

At one end of the y-axis, traditional macro-credentials and credit-bearing micro-credentials are positioned, which are attained through formal and semi-formal study. On the x-axis, the degree to which credentials and related units of study are bundled together by the awarding body or institution is depicted, as opposed to where learners have a high degree of choice over how they wish to make up their own learning bundle. According to this typology, micro-credentials are differentiated from traditional macro-credentials, non-status awards such as short courses and nano-credentials, including digital badges or certificates, as unbundled, credit-bearing, stackable credentials.

However, the distinction between quadrants in this credential map is not always as clear-cut in reality. For instance, an individual learner could have a non-credit-bearing badge in project management. This badge could be assessed as recognition of prior learning (RPL) by a university or as part of a wider professional portfolio, which, in turn, contributes to a credit-bearing micro-credential.

Figure 2: The new credential ecology

Source: Brown et al, 2020

Another way of expressing the different types of micro-credentials and related pathways is to visualise three distinct categories. Each category can be represented on a different axis. For example, the y-axis depicts an upward, life-long, career-focused trajectory where different learning blocks can be stacked together to earn a credit-bearing micro-credential. This vertical “stackable” representation contrasts with the x-axis which encapsulates non-formal and informal short learning experiences with more of a sideways, life-wide, interest-focused trajectory. Such horizontal learning is typically non-stackable and contributes to non-credit-bearing micro-credentials that may or may not relate to one’s work or employability. The micro-credentials by RPL or portfolio example presented above can be depicted as a diagonal line that joins or connects both axes as people reflect on a collection of small informal and non-formal learning experiences completed over time. Of course, such a learning portfolio needs to be formally assessed against transparent criteria. This third category shows that the vertical and horizontal depiction of micro-credential types is not binary or mutually exclusive.

Importantly, clarifying what is meant by a micro-credential is critical in addressing questions such as, “Credentialed to do what?” or “How does it compare to a formal university-level degree?”. The question of how small, specifically, a typical micro-credential might be, how it might be expressed, in addition to how it relates to the above mentioned unbundling movement within higher education, has been an open one. At the same time, the core questions as to how such credentials might be implemented has also been discussed in some detail (Chakroun & Keevy, 2018). This discussion was very much the focus of a special European Commission Consultation Group that, throughout 2020, was charged with developing a European-wide approach to micro-credentials (see Shapiro, 2020). Shapiro (2020, p. 5) observed that “The lack of a shared definition is currently perceived as the most substantial barrier to further development and uptake of micro-credentials” in the European Union.

The varying definitions and synonyms for the term ‘micro-credential’ have also created confusion and a lack of understanding amongst employers and potential employees. A recent study, for example, which interviewed key micro-credential stakeholders (students, educational institutions, governments and employers) across Europe, found that the majority of participants did not know what the term meant (Micro-HE Consortium, 2019). Another group of interviews conducted by Resei, Friedl, Staubitz and Rohloff (2019) also found that employers and even universities (directors and strategy planners) were unaware of the term, resulting in low awareness of the value associated with this new type of credential. It follows that agreeing on what is meant by the term ‘micro-credential’ is essential to establish standards, compare best practices, and ensure recognition and mobility for credential bearers and issuers.

To this end, the above mentioned European Commission Consultation Group has produced the following definition:

A micro-credential is a proof of the learning outcomes that a learner has acquired after a short learning experience. These learning outcomes have been assessed against transparent standards (European Commission, 2020a, p. 10).

This definition makes it explicit that a micro-credential is a documented statement awarded by a trusted body to signify that a learner upon assessment has achieved learning outcomes of a small volume of learning against given standards and in compliance with agreed-upon quality assurance principles. Implicit in this current definition is that ideally, micro-credentials should be referenced to, or embedded within, national qualification frameworks and the European Qualification Framework (EQF). While a recent survey, as part of the MICROBOL project, showed that most European countries (n = 22) had implemented policies related to micro-credentials (Lantero, Finocchietti & Petrucci, 2021), Ireland is relatively unique for having an existing mechanism for recognising them. Notably, the National Framework of Qualifications (NFQ) in Ireland already accommodates special purpose awards, which enable credit-bearing micro-credentials to stack towards larger macro-credentials.

In February 2020, using this NQF provision along with the Common Micro-credential Framework (CMF) developed by the European MOOC Consortium (2019), Dublin City University (DCU) launched the first European credit-bearing, stackable, fully online micro-credential offered through the FutureLearn platform. Importantly, this micro-credential in the burgeoning area of FinTech, which explores technological innovation in the financial services industry, has full status as a DCU award under the university's qualification framework. The first-course offering attracted online students from around the globe. DCU is currently developing a wider suite of micro-credential offerings in key growth areas in partnership with FutureLearn and the new ECIU University. The latter is widely recognised as one of the leading European university consortia with ambitious plans and a clear roadmap for developing micro-credentials (Brown, et al, 2021). This pioneering DCU example shows growing convergence on a global and European stage between MOOC platforms, international partnerships, and the micro-credentialing movement, a point further illustrated in the following section.

Governments worldwide are endeavouring to respond to the changing nature of work and growing skills gaps in response to what is being called Industry 4.0 or theFourth Industrial Revolution. Other disruptive change forces such as increasing globalisation, ageing populations, climate change and technological advancements, including the increasing impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI), underscore the importance of upskilling, reskilling and developing the capacity to thrive in new digital world. We live in uncertain and rapidly changing times that create new job opportunities and bring with them risks of displacement and an urgent need for re-skilling among workers (Manyika et al, 2017; Deloitte Insights, 2019; OECD 2020). It is predicted by the World Economic Forum (2020) that 50% of all employees will need reskilling by 2025 as the “double-disruption” of the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing automation transforming jobs takes hold.

In a similar vein, a 2017 report published by the McKinsey Global Institute claims that by 2030, 75 million to 375 million workers (3% to 14% of the global workforce) will need to switch occupational categories (Manyika et al, 2017). The Institute for the Future (2017) goes further in a report which says “…that around 85% of the jobs that today’s learners will be doing in 2030 haven’t been invented yet” (p. 14). Although we can debate the accuracy of such predictions, it is widely accepted that new technologies will reshape millions of jobs over the next decade. As the skill demands continue to change, people will continually need to re-train, reskill or redeploy to avoid redundancy and social and economic displacement in their local communities.

It follows that new types of training and higher education will be needed to facilitate reskilling and up-skilling. Traditional educational degrees, which are being increasingly criticised for their high cost, especially in the United States, lack of alignment with employment needs, and inability to adapt in a timely manner to changing trends, are no longer the only answer. Arguably, the traditional university degree no longer offers the same job security or helps to future-proof your career. People increasingly need flexible, personalised and on-demand life-long and life-wide learning that equips them with the transversal skills and knowledge to adapt to life and work in an evolving digital society (OECD, 2019). Thus, despite limited evidence tracking longer-term impact, micro-credentials are being taunted as potentially cheaper and more flexible opportunities for people to gain traditional macro-credentials (Boud & Jorre de St Jorre, 2021).

Notably, some high-profile international companies such as EY, Google and IBM have even adopted a recruitment strategy that gives people a foot in the door based on non-traditional education and soft skills like grit, tenacity and perseverance. Google has explicitly stated that it wishes to disrupt established education models through short courses credentialed by itself. They will recognise these courses as the equivalent of a full bachelor’s degree for recruitment selection purposes (Bariso, 2020). The previous Trump administration in the United States signed an executive order in 2020, emphasising skills rather than degrees in federal hiring. There is a growing assumption—albeit unproven—that “skills, rather than occupations or qualifications, form the job currency of the future” (Deloitte, 2019, p. 19).

This trend suggests that the current credential system developed in the 19th century and the traditional “bricks-and-mortar” approach to educational provision is no longer fit for purpose. Indeed, it will be almost impossible to meet the projected growing demand for higher education worldwide through traditional delivery models. Some argue for major system-wide disruption and the radical unbundling of traditional degrees to better recognise nano talents and bite-sized blocks of learning more relevant to the needs of society and changing nature of work (Craig, 2015). Ultimately, beyond our response to the current COVID crisis, there is a general understanding that countries will benefit from greater investments in life-long learning, which help close skills gaps and embrace the potential of new digital models of training and higher education.

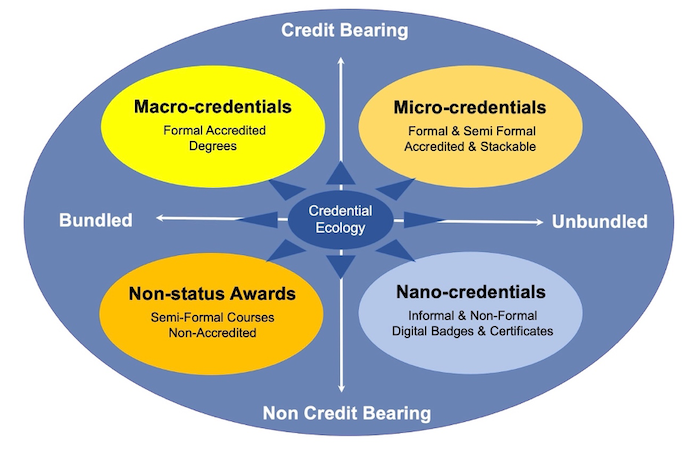

Figure 3: European rate of participation in lifelong learning

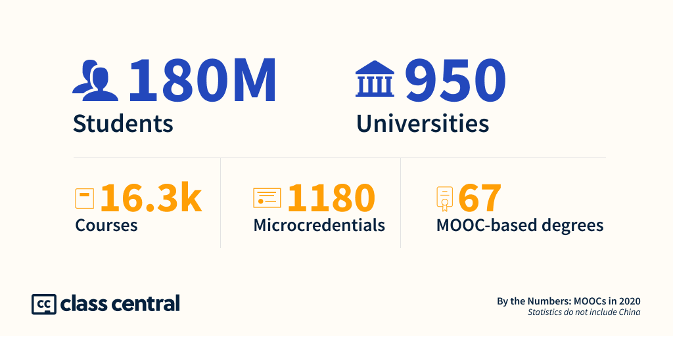

The current reality in Europe is that the rate of participation in lifelong learning remains very low, as illustrated in Figure 3 (Eurostat, 2020). However, even before the COVID-19 crisis, demand for new lifelong learning pathways and alternative forms of online higher education was rapidly increasing. Notably, personalised learning, micro-learning and high-velocity training were amongst the key global education trends identified by Euromonitor (2017). As illustrated in Figure 4, it is also noteworthy that by the end of 2020, more than 180 million learners enrolled in over 16,000 MOOCs throughout the world, with around 1200 micro-credentials (Shah, 2020a). Importantly, this figure is not fully inclusive of MOOCs available through Chinese or Indian platforms. Characterised as flexible, open, self-paced, highly interactive, interdisciplinary and cost-reducing, MOOCs are becoming increasingly accepted and established in both higher education and industry. While many governments have been slow to respond to the MOOC movement, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased learner engagement. For example, in June 2020, there were almost 500 million visits to the major platforms around the world (HolonIQ, 2020). ClassCentral has also reported that the numbers of sessions on the major MOOC platforms during March and April 2020 were up 50% to 400% over previous years (Shah, 2020b). The key point is that more and more learners are looking for alternative education solutions and ways of upskilling in response to a rapidly evolving digital world.

Figure 4: Growth of MOOCs in 2020

Accordingly, there is increasing interest from industry, policy-makers and educational stakeholders in the value of micro-credentials to enable learners to attain more personalised micro versions of formal/credentialed learning, which better recognise and signpost their achievements across the lifespan (Gibson, Coleman & Irving, 2016). In the European context, the above drivers and attractors for micro-credentials, coupled with relatively low participation rates in life-long learning, all point to the need for new educational pathways and more flexible delivery channels and fit for purpose credentials. In this respect, micro-credentials may provide an alternative to the one-size-fits-all approach that more education stakeholders wish to move away from in the provision of flexible course offerings. Arguably, micro-credentials offer the flexibility, accessibility and affordability that learners increasingly require. As summarised in a recent European Commission report:

A growing number of adults, with a higher education degree or lower, will need to reskill and upskill through more flexible alternatives than a full degree in order to overcome the gap between the learning outcomes of initial formal qualifications and emerging skills needs in the labour market. Furthermore, the current COVID-19 crisis illustrates the urgency of creating more transparency in the continuing education and training offer. There is emerging evidence that the demand for online learning will continue after the COVID-19 crisis. The value added of flexible alternative credentials has been demonstrated as numerous adults in the workforce have upgraded their skills during lock-down, in order to be in a better position to cope with changes as labour market gradually open up again (Shapiro 2020. p. 2).

While the need to develop more lifelong learners and invest in reskilling to help get people back to work following the COVID crisis is part of the current ‘education playbook’, not everyone accepts the underlying drivers or arguments supporting the development of micro-credentials. For example, Buchanan et al (2020) claim that “…preoccupation with aspirational curriculum reforms like ‘21st century skills’ and ‘micro-credentials’ promoted to achieve employment growth can be a distraction from what successful education systems can achieve” (p. 2). A participant in a recent survey on the status of micro-credentials in Canadian colleges and institutes reports:

Micro credentials started as an idea but remains a solution looking for a problem. It remains an unproven concept for most jurisdictions and institutions. It lacks common understanding and definition ... To be clear, the idea may have merit, but I remain cautious and somewhat sceptical (Colleges & Institutes Canada, 2021, p. 12).

In a stinging critique, Ralson (2021) adopts a Post-digital-Deweyan perspective to argue that the micro-credential is nothing more than a case of ‘learning innovation theater’ (p. 83). Beyond the novelty factor, at a deeper level, Ralson (2021) claims that higher education institutions are selling their soul to business interests and market forces by unbundling the degree to quickly bolster their profits. A newfound emphasis on future skills and vocational training is at the expense of educating the whole person. As Ralson (2021) writes:

The craze represents a betrayal of higher education’s higher purpose and a loss for students and faculty who continue to see university learning as more than vocational training. (p. 92)

While sweeping generalisations are usually problematic, the critical point is that the micro-credentialing movement is part of a wider social practice. Arguably, the drive to unbundle the traditional degree can be traced to the forces of what has been described as the ‘neoliberal learning economy’ (Ralson, 2021, p. 83). Higher education takes the form of a commodity, a product or service, marketed and sold and acquired like any other commodity in this economy. The logic is that micro-credentials are part of a wider discourse that seeks to erode the public good of higher education despite the purported benefits linked to life-wide and lifelong learning. Even if one is sympathetic to this line of critique, there is more to the micro-credential story than we have revealed thus far. Importantly, micro-credentials have many different faces and should not be treated or generalised as a single uniform entity. This type of critical stance oversimplifies the micro-credentialing movement, as we illustrate over the remainder of this paper.

Key stakeholders with a vested interest in developing and successfully implementing micro-credentials include learners, educational institutions, employers, professional bodies, quality assurance and regulatory agencies (see Table 2). Other notable stakeholders include trade unions, national bodies representing educational institutions and various government departments.

Table 2: Key micro-credential stakeholders

|

Stakeholder |

What’s at stake? |

Learners |

Evidence of achievement, personal success, future employment and career opportunities |

Educational Institutions |

Reputation, relevance of course offerings, relationship with industry partners, quality and integrity of qualifications |

Employers |

Indication of graduate employability, employee skills and provision of ongoing training and professional development |

Professional Bodies |

Relevance and fit for purpose nature of credentials to meet current and future professional needs |

Quality Assurance Agencies and Regulators |

Quality and coherence of credentials and alignment to intended learning outcomes |

A European study interviewing different micro-credential stakeholders (learners, employers, regulators, and higher education institutions found each group had differing priorities and expectations (MicroHE Consortium, 2019). For example, learners wanted short, effective, up-to-date courses. They viewed recognition as an added bonus, whilst employers called for clarity regarding the competencies gained and valued courses that addressed specific skills. In addition, higher education institutions appear to expect micro-credentials to be less bureaucratic and emphasise accreditation for building trust (MicroHE Consortium, 2019).

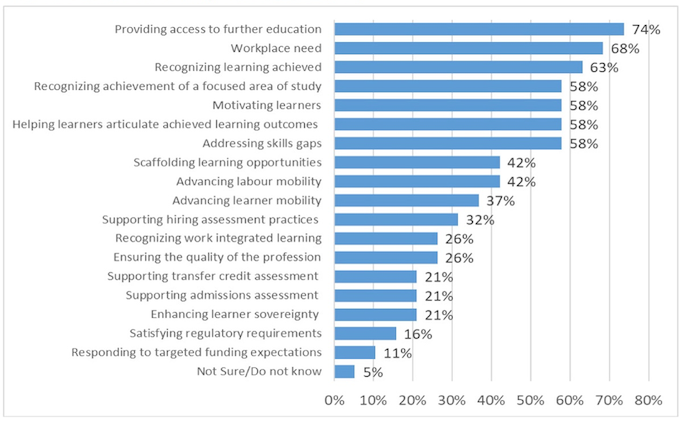

Figure 5: Motivations for offering micro-credentials (n = 19)

More recently, the MICROBOL survey based on a single response from each European country reports the main purpose for which micro-credentials are being promoted (Lantero, Finocchietti & Petrucci, 2021). The most frequent option was 'to increase learners’ competitiveness for the labour market' (n = 21), followed by 'for academic purposes/further studies' (n = 19) and 'recognising credits or prior learning' (n = 19). The rationale reported in this European study contrasts with yet another national Canadian survey where 74% of respondents from 19 post-secondary providers of micro-credentials state the main motivation is to ‘Provide access to further education’ (Duklas, 2020). As illustrated in Figure 5, the next significant motivators behind providing access to further education included “addressing a specific workplace need” and “recognizing learning achieved”. The same study notes that 22% of respondents reported employers had been requesting micro-credentials, indicating some pent-up demand.

While there has been limited research into the employer perspective, the available literature indicates that awareness and experience with micro-credentials are low. A study of 750 human resources executives in the United States by Gallagher (2018) found that only a small proportion of the participants reported hiring an individual with digital badges (14%) or micro-credentials (10%). However, 55% of the respondents agreed that micro-credentials were “likely to diminish the emphasis on degrees in hiring over the next 5-10 years” (Gallagher, 2018, p. 14). Similarly, in a study among recruiters in Ireland in 2018, 74% of respondents reported that digital badges were not important in the recruitment process. However, at the same time, 55% put digital badges at the top of their list of topics of interest, indicating that they want to learn more about them (QQI, 2019).

Another Irish-based study by the Food Industry Training Unit at University College Cork (UCC), focusing specifically on the Food Sector, found that 70% of the employers found it difficult to assess how a digital badge could be of benefit to their business and sector (Corrigan-Matthews & Troy, 2019). However, they largely attributed this perception to their lack of knowledge and experience with digital badges. The same study also surveyed trainees, who had earned a digital badge. The majority (96%) indicated that they would be happy to display a digital badge on their online profiles. Over 80% believed that earning a digital badge would be useful or very useful to them in the future (Corrigan-Matthews & Troy, 2019).

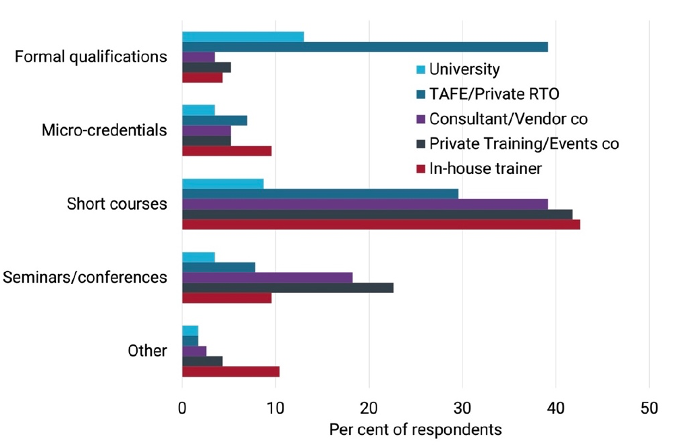

Figure 6: Level of interest in micro-credentials for employee training and development

A recent Australian report aimed at responding to the skills urgency found that few companies were interested in accessing micro-credentials as part of their employee training and development, as shown in Figure 6 (The Australian Industry Group, 2021). While a study of Canadian employers found they were unclear about the meaning of the word “micro-credential,” with 59% of respondents “not familiar at all”, after providing a definition about 60% reported they would increase their confidence in a prospective employee’s skills (Pichette, Brumwell, Rizk & Han, 2021). Overall, around 70% of the 201 employers who participated in this national survey saw the potential role that micro-credentials could play in training, employee retention and lifelong learning more generally.

The need to educate employers and consult with professional bodies in the development of micro-credentials is further demonstrated by the Joint ETUC–ETUCE (2020) position statement on micro-credentials. This confederation of trade unions expressed serious concerns that micro-credentials may be harmful to acquiring and recognising full qualifications. In many respects, this position paper supports a European-wide approach to micro-credentials where they are complementary to full qualifications, quality assured and accredited in accordance with the EQF and national qualification frameworks. However, the point needs noting that current employment contracts typically only recognise and reward employees who attain formal qualifications. As the field evolves, more research is needed to understand different stakeholder perspectives better, particularly if institutions and governments want to develop a coherent micro-credential strategy.

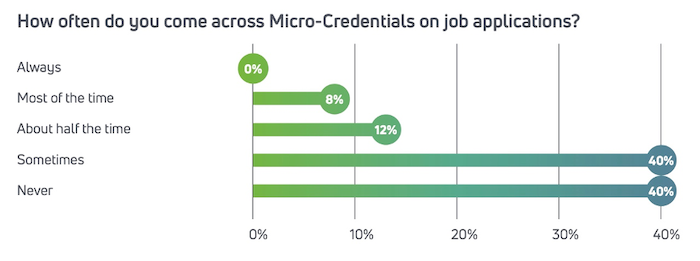

To this end, a national survey of Irish employers and employees on micro-credentials was undertaken in July 2020 by a DCU research team in tandem with Skillnet, a major government-funded agency (Nic Giolla Mhichil, Brown, Beirne & Mac Lochlainn, 2021). While the survey found that nearly half of employers (49%) had heard of the term ‘micro-credential’, only 37% of employees had any awareness. Self-reported levels of understanding also varied greatly, and notably, 80% of employers said they ‘never’ or only ‘sometimes’ came across them on job applications (see Figure 7). In comparison, only 20% of employees had earned a micro-credential.

Figure 7: Reference to micro-credentials in job applications

Employee objectives for earning a micro-credential appear motivated predominantly by internal progression and the enhancement of skills and knowledge for their current role. Less emphasis was placed on micro-credentials as a means of furthering formal education or in seeking a new role. Furthermore, when asked what they might do with a micro-credential, only 31% said they would look into using it as a pathway to a larger qualification. Similarly, employers saw micro-credentials to recognise and reward personal growth and progression among the workforce, rather than quantify existing skills or increase competitiveness. Connecting micro-credentials with strategic competence and continuing professional development was notable in its absence by employer respondents.

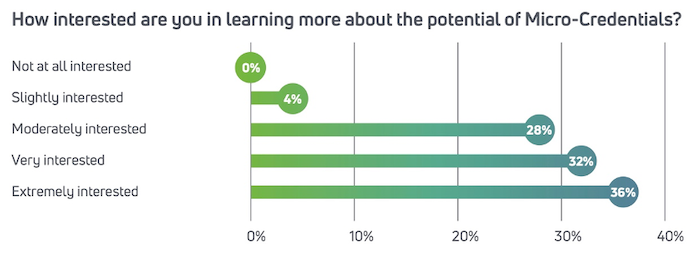

Figure 8: Irish employers interest in learning more about micro-credentials

Despite varying levels of understanding, both employers and employees expressed a strong interest in micro-credentials and a desire to learn more about them, as evidenced in Figure 8. Additionally, a large majority of both employers (64%) and employees (63%) were either “extremely” or “very” interested in learning more about micro-credentials, suggesting that many are intrigued by them, even if they are unaware of what they entail and how they relate to other credentials and qualifications.

Table 3: Benefits associated with micro-credentials for key stakeholders

|

|

|

Learner/Employee |

Employer/Company |

Educator/University |

|

|

|

In summary, there remains a patchy understanding of the micro-credentialing movement amongst key stakeholders, particularly employers and professional bodies, which is no doubt partly due to the lack of a common definition and limited alignment to existing qualification frameworks. Also, evidence suggests the level of awareness amongst educators and learners is relatively immature. Therefore, more needs to be done to engage different stakeholders in discussions around the value and benefits of micro-credentials. Mindful of this point, and building on the work of Resei, Friedl, Staubitz and Rohloff (2019), Table 3 above outlines some of the perceived benefits associated with and arising from micro-credentials for three of the key stakeholders.

A number of initiatives have already been mentioned but micro-credential projects and developments are emerging almost monthly and gaining momentum across the globe. To help stay abreast of new developments, the National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL) at DCU maintains The Micro-credential Observatory (see https://www.dcu.ie/nidl/micro-credential-observatory). This research observatory aims to keep track of major policy developments and relevant national and international reports, with updates to the repository every week. Additionally, in March 2021, the NIDL team launched a facilitated MOOC through the FutureLearn platform exploring the growth of micro-credentials in partnership with the ECIU University. Almost 1,000 educators worldwide participated in Higher Education 4.0: Certifying Your Future, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9: FutureLearn course exploring micro-credentials

These two examples demonstrate how Ireland has established a reputation for its pioneering work in the area of micro-credentials. For example, the Irish Universities Association (IUA) has recently secured €12 million under the government’s Human Capital Initiative (HCI) to develop a national micro-credential system for universities over the next five years. This funding will enable Ireland to establish a coherent national framework for ECTS-bearing micro-credentials, a system of certified qualifications in short courses delivered in flexible formats. This first-of-its-kind project in Europe will increase the capacity of the university sector ‘to extract and adapt high-demand modules from existing programmes, and develop tailored courses, to suit the needs of enterprise and learners’ (IUA, 2020).

Table 4 summarises some of the other major developments announced by different countries over the past two-years (2019-2021). Developments in Australia, Canada, and the Netherlands, in particular, indicate a move toward adopting uniform national approaches to micro-credentialing, and the supra-national body, the European Union, is following at pace in this direction. Since the publication of the final report of the European Commission’s Consultation Group on Micro-credentials, with a roadmap for the future, a public consultation process has been launched, closing in July 2021. As outlined in the table below, a common European approach to micro-credentials is a key priority in the new Skills Agenda for Europe (European Commission, 2020b).

Table 4: Breakdown of projects and initiatives by country

|

|

On the June 22, 2020, the Australian Government announced its plans to build a $4.3 million online micro-credentials platform or market place in response to recommendations resulting from a review of the Australian Qualifications Framework published in 2019. A national survey of micro-credentialing practices in Australassian universities published by ACODE in August 2020 showed only 32% of responding institutions (n = 11) have an approved matrix to determine the level of a micro-credential or badge linked to the levels of learning associated with the National Qualifications Framework. Less than 10% of the responding universities reported the adoption of micro-credentials at a mature status (Selvaratnam & Sankey, 2020). |

|

The New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) conducted three micro-credential pilots in July 2017 – June 2018 with Udacity, Otago Polytechnic and Young Enterprise Scheme. As a result of these pilots, the NZOA has now released a micro-credential system that aligns with their national Qualification Framework. This initiative, however, does not have university backing. In 2019, The New Zealand Tertiary Education Commission also introduced a public funding system for micro-credentials which means that all New Zealand Higher Education Institutions are eligible to apply for the funding that will help them deliver micro-credential programmes (Tertiary Education Commission, 2019). |

|

Following a consultation process and several draft publications, in July 2020 the Malaysian Qualification Agency (MQA) published a Guideline to good practices: Micro-credentials. The guidelines define a number of key principles, general policies and design and delivery considerations for developing micro-credentials from a quality perspective. |

|

On June 16, 2020, the Association of the Registrars of the Universities and Colleges of Canada (ARUCC), which serves 273 Universities and Colleges in Canada as well as number of provincial data exchange hubs, provincial governments and credential evaluators, announced that it was partnering with Digitary, as the digital credentials platform provider of choice for its national network. Once operational, over three million learners across Canada will be able to access and share their official digital credentials online via Digitary. |

|

It is difficult to provide a succinct summary of micro-credential projects and initiatives in the United States as accreditation is largely state-based. However, according to a report by non-profit, Digital Promise, more than 10 state education agencies are running official pilot programs for micro-credentials, with five more trialling micro-credentials in some form. UC Berkley offers a useful case study of a university having established a high level task force on micro-credentials which has already proposed a number of recommendations. The University of Buffalo offers a comprehensive suite of offerings from undergraduate to continuing education with primary focus on knowledge domains. |

|

In the Netherlands, SURF is developing an infrastructure through which Dutch educational institutions can issue digital certificates, called edubadges. A number of pilot projects have been supported and the platform based on blockchain technology is due to launch before the end of 2021. |

|

In Italy, Cineca is a non-profit consortium made up of 70 Italian universities, eight Italian research institutes and the Italian Ministry of Education. The project’s managers collaborate with universities across Italy to develop badges as proof of competence for academic achievement. The universities use them to strengthen the commitment of their students, especially for those courses that are not compulsory, such as those on social and communication skills development and Sustainable Development Goals. Badges can now be stored on a blockchain. |

|

In May 2019, the European MOOC Consortium, consisting of the main European MOOC platforms, FutureLearn, France Université Numérique (FUN), OpenupED, Miríadax and EduOpen, announced a Common Microcredential Framework (CMF). DCU was one of the first universities in Europe to adopt this framework for the development of their micro-credentialing initiative. In 2020, the European Commission established a high-level Consultation Group for micro-credentials to develop a common approach across Europe. In July 2020, the European Commission launched the new ‘Skills Agenda for Europe’, which contains 12 pillars, with one devoted to the importance of micro-credentials. A second pillar was devoted to a new EuroPass platform. Europass is an online framework of tools and information to help EU citizens communicate their skills, experience and qualifications with employers. Incorporated in this framework are software and services for education and training institutions to issue digital credentials (e.g., qualifications, diplomas, certificates). Other Funded European Projects MicroHE is an Erasmus+ project, which plans to measure the current state and trends, develop models for future impacts of micro-credentials, propose instruments (such as credit supplement) for transparency of credentials and build a prototype for a European credential repository. OEPass (2020) is a project that aims to improve the recognition and portability of open learning by developing a ‘learning passport’ that will provide a common standard across universities for describing these learning experiences in terms of ECTS. MICROBOL is a project that aims to link micro-credentials to the Bologna key commitments and support ministries and stakeholders in exploring new credentialing developments within the Bologna Process. |

The development of micro-credentials is not limited to countries as, over recent years, there have been several notable industry initiatives. Major international IT companies, in particular, have started to embrace badging systems for internal recognition and professional development. For example, IBM offers badges to both their staff and the wider public through their partnership with Coursera. They also established a partnership with North Western University so that IBM badges can be used towards professional master’s degree programs at the university. In 2018, Google launched an Online IT support certificate through Coursera and created a consortium of more than 20 employers interested in hiring completers. More recently, Google has launched its Career Certificates designed to develop job-ready skills without people needing to attend a college or university.

Amazon decided in 2019 to spend (US) $700 million to retrain 100,000 of its employees outside the traditional education system using its own credential programs. The EY badging system, launched in 2017, offers staff the opportunity to upskill by earning a badge in data visualization, AI, data transformation and information strategy. The badges are hosted by a third-party platform, Acclaim by Credly. CISCO also uses the Acclaim platform to offer badges to its employees. Notably, Siemens launched their unique STEM skills programme with digital badges for children and teenagers. Furthermore, Microsoft awards both professional certificates and digital badges to individuals who successfully pass their examinations.

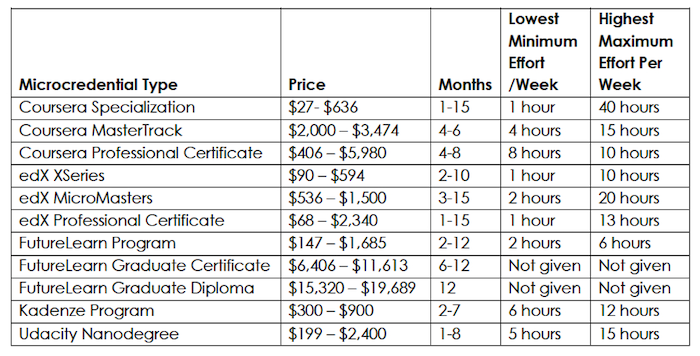

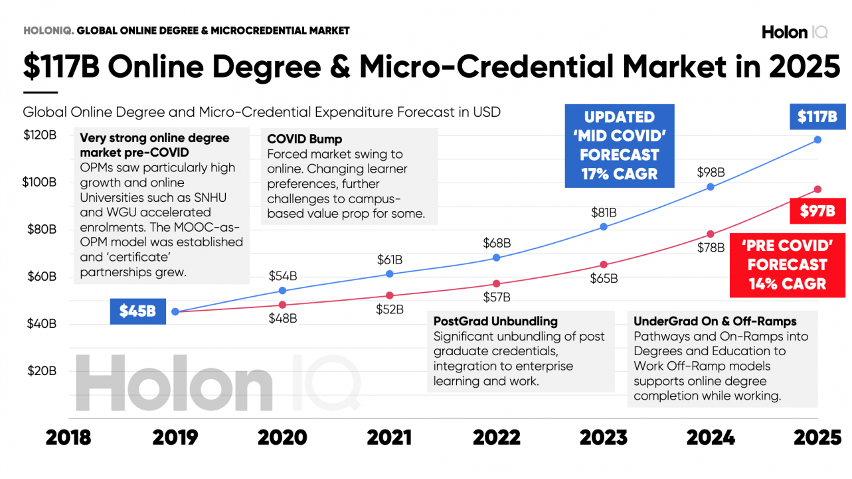

Table 5: A comparison of MOOC-based micro-credentials by type

As previously indicated, MOOC platforms are also an important global player in the development of micro-credentials. More to the point, as HolonIQ (2021a) reveal through their detailed analysis, the global online degree and the micro-credential market is predicted to grow exponentially over the next few years, with an estimated value of US $118 billion by 2025. Hence, as Figure 10 shows, micro-credentials are big business! Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that our analysis suggests that many universities with pioneering micro-credentialing initiatives underway working with industry partners appear to be predominantly hosting them on MOOC platforms. That said, there are several notable exceptions in Deakin University and RIMT University in Australia and, more recently, Athabasca University in Canada.

Figure 10: Predicted growth in the global market for micro-credentials

Taking a closer look at MOOC-based micro-credentials, Pickard, Shah, and De Simone (2018) published an analysis of 450 micro-credentials offered on five MOOC platforms (Coursera, edX, Udacity, FutureLearn & Kadenze), as presented in Table 5. They concluded that the micro-credential offerings lacked consistency and standardisation, pointing out that there was as much variability within each type of micro-credential across different types. While this study is now dated, these inconsistencies remain and continue to make it difficult for both employers and learners to evaluate the significance of a micro-credential offering and compare them. Pickard (2018) points out:

While all employers understand that a master’s degree signifies a higher level of preparation than a bachelor’s degree, it is impossible to say whether a Udacity Nanodegree prepares a person more or better than an EdX Professional Certificate or a Coursera Specialization.

Despite the lack of a common language for micro-credentials, as noted earlier in this paper, and many other challenges facing those promoting a new future-fit credential ecology for the 21st century, the micro-credentialing movement does not appear to be losing momentum. Accordingly to HolonIQ (2021b), based on the results of an online survey of over 300 senior education leaders, over 85% of institutions see alternative and micro-credentials as an important strategy for their future. Our survey conducted as part of the FutureLearn MOOC on Higher Education 4.0 mirrors this result. Notably, 85% of participants reported that over the next five to 10 years, micro-credentials will become a core feature of the suite of credentials offered by higher education institutions.

This article has provided a snapshot of the global micro-credential landscape. In this final section we highlight five main takeaways from the rapidly evolving field as micro-credentials look to become an established feature of the credential ecology, both nationally and internationally.

The key message underlying this paper is that a common definition, set of guiding principles and clearly defined roadmap is required to advance the micro-credentialing movement beyond so-called “warm body” badges. However, the situation is changing quickly worldwide, and governments and quality assurance agencies have a key role in building the infrastructure and funding trusted and quality assured micro-credentialing initiatives. Realising the potential contribution of micro-credentials to help reimagine existing qualification frameworks is not trivial work. It requires educators, policy-makers, and other key stakeholders to clearly understand the problem that micro-credentials seek to address. Crucial to future success, especially if micro-credentials will be more than another passing educational fad, is developing greater understanding along with trusted and coherent national and international credential frameworks. Such frameworks need to recognise the contribution micro-credentials can make across several domains, including employability, life-long learning and education for citizenship. Put another way, as we often conclude, the development of micro-credentials needs to be in the service of these big ideas, not as a big idea in itself.

ARUCC. (2020). ARUCC partners with Digitary to build the Canadian National Network [press release]. https:// e54b1a5c-a1c1-4de5-92be-372a9479ac65.filesusr.com/ugd/5bcc07_25aca1d75ef040708d1e87318cef59d9.pdf

Bariso, J. (2020). Google has a plan to disrupt the college degree. Inc, 19 August. https://www.inc.com/justin-bariso/google-plan-disrupt-college-degree-university-higher-education-certificate-project-management-data-analyst.html

Beirne, E., Nic Giolla Mhichil , M., & Brown, M. (2020). Micro-credentials: An evolving ecosystem – Insights paper. Dublin City University. https://icbe.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Micro-Credentials-Insight-Paper_Aug2020-compressed.pdf

Boud, D., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2021). The move to micro-credentials exposes the deficiencies of existing credentials. The Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 12(1),18-20.

Brown, M., Mac Lochlainn, C., Nic Giolla Mhichíl, M., & Beirne, E. (2020). Micro-credentials at Dublin City University [Paper presentation]. EDEN 2020 Annual Conference, Timisoara. https://youtu.be/KPMSKIbfQXo

Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl, M., Mac Lochlainn, C., Pirkkalainen, H., & Wessels, O. (2021). Paving the road for the micro-credential movement: ECIU University white paper on micro-credentials. European Consortium of Innovative Universities. https://assets-global.website-files.com/551e54eb6a58b73c12c54a18/600e9e7dff949351b6937d73_ECIU_micro-credentials-paper.pdf

Buchanan J., Allais S., Anderson M., Calvo R. A., Peter S., & Pietsch T. (2020). The futuresof work: What education can and can’t do. Paper commissioned for the UNESCO Futures of Education report (forthcoming, 2021). https://digitalskillsformation.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/UNESCO-The-futures-of-work-what-education-can-and-cant-do-2020.pdf

Chakroun, B., & Keevy, J. (2018). Digital credentialing: Implications for the recognition of learning across borders. Paris, France: UNESCO. Available from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264428

Colleges & Institutes Canada. (2021). The status of microcredentials in Canadian colleges and institutes: Environment scan report. https://www.collegesinstitutes.ca/policyfocus/micro-credentials/

Contact North. (2021, May 20). 10 key actions to ensure micro-credentials meet the needs of learners and employers. https://teachonline.ca/tools-trends/10-key-actions-ensure-micro-credentials-meet-needs-learners-and-employers

Corrigan-Matthews, B., & Troy, A. (2019). Developing new learning technologies: Digital. https://www.skillnetireland.ie/publication/developing-new-learning-technologies-taste-4-success- skillnet/

Craig, R. (2015). College disrupted: The great unbundling of higher education. Palsgrave McMillan.

Department of Education (2020, June 22), Marketplace for online credentials [press release]. https://ministers. dese.gov.au/tehan/marketplace-online-microcredentials

Deloitte (2019). Premium skills: The wage premium associated with human skills. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-premium-skills-deakinco-060120.pdf

Duklas, J. (2020). Micro-credentials: Trends in credit transfer and credentialing. BCCAT. https://www.bccat.ca/pubs/Reports/MicroCredentials2020.pdf

ETUC – ETUCE. (2020, July 2). Joint ETUC – ETUCE position on micro-credentials in VET and tertiary education. https://www.etuc.org/en/document/joint-etuc-etuce-position-micro-credentials-vet-and-tertiary-education

Euromonitor. (2017). Current trends in the global education sector. https://www.euromonitor.com/current- trends-in-the-global-education-sector/report

Eurostat. (2020). Adult participation in learning by sex. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=sdg_04_60 (Accessed 9th of March, 2020).

European Commission. (2020a). Final report: A European approach to micro-credentials. Output of the Micro-credentials Higher Education Consultation Group. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/european-approach-micro-credentials-higher-education-consultation-group-output-final-report.pdf

European Commission. (2020b). European Skills Agenda. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1223

European MOOC Consortium. (2019). The European MOOC Consortium (EMC) launches a Common Microcredential Framework (CMF) to create portable credentials for lifelong learners [Press release]. https://www.futurelearn.com/info/ press-releases/the-european-mooc-consortium-emc-launches-a-common-microcredential-framework-cmf-to-create- portable-credentials-for-lifelong-learners

Gallagher, S. R. (2018). Educational credentials come of age: A survey on the use and value of educational credentials in hiring. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/520913

Gibson, D., Coleman, K., & Irving, L. (2016). Learning journeys in higher education: Designing digital pathways badges for learning, motivation and assessment (pp. 115-138). In D. Ifenthaler, N. Bellin-Mularski, & D. Mah (Eds.), Foundation of digital badges and micro-credentials: demonstrating and recognizing knowledge and competencies. Springer.

HolonIQ. (2021a, June 26). Online degree and micro-credential market to reach $118B by 2025. https://www.holoniq.com/markets/higher-education/global-online-degree-and-micro-credential-market-to-reach-117b-by-2025

HolonIQ. (2021b). Micro-credentials executive panel survey. Available from https://mcusercontent.com/f24f06c8cd312356e0efe7496/files/e6a916e6-6937-4c41-a96f-b68c44340b40/HolonIQ_Micro_Credentials_Exec_Panel_March_2021.pdf

HolonIQ. (2020, June 26). 2.5x Global MOOC Web traffic. https://www.holoniq.com/notes/global-mooc-web- traffic-benchmarks/

International Council of Distance Education. (2019). Report of the ICDE Working Group on the Present and Future of Alternative Digital Credentials (ADCs). https://www.icde.org/knowledge-hub/2019/4/10/the-present-and-future-of-alternative-digital-credentials

Irish Universities Association. (2020). IUA universities secure €106.7 million funding under HCI Pillar 3. 5th October. https://www.iua.ie/press-releases/iua-press-release-5th-oct-iua-breaks-new-ground-with-e12-3-million-mc2-micro-credentials-project-under-hci-pillar-3/

Kato, S., Galán-Muros, V., & Weko, T. (2020). The emergence of alternative credentials. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 216. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/the-emergence-of-alternative-credentials_b741f39e-en;jsessioni d=NIawrexYicohkpj7F8tEUJ-I.ip-10-240-5-155

Kazin, C., & Clerkin, K. (2018). The potential and limitations of microcredentials. Service Members Opportunity Colleges. http://supportsystem.livehelpnow.net/resources/23351/Potential%20and%20Limitations%20of%20Microcredentials%20FINAL_SEPT%202018.pdf

Lantero, L., Finocchietti, C., & Petrucci, E. (2021). Micro-credentials and Bologna key commitments: State of play in the European higher education area. CIMEA. https://microcredentials.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/02/Microbol_State-of-play-of-MCs-in-the-EHEA.pdf

Manyika, J., Lund, S., Chui, M., Bughin, J., Woetzel, J., Batra, P., Ko, R., & Sanghvi, S. (2017). Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation. McKinsey Global Institute.

MicroHE Consortium (2019). A briefing paper on the award, recognition, portability and accreditation of micro-credentials: An investigation through interviews with key stakeholders & decision makers. https://microcredentials.eu/wp- content/uploads/sites/20/2019/12/WP3-Interviews-with-Key-Stakeholders-Decision-Makers-Overall-Summary-Report.pdf

MicroHE Consortium (2020). MicroHE. https://microcredentials.eu/

National Institute for Digital Learning. (2020). The Micro-credential Observatory. Available from https://www.dcu.ie/nidl/micro-credential-observatory

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2019). Approval of Micro-credentials. https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/providers-partners/approval-accreditation-and-registration/micro-credentials/

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2019). Guidelines for Applying for Approval of a Training Scheme or a Micro-credential. https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/providers-partners/approval-accreditation-and-registration/micro-credentials/guidelines-training-scheme-micro-credential/

Nic Giolla Mhichil, M., Brown, M., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn, C. (2021). A micro-credential roadmap: Currency, cohesion and consistency. National Irish Feasibility Study and Survey of Micro-credentials. Dublin City University. https://www.skillnetireland.ie/publication/a-micro-credential-roadmap-currency-cohesion-and-consistency/

OECD. (2019). Trends shaping education 2019. OECD Publishing.

OEPass. (2020). Open education passport. https://oepass.eu/

Oliver, B. (2019). Making micro-credentials work for learners, employers and providers. Deakin University. https://dteach.deakin.edu.au/2019/08/02/microcredentials/

Pichette, J., Brumwell, S., Rizk, J., Han, S. (2021) Making sense of microcredentials. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. https://heqco.ca/pub/making-sense-of-microcredentials/

Pickard, L. (2018). Analysis of 450 MOOC-based microcredentials reveals many options but little consistency. https://www.classcentral.com/report/moocs-microcredentials-analysis-2018/

Pickard, L., Shah, D., & De Simone, J. (2018). Mapping micro-credentials across MOOC platforms (pp. 17–21). Presented at the 2018 Learning With MOOCS (LWMOOCS), IEEE.

Ralson, S. J. (2021). Higher education’s microcredentialing craze: A postdigital-Deweyan critique. Postdigital Science and Education, 3, 83-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00121-8

Resei, C., Friedl, C., Staubitz, T., & Rohloff, T. (2019). Result 1.1c Micro-credentials in EU and Global. https://www.corship.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Corship-R1.1c_micro-credentials.pdf

Rossiter, D., & Tynan, B. (2019). Designing and implementing micro-credentials: A guide for practitioners. Commonwealth of Learning. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3279

Selvaratnam, R., & Sankey, M. (2020). Survey of micro-credentialing practice in Australasian universities. An ACODE White Paper. https://www.acode.edu.au/pluginfile.php/8411/mod_resource/content/1/ACODE_MicroCreds_Whitepaper_2020.pdf

Shah, D. (2020a). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2020. https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-stats-2020/

Shah, D. (2020b). How different MOOC providers are responding to the pandemic. https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-providers-response-to-the-pandemic/

Shapiro, H. (2020). Background paper for the first meeting of the Consultation Group on Micro-credentials. https://www.heilbronn.dhbw.de/fileadmin/downloads/news/ab_2014/Background_paper_on_Micro-credentials.pdf

Sturgis, C. (2019). What’s the difference between micro-credentials and badges? https://www.learningedge.me/ whats-the-difference-between-microcredentials-and-badges/

SURF. (2020). Lessons learned pilot Edubadges: Experiences with digital badges in Dutch education system. https://www.surf.nl/en/lessons-learned-pilot-edubadges

Tertiary Education Commission. (2019). Micro-credentials - funding approval guidelines. Tertiary Education Commission. https://www.tec.govt.nz/news-and-consultations/archived-news/micro-credentials-funding-approval-guidelines-available/

The Australian Industry Group. (2021). Skills urgency: Transforming Australia’s workplaces. Centre for Education & Training. https://cdn.aigroup.com.au/Reports/2021/CET_skills_urgency_report_apr2021.pdf

The Institute for the Future. (2017). The next era of human machine partnerships: Emerging technologies’ impact on society and work by 2030. https://www.delltechnologies.com/content/dam/delltechnologies/assets/perspectives/2030/pdf/SR1940_IFTFforDellTechnologies_Human-Machine_070517_readerhigh-res.pdf

UNESCO. (2018). Digital credentialing: Implications for the recognition of learning across borders. UNESCO Education Sector. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000264428

World Economic Forum. (2020). The future of jobs report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020

Authors:

Professor Mark Brown is Ireland’s first Professor of Digital Learning and Director of the National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL) at Dublin City University (DCU). He serves on the Executive Committee of the European Distance and E-learning Network (EDEN) and is a member of the Supervisory Board of the European Association of Distance Teaching Universities (EADTU). Mark is also Vice-President of the Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia (ODLAA). In 2017, the Commonwealth of Learning recognised Mark as a world leader in Open and Distance Learning. In 2020, Professor Brown served on the European Commission’s high-level consultation group on developing a policy response to the growth of micro-credentials. Email: mark.brown@dcu.ie

Professor Mairéad Nic Giolla Mhichíl is responsible for academic leadership in the area of micro-credentials at Dublin City University (DCU). She also plays lead roles in the national MC2 micro-credentialing initiative along with the ECIU University. Mairead is Head of the NIDL Ideas Lab and before then was the Associate Dean of Teaching and Learning in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences with academic responsibility for forty-five academic programmes. In 2016 she was a Fulbright Tech Impact Scholar working with the University of Notre Dame in researching the design and development of a Massive Open Line Course. Since this experience she has gone on the lead the development of DCU’s MOOCs on the FutureLearn platform. Email: mairead.nicgiollamhichil@dcu.ie

Dr Elaine Beirne is a Research Officer in The Ideas Lab in the National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL) at Dublin City University. She has particular interests in the area of micro-credentials as well as the role emotion plays in online learning environments. Elaine also played a leading role in the design and development of A digital edge: Essentials for the online learner, a free online course offered through the FutureLearn platform. Email: elaine.beirne@dcu.ie

Conchúr Mac Lochlainn is a Research Officer and PhD student in The Ideas Lab in the National Institute for Digital Learning (NIDL) at Dublin City University. He plays a major role at DCU in the European-funded ECIU University initiative, which involves the development of micro-modules and micro-credentials following a Challenge-based Learning (CBL) approach. In 2021, Conchúr played a key role in the design and delivery of Higher Education 4.0: Certifying Your Future, a free online course exploring the growth of micro-credentials. Email: conchur.maclochlainn@dcu.ie

Cite this paper as: Brown, M., Mhichil, M. N. C., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn, C. (2021). The global micro-credential landscape: Charting a new credential ecology for lifelong learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228-254.