2021 VOL. 8, No. 2

Abstract: This paper reports on the use of Engeström’s (1987) Activity Theory (AT) framework to gain insights into the contradictions that emerge within the activity system of the online component of an advanced writing skills course, delivered in a blended-learning mode using the Process Approach. Activity theory, with its principle of contradictions, has been used successfully to identify tensions that arise in interactions between and among participates in online environments. The focus of this mixed-method study was to identify challenges participants experienced due to externally imposed conditions when engaging in the online activities. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews and the online log reports from the Learning Management System (LMS). Contradictions emerged between and among the elements of two activity triangles within the activity system of the online writing course. Implications of these contradictions were noted to take steps to improve the design of the online component of the writing course.

Keywords: activity theory, contradictions, advanced writing skills, blended learning, Process Approach.

Academic writing is an indispensable skill for undergraduates in HE institutions, but it is also one of the most complex skills that can be mastered. Research indicates that second-language learners find it very challenging to master academic writing in their disciplines (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996; Jones, 1999; Kroll, 1990). In the Sri Lankan context, this problem was evident in the conventional universities (Fonseka, 2008; Illangakoon, 2011/2012; Kumara, 2009; Perera, 2006; Sivaji, 2011/2012), as well as in the Open and Distance Learning (ODL) context at the Open University of Sri Lanka (De Silva, 2014; Raheem & Ratwatte, 2001; Ratwatte, 2005). Reviewing the foregoing studies, it was clear that the ODL learners at the tertiary level, who are ESL learners, required extra support to improve their academic writing skills, particularly their essay writing skills, to meet the demands of their present and future studies. Furthermore, strategic instruction using online technologies was seen to have potential to improve the English academic writing skills of ESL learners which endorses the use of the Blended-learning (BL) mode to teach them (Ferriman, 2013; Liu, 2013; Yoon & Lee, 2010). Since the OUSL had the infrastructure facilities already in place to make this possible, it was decided to conduct an advanced writing skills course in the blended-learning mode to develop the essay writing skills of the learners.

The course aimed to help the learners write coherent and well organised academic essays using a variety of essay organizational patterns. To enable them to develop their essay writing proficiency, an approach that has exerted a significant influence in L2 writing pedagogy and classroom instruction to essay writing, the Process Approach (PA) (Polio, 2001; Raimes, 1985; Silva, 1990; Zamel, 1983), was used.

This paper reports on part of the study that used Engeström’s (1987), Activity Theory (AT) as a framework to gain insight into the contradictions that emerged in the online component of the advanced writing skills course offered in the BL mode. The objective was to ascertain the challenges faced by the participants in engaging in the designed activities due to the externally imposed conditions with the intention of improving the course design. The following research questions were investigated:

Much research has been conducted in the use of the PA in teaching writing in a BL mode (Adas & Bakir, 2013; Ferriman, 2013; Shafiee et al, 2013; Yoon & Lee, 2010). However, there is limited research both internationally and locally in the field of writing research that utilizes the PA, in which the AT framework with its principle of contradictions was used to investigate learner interactions in the online environment.

At an international level, a study conducted only online at a university in New Zealand used AT to determine the positive changes in the operation of a computer mediated writing programme (Brine & Franken, 2006). The findings revealed that the AT framework was effective in highlighting several issues and constraints in the activities pertaining to the co-construction of a text. The tensions that surfaced in the activity system of the task; between the subjects, rules, roles and the division-of-labour revealed that different students had different perceptions about the ways activities were carried out. Some students enthusiastically adopted them while others contested them.

Activity theory as a framework of analysis was also utilized in a study in the Sri Lankan context by Jamaldeen et al (2016). The purpose of this study was to investigate the social and technical activity system relevant to the area of introducing m-learning to enhance English Language Learning among school leavers. In this instance, participants exhibited a strong need to enhance their English language proficiency, and therefore engaged in a number of activities using their mobile devices to access information. Rules set in place were followed by the subjects, and the roles of participants, facilitators and learners were clearly defined and adhered to. Thus, revealing that implementation of an m-learning platform for enhancing the learners English language proficiency has the potential to be successful.

A recent study conducted in the ODL context in Sri Lanka used AT and PA to improve essay writing at the tertiary level. The purpose of this study was to investigate the extent of learners’ interaction with online mediation tools, and the most significant contradiction that emerged was the under-utilisation of the mediation tools due to time constraints, a lack of motivation, and disparate language proficiency (Pullenayegem, De Silva, & Jayatilleke, 2020).

Each of the aforementioned studies used AT as their framework, which highlighted several issues and constraints in activities related to the co-construction of knowledge. However, the results were mixed. While the study at the international level revealed that not all students were keen to engage in the prescribed activities, the 2016 Sri Lankan study showed a higher level of student engagement with participants being eager to enhance their language learning and following the rules set in place. The recent 2020 study in the ODL context in Sri Lanka revealed that the most significant contradiction was the under-utilisation of the mediation tools due to time constraints, a lack of motivation, and disparate language proficiency. This study used the PA to improve the writing skills of learners at the tertiary level. The purpose of the present study helps to fill the gap in the literature by investigating the use of AT and PA to study the contradictions that emerge in relation to learner engagement in online activities due to externally imposed conditions when learning English essay writing in a blended-learning course. As well as to determine how implementation of explicit rules affect interaction and collaboration among learners, and the division-of-labour affects interaction and collaboration among the community.

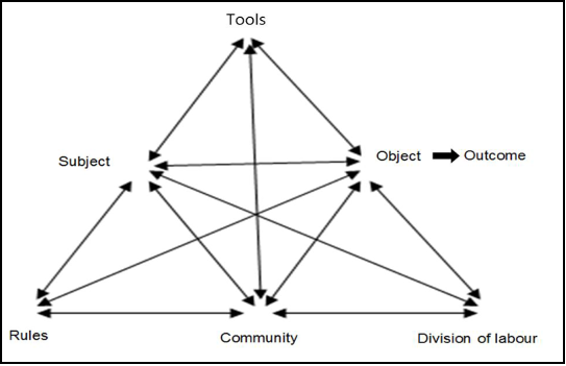

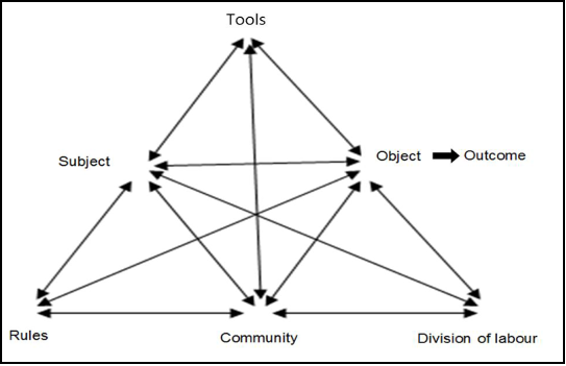

Activity theory is a dynamic framework that is used to understand the complexities that exist in an activity system and is an invaluable aid in bringing to light any contradictions or tensions that can arise within the elements of an activity system or between activity systems (Engeström, 1987, 1999). The structure of the activity theory model consists of two triangles, an outer, larger triangle, and a smaller, inner triangle, with its apex pointing downwards (Figure 1). The three nodes of the larger triangle represent the elements; Tools – Rules – Division-of-Labour (T-R-DoL) of the activity system, and the three nodes of the inner triangle represent the elements; Subject-Community-Object (S-C-O), the lines between the elements in turn form smaller triangles within the activity system. The lines between these six elements represent the relationships between these elements. Furthermore, as researchers point out, any activity system will inevitably contain contradictions, however, these contradictions serve a useful purpose, in that they can cause change and development (Engeström & Meittinen, 1999).

Figure 1: Engeström’s (1987) model of an activity system

The AT framework offers a broad lens of inquiry and has been useful in highlighting contradictions that occurred in schools and institutions of higher learning. A number of studies using AT and its principle of contradiction as a framework have been used in a variety of educational contexts. The use of AT affords opportunity to study these contradictions with a view to bringing about "change, innovation or development" (Ekundayo, et al, 2012, p. 13).

The AT framework was utilized to examine Web-based writing projects, to understand how to develop and sustain long-term writing instruction projects. Contradictions that arose in the activity system of an Online Writing project in a study carried out by Palmquist et al (2009), enabled the team members to identify several contradictions between the elements, and within the elements of the activity system of the project. These contradictions led to changes in the writing support system offered to students following the course, and copyright protection for contributors to the project. Using AT was viewed as extremely beneficial in enabling the team to develop a writing environment to support their student population.

Baran and Cagiltay (2010), using an Internet platform, investigated the effectiveness of the use of online communities of practice (oCoPs) in the professional development of mathematics teachers. The themes that emerged from the participants’ reports were categorised under each component of AT and compared with the data received from the participants’ discussion list messages and interviews. The results of this study show that the use of the AT in analysing the data was effective in evaluating and comparing oCoPs designed and built with a design and implementation processes.

Another study by Gedera and William (2013) utilized AT to identify the tensions and conflicts, and how learner participation was affected due to the contradictions that arose in a fully online course at a university in New Zealand. Several contradictions were noted from the analysis of the PowerPoint presentations and learner messages in the discussion forums of the LMS. These contradictions were found in the presentation of course material as respects readability of texts on the screen, difficulty in downloading some of the podcasts, and lack of adequate planning regarding the individual responsibilities in communicating clear and accurate information to learners. Tensions and contradictions were experienced due to limited teacher guidance and feedback in the discussion forums. The tensions and conflicts encountered showed areas that required improvement.

Barab et al (2002), used AT to analyse the learner and instructor participation in a computer-based three-dimensional (3-D) modeling course for learning astronomy. The tensions in the relationship between learning astronomy and building 3-D models, and the interaction between pre-specified, teacher-directed instruction versus emergent student-directed learning were analysed. The AT analysis revealed that often the actions of model-building and astronomy-learning were the same, and directed-learning emerged from the rules, norms, and divisions-of-labor and not from teacher-directed or student-directed learning. This insight could enable instructional designers and educational researchers to meet the challenge of designing or re-designing courses to ensure that meaningful participation and learning takes place.

The results of the above studies show that the use of AT can contribute significantly to improving the design and implementation of online courses, because the contradictions that emerge highlight areas that need to be given attention for better results.

The focus of this study was the online component of an Advanced Writing Skills course offered in the BL mode to learners of the Diploma in English Language and Literature at the Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL). The course aimed to help the learners write coherent and well-organised academic essays using a variety of essay organisational patterns, for which the Process Approach (PA) was used.

The course consisted of seven (7) face-to-face (f2f) sessions, with each session being of three hours duration. Each session focused on specific stages of the PA to writing: pre-writing, drafting and revising, editing and proofreading, and sharing (publishing), and application of all the stages in writing three types of essay organisational patterns. At the end of each day school session learners were required to participate in the online activities designed for each respective online session. Participants were required to interact with each other, within their assigned groups in discussion forums (DFs). The assigned tasks included giving peer feedback, making needed changes in their assignments based on peer feedback, submitting the edited assignment for tutor feedback, and submitting the final edited copy of the assignment to the final copy forum to share with peers. This paper focuses on how the implementation of explicit rules affects interaction and collaboration among learners, and how the division-of-labour affects interaction and collaboration among the community when engaging in specified online activities (Table 1).

Table 1: Online course activities, rules and division-of-labour

Ses. |

Activities |

Rules |

Division-of-labour |

1 |

Pre-writing (a)

|

|

Individual task

Peer task:

Tutor

|

2 |

Pre-writing (b)

|

||

3 |

Drafting & Revising

|

||

4 |

Editing and Proofreading

|

||

Application – Organizational patterns |

|||

5 |

Compare/contrast essay |

||

6 |

Problem / Solution essay |

||

7 |

Cause / Effect essay |

||

Publishing (Sharing) at all stages |

|||

This study utilised the explanatory sequential mixed methods research design. Both quantitative and qualitative data were used to enhance the validity and the reliability of the research findings. Volunteer participants, who made up the study’s sample, included 64 adult learners composed of females (47), and males (17). The majority were between 20 and 30 years of age, followed by those between 31 and 40 years, with 14 participants being over the age of 41. The majority (39) were teachers, and of these 24 were English-language teachers. Those employed in administrative capacities or were students studying at other universities numbered 17, while two were homemakers, and six were unemployed, respectively.

The quantitative data were collected through log reports in the initial stage. The online log reports automatically recorded the participants’ interaction in the online environment when engaging in the assigned online activities. Thereafter, qualitative data were gathered from semi-structured one-on-one post interviews with 34 participants. A cross section of participants age-wise, and according to their secular and domestic commitments, were chosen. The interview questions focused on the two research questions related to the imposition of rules, and the division-of-labour in the activity system of the online component of the course.

Initially the online logs were filtered to generate data to determine the extent of participation of each participant in conforming to the activity triangles, Subject-Rules-Object (S-R-O), and Community–Division-of-Labour–Object (C-DoL-O) of the activity system of the online course, using the AT framework (Table 2), and the data were analysed. The interview responses were transcribed and coded using the coding procedure; Qualitative Content Analysis (QCA) suggested by Schreier (2012). In order to answer the research questions, two separate coding frames were drawn. The initial coding frame for Research Question 1 was drawn up based on the main category (challenges) and sub-category (conformity to and view of rules). The coding frame for Research Question 2 was based on the main category (challenges) and sub-category (conformity to and view of division-of-labour). The units of coding were the statements or phrases in the responses that meaningfully related to each of the categories.

Table 2: Description of activity system of the Advanced Writing Skills course

|

Nodes |

Description |

Subject |

Learners of the Advanced Writing Skills course |

Object |

To practice writing essays using the stages of the PA. |

Outcome |

To develop the competency in academic writing |

Rules |

The protocols to be followed when engaging in activities |

Community |

The learners and the tutor of the Advanced Writing Skills Course |

Division-of-Labour |

The individual tasks, task between peers, and tutor task. |

Question 1: How does the implementation of explicit rules affect interaction and collaboration among learners when engaging in the specified online activities?

The overall results of the data gathered regarding the activity triangle of the S-R-O presented in Table 3, help to identify contradictions that are described thereafter. Table 3 records the number of participants who engaged in activities in the four sessions of the six stages of the PA, and three sessions of the application stage. This data formed the basis for the questions in the interviews in order to determine challenges encountered by participants in interacting and collaborating with each activity.

Table 3: Overall results of conformity to rules in the S-R-O activity triangle

Total No. of participants in study (n = 64) |

||||||||||

|

Stages of the Process Approach |

Application Stage |

||||||||

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

||||

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

||

Informal /formal text |

Brainstorm / mind map |

Outline |

Body Paragraphs |

Draft and Revise |

Edit and Proofread |

Compare / Contrast |

Problem / Solution |

Cause and Effect |

||

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

||

R |

Total No. of active participants in each Session |

31 |

25 |

27 |

20 |

21 |

5 |

9 |

10 |

12 |

1 |

Produce and upload draft assignment to DF for peer feedback |

26 |

25 |

24 |

19 |

19 |

5 |

9 |

9 |

11 |

2 |

Give at least one feedback comment to a group member only within assigned group |

18 |

11 |

22 |

16 |

15 |

1 |

6 |

4 |

7 |

3 |

Upload revised assignment based on peer feedback to Assignment Box for tutor feedback |

20 |

24 |

13 |

19 |

13 |

5 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

4 |

Upload final revised assignment based on tutor feedback to Final Copy forum for sharing |

14 |

18 |

17 |

8 |

Not Required. |

7 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

As Table 3 shows, of the 64 participants in the study, only 31 participated in the online activities, which is less than half the sample in this study. Session 1, Activity 1, had the highest number of participants (26). Thereafter, the number participating decreased to 20 in Session 2, Activity 2, with the least number of participants (5), recorded in Session 4.

The contradictions that emerged related to the Subject-Rules-Object (S-R-O) triangle of the activity system of the online course are next presented.

The data presented in Table 3 shows that no participant conformed to all the rules. Even though 31 participated in Session 1, Activity 1, only 26 participants conformed to Rule 1. Least conformity to the rules was seen in the Editing and Proofreading Stages; five participants conformed to Rules 1 and 3, and one (1) participant conformed to Rule 2. Thereafter, a nominal increase in conformity to the rules is recorded in the Application Stage that required writing three types of essay organisation using the PA. Furthermore, it is evident that the rule that the majority of participants failed to conform to in all seven sessions was Rule 4; uploading the Final Edited Copy after receiving tutor feedback. This aspect was elaborated on in the interviews in the following responses:

… If others are there and they won’t participate I can’t help. . . [SF-2860-Interview]

I didn’t receive much comment … only one or two … [SF-1557-Interview]

I have two kids and I tried to do a lot because … then sometimes I miss this part because we had to do a lot of work [SF-3526-Interview]

The main reasons for failure to adhere to all the rules as observed in the selected comments of the interviewees were the lack of participation by peers within groups, and constraints of time and family obligations.

The second contradiction that emerged is that some participants found the rules restrictive. This surfaced due to the rule that restricted them to give feedback to only members within their own groups as is observed in the following interview comment:

Well I was tempted to do so, [give comments to members of other groups] but, because, due to the rules you only can comment on that, you know it was like forcefully, like don’t type anything, don’t type anything, but just read. [SM-2622-Interview]

The third contradiction that emerged related to rules was that some participants viewed conformity to all four rules as being difficult, since it required the cooperation of other group members to complete a given activity within a given time frame. Also, too many activities in the process made conformity to the process tedious and confusing. These difficulties are revealed in the following interview comments of the participants:

It was a bit difficult because once I finish, if I finish my paper fast then I would have to upload it then getting some one’s feedback was difficult because sometimes people in the group would not participate at all so like we can wait till some one’s comment or upload something for me to send the assignment to you and then that was a bit frustrating… [SF-3470-Interview]

… without having a long process. Maybe, OK, submit your essay, and maybe comment on someone like make it short, rather than editing and again posting, it’s a bit tedious even for me. [SF-6504-Interview]

There were so many, so many steps to do no! Little bit it confused, it was little bit confused, Madam [SF-3772-Interview]

The fourth contradiction was that conformity to the rules was beyond the control of subjects because of delays in receiving comments on participants’ submissions from peers in the group as typified in the comment below by an English language teacher, who exhibited high proficiency in writing, with a pre-test mark of 68% and a post-test mark of 80% and exemplifies participants’ perception of the rules:

Yes, I would say now, it was like this, now for example, now say an essay, we need to submit it, then we need to comment, and then we need to wait for someone to comment and then incorporate it into our essay, and so it was a bit long, long thing, especially with all the other commitments, … and also we need to wait for someone. That was also, I mean, was not in our hands. So, I mean and it was only after that, that we got tutor feedback [SF-6504-Interview]

Question 2: How does the division-of-labour affect interaction and collaboration among the community when engaging in specified online activities?

Table 4 presents the overall results of the data regarding the activity triangle of the C-Dol-O. The table shows the number of participants who actively engaged in each of the seven sessions in relation to individual, peer, and tutor task (to give feedback on uploaded assignments). Noteworthy contradictions related to the individual tasks, peer task, and tutor task were recorded.

Significantly, the highest number of participants was 31; less than half the sample of 64. Also, contradictions existed in all the tasks: individual, peer, and tutor, related to the C-DoL-O activity triangle. Several contradictions were found to be common to all the nine activities designed for the online component of the course, which will be presented below. Data gathered from the log reports are corroborated with interview comments.

Table 4: Overall results of Division-of-Labour in the C-DoL-O Activity Triangle

Total No. of participants in study (n = 64) |

||||||||||||

|

Stages of the Process Approach |

Application Stage |

||||||||||

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

Sess. |

||||||

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

Act. |

||||

Informal / formal text |

Brainstorm / mind map |

Outline |

Body paragraph |

Draft and Revise |

Edit and Proofread |

Compare / Contrast |

Problem / Solution |

Cause and effect |

||||

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

No. |

||||

Total No. of active participants in each session |

31 |

25 |

27 |

20 |

21 |

05 |

09 |

10 |

12 |

|||

Task |

Individual Task |

|||||||||||

1. |

Produce and upload specified assignments to the DF relative to each stage of the PA for peer feedback |

26 |

25 |

24 |

19 |

19 |

05 |

09 |

09 |

11 |

||

2. |

Revise assignment based on peer feedback |

17 |

15 |

12 |

14 |

14 |

01 |

06 |

03 |

10 |

||

3. |

Upload revised assignment to Assignment Box based on peer feedback for tutor feedback. |

20 |

24 |

13 |

19 |

13 |

05 |

09 |

10 |

11 |

||

4. |

Upload revised assignment based on tutor feedback to Final Copy Forum for sharing |

14 |

18 |

17 |

08 |

Not |

07 |

07 |

06 |

05 |

||

Task |

|

Peer Task |

|

|

|

|

||||||

1. |

Give feedback on at least one submission of a group member |

18 |

11 |

22 |

16 |

15 |

01 |

06 |

04 |

07 |

||

Task |

|

Tutor Task |

|

|

|

|

||||||

1. |

Give feedback on uploaded assignment |

20 |

24 |

17 |

19 |

13 |

05 |

09 |

10 |

11 |

||

The contradictions that emerged related to the C-DoL-O activity triangle of the activity system of the online course are next presented.

The overall results in the C-DoL-O activity triangle, as presented in Table 4 above, help to identify the contradictions between the subject (learner) and the four (4) individual tasks. There was a noticeable decline in the number of participants, as well as the number of submissions in the latter stages of the PA.

The four individual tasks related to the sixth stage of the PA, editing and proofreading in Session 4, saw a significant decline. Thereafter, an overall low engagement was in the individual tasks in the application stage, with the highest, 11 participants, who engaged in writing the cause-and-effect essay, and the lowest, three, in writing a problem/solution essay. Sample comments related to individual tasks are as follows:

I actually, I kind of logged in, and I was just keeping in touch. But I submitted only the first … assignment that is the changing from informal to formal, so I participated only in that. [SF-6504-Interview]

I have two kids and I tried to do a lot because … then sometimes I miss this part because we had to do a lot of work [SF-3526-Interview]

. . . editing was something very hard, because editing means editing our own, our own work was a little difficult because we need to realize what we have written is wrong to find that is a little difficult that was very hard [SF-4668-Interview]

Actually, if I think about it now, I think, I must say, I didn’t consider it [engagement in online activities] so important. I suppose if had, I might have done it … the fault is mine [SF-5537-Interview]

…actually if you can make it compulsory then that is better … somehow I might have done that [SF-2605-Interview]…if we were getting marks then I think I would probably stay up in the nights and you know do it somehow… We didn’t, you know, not very committed to always participate. But then if we were getting marks, I think everyone would at least stay up in the night without worrying about waking up early morning the next day, and somehow finish it [SF-3470-Interview]

These comments reveal several challenges that contributed to low participation in individual tasks. These included time constraints due to family and career commitments as well as disparate language proficiency. Also, the lack of incentive, such as making the task compulsory and giving marks, adversely affected self-motivation.

Engagement in the peer task as presented in Table 4 shows that contradictions emerged between the subject (learner) and peer task. The peer task was to give feedback on at least one submission of a group member. As in the individual tasks, the key issue was the decline in engagement in activities in the latter stages of the PA, including the application stage.

As respects the peer task, a nominal increase from 18 in Activity 1 in Session 1 to 22 in Activity 1 in Session 2 was recorded in the Pre-Activity Stage. Thereafter, there was a sharp decline in participants to a single (1) participant engaging in the Editing and Proofreading Stage in Session 4. Engagement level in the Application Stage, too, decreased to four in Session 6. The following comments highlight the tensions in this area:

Though there were fifteen, I don’t remember the exact amount, twenty in a group but only ten, five to ten members were in that group actively… [SF-3673-Iterview]

… since all were on a last minutes people we get together and tomorrow we try to get views the day before, then we found on the online session, that we don’t get much people at the final hour and since you have to get the feedback we won’t have time to submit the assignment [SM-2622-Interview]

… for example now say an essay we need to submit it, then we need to comment, and then we need to wait for someone to comment and then incorporate it in to our essay and so … especially with all the other commitments, and … and also we need to wait for someone. That was also, I mean, was not in our hands. … I mean and it was only after that, that we got tutor feedback. [SF-6504-Interview]

I try to correct, sometimes, I couldn’t, I don’t have idea about how to correct mistakes [SF-2643-Inteview]

… actually quality from my peers were not all that good [SF-3797-Interviews]

First actually I felt a bit embarrassed … because I remember the discussion [DF] was going on we got to know certain people are quite higher than us and they are good in their vocabulary, and to share ours with errors and all embarrassed [SF-5719-Interview]

The above comments indicate that lack of engagement or delayed engagement in the peer tasks presented a challenge to the participants. Additionally, the disparate language competency of participants caused some who were less proficient to refrain from commenting. Also, those who were less proficient in the English language did not know how to correct mistakes in their own writing. Furthermore, those who were more proficient viewed others’ submissions as being of a poor quality.

The tutor had a single task of giving feedback on assignments uploaded by participants. Table 4 shows the number of assignments to which the tutor gave feedback in all seven sessions of the course. The tutor’s task was to give feedback to help the individual learners to revise their initial submissions of texts, and not for subsequent revised submissions. The comment by one participant [SF-1557] draws attention to the inadequacy of the tutor’s single feedback on submissions. She expected the tutor to check her revised submission prior to uploading it to the Final Copy Forumas revealed in this statement:

… the final stage, the very end of it, I don’t know whether you have checked the thing otherwise I wish if you have checked the final thing then it’s perfect like, after making the correction, we don’t know whether our corrections are correct even …to do the final copy as well. [SF-1557-Interview]

The findings reveal that the participants experienced several challenges that interfered with interaction and collaboration between participants in the online environment of the course. As respects the implementation of the rule element, participants found it challenging to adhere to all the rules. Three significant contradictions that emerged were related to the view that the rules were restrictive and did not give opportunity to interact with, and give feedback to, learners in other groups. The number of rules was excessive and conforming to four (4) rules was difficult. The third contradiction related to conformity to the rules being beyond the control of the subject.

Challenges were also present as respects the DoL in the online environment, the individual tasks, peer task and tutor task. The major challenges encountered were related to low participation in individual tasks. These included time constraints due to family and career commitments as well as poor language proficiency. Also, the lack of incentives, such as making the task compulsory and giving marks, adversely affected self-motivation. The challenges that affected interaction in the peer task were the lack of engagement or delayed engagement in the tasks. Additionally, the disparate language competency of participants caused some who were less proficient to refrain from commenting. Those who were less proficient in the English language did not know how to correct mistakes in their own writing. Also, those who were more proficient viewed others’ submissions as of a poor quality. The tutor task did not present much of a challenge.

The common contributory factors for the tensions within the two activity triangles (S-R-O) and (C-DoL-O) were: 1) time constraints, 2) disparate English language proficiency levels, and 3) motivation, which will be expanded on below.

Time constraints due to personal and institutional factors impinged on the level of interaction and participation in most activities, as well as the extent of feedback. This was observed within and between the Subject-Rules, and the Community-DoL of the two activity triangles. These results were endorsed by the interview responses. Time constraints due to personal factors were because the majority of participants were adult learners, who were employed with secular and domestic commitments. Balancing these multiple roles along with their studies was challenging (Quimby & O’Brien, 2004, Topham, 2015). Furthermore, these commitments impinged on the level of participation because time was required to think about what to say in order to contribute meaningfully to online DFs. These results are also supported by the findings in other studies (Chathurika, & Rajapaksha, 2017; Fung, 2004; Mason, 2011; Ng & Cheung, 2007; Yukselturk, 2010).

Time constraints due to institutional factors were related to the set rules and the number of activities included in the course. Many participants confirmed at the interviews that they felt that the rules were too many, and some found the procedures when engaging in the activities complex and time consuming. Also, the lack of peer responses and delay in responses in the DFs impinged on their time. Considerable time is also taken to read and respond to posts. The study by Beaudoin (2002) found that less visibly active students spent 7.6 hours on an average during a two-week period of online conferences reading the comments of others. They also spent another 2.2 hours writing comments. These hours were spent only for participation in discussion. In this present research, at each stage of the PA participants were required to engage in several tasks: individual, peer, individual and tutor tasks, reading messages, writing assignments and reflective journals. The responses to the interview reinforce the finding that the online course activities took more time and commitment than anticipated.

Disparate English language proficiency contributed to contradictions in the two activity triangles (S-R-O), (C-DoL-O). The findings revealed a close interrelationship between interaction, feedback and motivation; one can cause a reaction in another and vice versa. These were adversely affected by disparate English language proficiency, as confirmed by the interview responses. The findings also show that there was a significant relationship between language proficiency and online interaction, as endorsed in the study conducted by Leung (2013). In the present research, participants who were less proficient in the English language engaged minimally in individual and peer tasks in the assigned activities when they realised that others in their respective groups were more proficient. Some participants were de-motivated from engaging more fully in assigned activities especially in the latter phases of the course for the same reason. This was especially evident in the Editing and Proofreading session that required a higher level of language proficiency resulting in reduced feedback on peer submissions. These results corroborate with the findings by Gunawardena and Jayatilleke, (2014) in a study on online learning and cross-cultural e-mentoring which revealed that the participants with limited linguistic proficiency participated less, and therefore suggested that this limitation of these ESL learners be taken into consideration when designing online activities.

Both external and internal aspects of motivation contributed to the tension in the (S-R-O) and (C-DoL-O) activity triangles of the activity system of the Advanced Writing Skills course.

External factors adversely affected both interaction and engagement in the assigned activities, as well as feedback which was ascertained from the log file reports and confirmed by the interview responses. The interview responses reveal that the two primary reasons were the lack of incentives because no marks were allocated for engagement in the assigned activities, and the other was that engagement was not compulsory. This resulted in the participants circumventing rules and failing to contribute meaningfully to the assigned activities. A similar lack of incentive was noted in other studies (Aduayi-Akue, et al, 2017; Fung 2004; Lee & Brian, 2011). Conversely, studies conducted by Nandi et al (2011), attributed greater participation in the DFs because the tasks were made compulsory and marks were awarded. Garaus et al (2015) in their study recommend that giving online learners small rewards is beneficial as it gives opportunity for the learner to get feedback, which would not be possible if they did not submit their work and makes it possible to engage the learner in greater interaction, and does not take away their autonomy. Considering the findings of these studies with the results of the present research, it is evident that compulsory discussion forum assignments and allocation of marks would motivate students’ engagement in assigned activities.

The contradictions encountered in this study is in keeping with Foot’s (2014, p. 17), observation that contradictions are like “illuminating hinges” that give greater insight into the workings of an activity system and open up opportunities to develop the activity under consideration; viewing the interactions in the online environment enabled identification of the challenges faced by the learners, which need to be addressed to facilitate greater participation and interaction among participants.

In distilling the results of the study several key factors have contributed to decreased participation in the latter stages of the course. Foremost, was the constraint of time because most participants were adults with secular and domestic commitments. Next was the disparity in language proficiency levels of participants. Also, the rules imposed were too restrictive, excessive and beyond the control of the subjects. Yet another factor was the lack of incentives that affected motivation. These outcomes indicate that at an institutional level, consideration has to be given to the above factors in designing future online courses for ESL students.

Consideration could be given to extending the duration of the course, increasing the period between each session, thus giving more time for the completion of the online activities as well as imposing reasonable rules that are within the control of the subjects. Also providing motivation through rewards would be a strong incentive for greater engagement and interaction. To address the learners’ limited language proficiency, consideration could be given to design more optional online activities, such as quizzes and self-correction tasks, whereby the learners can readily improve their language competency.

This study reported on the application of Activity Theory’s principle of contradictions to analyse the challenges encountered by ESL learners in a blended learning writing course. The most significant challenges that interfered with interaction and collaboration among participants were the strict rules, and the number of rules that were required of the participants who were adult learners. These necessitated participants to devote considerable time to the activities. Also, the disparity in the level of English language proficiency affected adequate interaction; this together with the time constraints of the working adults, whose second language is English, impinged on the extent of interaction because gaining language proficiency needs time.

In this study AT with its principles of contradictions makes a significant contribution to the body of knowledge in terms of its use in examining online interactions in the field of blended-learning writing pedagogy. Further research could also be carried out to investigate interaction in the f2f component of a blended learning writing course and a comparison made of the challenges learners encounter in the f2f and online environments, which might yield further insight and widen the knowledge in the field of writing research.

Adas, D., & Bakir, A. (2013). Writing difficulties and new solutions: Blended learning as an approach to improve writing abilities. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 3(9), 254-266. https://staff-old.najah.edu/sites/default/files/28.pdf

Aduayi-Akue, J., Lotchi, K., Parveen, S., Onatsu, T. & Pehkonen-Elmi, E. (2017). Motivation of online learners. JAMK Open Access Online Magazines, Evolving Pedagogy — Greetings from Finland. https://verkkolehdet.jamk.fi/ev-peda/2017/01/25/motivation-of-online-learners/

Barab, S. A., Barnett, M., Yamagata-Lynch, L., Squire, K., & Keating, T. (2002). Using activity theory to understand the systemic tensions characterizing a technology-rich introductory astronomy course. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 9(2), 76-107. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327884mca0902_02

Baran, B., & Cagiltay, K. (2010). The dynamics of online communities in the activity theory framework. Educational Technology & Society, 13(4), 155-166. http://www.ifets.info/journals/13_4/14.pdf

Beaudoin, M. F. (2002). Learning or lurking? Tracking the “invisible” online student. Internet and Higher Education, 5, 147–155. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.505.5696&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Brine, J. W., & Franken, M. (2006). Students' perceptions of a selected aspect of a computer mediated academic writing program: An activity theory analysis. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 22(1), 21-38. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1305

Chathurika, P.R.D., & Rajapaksha, P.L.N. R. (2017). Learner’s perception on online learning in open and distance education mode in the diploma in early childhood and primary education, The Open University of Sri Lanka. International Journal of Scientific Research, 2(4), 42-52. http://journalijsr.com/content/2017/IJSR33.pdf

De Silva, R. (2014). Writing strategy instruction: Its impact on writing in a second language for academic purposes. Sage Journals. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814541738

Engeström, Y. (1999) Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R-L. Punamaki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit. http://lchc.ucsd.edu/mca/Paper/Engeström/Learning-by-Expanding.pdf

Ekundayo, S., Wang, W., & Andrade, A.D. (2012). The use of activity theory and its principle of contradictions to identify and analyse systemic tensions: The case of a Virtual University and its partners. Paper presented at Conference, CONF-IRM 2012 Proceedings, 33. http://aisel.aisnet.org/confirm2012/33

Ferriman, N. (2013). The impact of blended e-learning on undergraduate academic essay writing in English (L2). Computers & Education, 60(1), 243-253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.07.008

Fonseka, G. (2008). The teacher's role in achieving student empowerment through English. In D. Fernando, & D. Mendis, (Eds.), English for equality, employment and empowerment (pp. 27-37). Ceylon Printers Ltd.

Foot, K. A. (2014). Cultural-historical activity theory: Exploring a theory to inform practice and research, Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 24(3), 329-347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.831011

Fung, Y. Y. H. (2004) Collaborative online learning: Interaction patterns and limiting factors. Open Learning, 19, 135-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051042000224743

Garaus, C., Furtmuller, G., & Guttel, W. H. (2015). The hidden power of small rewards: The effects of insufficient external rewards on autonomous motivation to learn. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0284

Gedera, D. S. P., & Williams, P. J. (2013). Using Activity Theory to understand contradictions in an online university course facilitated by Moodle. International Journal of Information Technology & Computer Science, 10(1), 32-41.

Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Theory and practice of writing: An applied linguistic perspective. Longman.

Gunawardena, C.N., & Jayatilleke, B. G. (2014). Facilitating online learning and cross-cultural e-mentoring. Culture and Online Learning: Global Perspectives and Research, 67-68. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Illangakoon, S. R. (2011/2012). Identifying threshold vocabulary for academic study. In H. Ratwatte (Ed.), Vistas, Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 7 & 8, 141-159. Nawala, Sri Lanka: Open University of Sri Lanka.

Jamaldeen, F., Ekanayaka, Y., & Hewagamage, K. (2016). A theoretical approach to initiate mobile assisted language learning among school leavers and university students of Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of Mobile assisted Language Learning, Australasian Conference on Information Systems 2015. Adelaide.

Jones, C. (1999). The student from overseas and the British University. In C. Jones, J. Turner & B. Street (Eds.), Students writing in the university: Cultural and epistemological issues (pp. 37-56). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Kroll, B. (Ed.). (1990). Second language writing. Research insights for the classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Kumara, M.D.S.S. (2009). Compilation and linguistic analysis of a dedicated corpus for the Applied Sciences: Special focus on the spoken academic discourse of the applied sciences study programme of the Rajarata University of Sri Lanka. (Unpublished MA dissertation.) University of Kelaniya.

Lee, C. Hin, B. (2011). Effect of incentivized online activities on e-learning, The Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28, 211- 216.

Leung, S. (2013). English proficiency and participation in online discussion for learning. Paper presented at IADIS International Conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in Digital Age (CELDA 2013). Fort Worth, TX, Oct 22-24, 2013. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED562207.pdf

Liu, M. (2013). Blended Learning in a university EFL Writing Course: Description and evaluation. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(2), 301-309. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.2.301-309

Mason, R. B. (2011). Student engagement with, and participation in, an e-forum. Educational Technology & Society, 14(2), 258-268. http://196.21.61.18/bitstream/10321/2455/1/Mason_JETS_Vol14%232_Pg258-268_2011.pdf

Nandi, D., Hamilton, M., Harland, J., & Warburton, G. (2011). How active are students in online discussion forums? In J. Hamer & M. de Raadt (Eds.), Conferences in Research and Practice in Information Technology (CRPIT), 114. Proceedings in 13th Australasian Computing Education Conference (ACE2011), Australian Computer Society, Inc.

Ng, C. S. L., & Cheung, W. S. (2007). Comparing face to face, tutor led discussion and online discussion in the classroom. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(4). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1246

Palmquist, M., Kiefer, K., & Salahub, J. (2009). Sustaining (and growing) a pedagogical writing environment: An activity theory analysis. In D. N. DeVoss, H. A. McKee, & R. (D.) Selfe (Eds.), Technologies and sustainability. https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/tes/index2.html

Perera, K. (2006). Laying the foundations: Language planning in the ELTU. In H. Ratwatte, & S. Herath (Eds.), English in the multilingual environment (pp. 47-57). Open University of Sri Lanka.

Polio, C. (2001). Research methodology in second language writing: The case of text-based studies. T. Silva 7 P. Matsuda. (Eds.), On second language writing. (pp. 91-116). Erlbaum.

Pullenayegem, J.C.N., De Silva, K.R.M., & Jayatilleke, B.G., (2020) Open and distance learner engagement with online mediation tools: An activity theory analysis. Open Praxis, 2(4) 469-483. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.12.4.1129.

Quimby, J. L., & O'Brien, K. M. (2004). Predictors of student and career decision-making self-efficacy among nontraditional college women. The Career Development Quarterly, 52(4), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2004.tb00949.x

Raheem, R., & Ratwatte, H. (2001). Regional variations in student proficiency and its implications for language planning. In D. Hayes, Teaching English: Possibilities and opportunities. Selected papers from the 1st International Conference of the Sri Lanka English Language Teachers’ Association (pp. 23-36). Colombo, Sri Lanka: The British Council.

Ratwatte, H.V. (2005). Teaching in the learner’s second language: The OUSL context. Extended Abstract. Silver Jubilee OUSL Academic Sessions (pp. 92-100). Open University of Sri Lanka.

Raimes, A. (1985). An investigation of how ESL Students write. (Report No. FL 015 822). Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. (19th, New York, NY, April 9-14, 1985). (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 271 965). http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED271965.pdf

Shafiee, S., Koosha, M., & Afghari, A. (2015). CALL, Prewriting strategies, and EFL writing quantity. English Language Teaching, 8(2), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n2p170

Silva, T. (1990). Second language composition instruction: Developments, issues, and directions in ESL. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Second language writing research: Research insights for the classroom. (pp. 11-23). Cambridge University Press.

Sivaji, K. (2011). A study of the impact of direct and indirect error correction on undergraduate writing at the Faculty of Arts. (Master’s Thesis). University of Jaffna. The Open University of Sri Lanka digital repository. http://digital.lib.ou.ac.lk/docs/bitstream/701300122/527/1/Karunathevy%20Sivaji.pdf

Topham, P. (2015). Older adults in their first year at university: Challenges, resources and support. University of the West of England.

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

Yoon, S. Y., & Lee, C. H. (2010). The perspective and effectiveness of blended learning in L2 writing of Korean university students. Multimedia-Assisted Language Learning, 13(2), 177-204. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287640821_The_Perspectives_and_Effectiveness_of_Blended_Learning_in_L2_Writing_of_Korean_University_Students

Yukselturk, E. (2010). An investigation of factors affecting student participation level in an online discussion forum TOJET: The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 9(2) 24-32. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ897999.pdf

Zamel, V. (1983). The composing processes of advanced ESL students: Six case studies. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 165-187.

Authors:

Judy Pullenayegem is a senior lecturer and serves as the Director of the English for General Academic Purposes (EGAP) Programme at the Department of English Language Teaching (DELT) at the Open University of Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Open and Distance Learning, and Teaching English as a Second Language. She specializes in teaching English in the ESL context, in conventional, blended, and online courses. Her research interests include L2 writing and online teacher education in the Open and Distance Learning (ODL) context. Email: jcpul@ou.ac.lk

Radhika De Silva is a senior lecturer in Language Studies at the Open University of Sri Lanka. She holds a PhD in Language Education from University of Reading, UK. She has extensive ELT and teacher training experience. She teaches and mentors undergraduate and postgraduate level students. Her research interests include L2 writing, strategy instruction, EAP, language teacher education, language testing, and open and distance education. Email: krsil@ou.ac.lk

Gayathri Jayatilleke is a Professor in Educational Technology, and the Acting Director of the Centre for Educational Technology and Media (CETMe) of the Open University of Sri Lanka (OUSL). She holds a PhD in Educational Technology from the Open University, UK, a Master’s in Education and Development from the Institute of Education, University of London, UK and a B.Sc. (Natural Sciences) from the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. She has extensive experience as a teacher, researcher and a trainer in the field of Open and Distance Learning (ODL) and Educational Technology. Email: bgjay@ou.ac.lk

Cite this paper as: Pullenayegem, J., De Silva, R., & Jayatilleke, G. (2021). Contradictions in learner interactions in a blended-learning writing course: An activity theory analysis. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 327-345.