2021 VOL. 8, No. 1

Abstract: Over the last two decades research has indicated an unpleasant experience for the elderly with exemptions. An important question for this paper is whether the unpleasant exempted experience for the elderly in accessing health services is linked to illiteracy. Since illiteracy can affect how services are used and its results, the answer to this paper’s question could affect how health services are accessed and their associated outcomes. Policy implementors are operating without a solid knowledge of this relationship. The study used a mixed methods approach. Purposive random sampling was applied to select 879 elderly and was guided by research assistants in filling in the questionnaires. Also, purposive sampling was used to recruit 23 key informants. Results indicates a significant relationship between illiteracy and selected indicators of health service access: awareness, acceptability and adequacy. This paper argues for more training opportunities through non-formal programs among adults and communication capacity building among health providers based on the results of implementing the elderly exemption policy in Ubungo and Mbarali districts in Tanzania.

Keywords: literacy, exemption policy, health services access and elderly.

In Tanzania, the elderly health fee exemption policy was introduced to overcome the financial barrier in accessing health services among elderly people (URT, 2007). According to the National Ageing policy (2003), elderly people are men and women aged 60 and above. The government enacted the health fee exemption policy to enable the elderly who cannot afford the cost of health services to access health care in public health facilities. The enaction of the health fee exemption policy is guided by a cost sharing manual. The manual classifies the exempted elderly people into two categories. The first group comprises those who are living in extreme poverty; usually on relief funds under the Tanzania Social Action fund (TASAF). The elderly people who fall into this category are entitled to the full health fee exemption. The second category is the elderly who have substantial income but cannot afford to cover the entire costs of health services and, therefore, are subjected to a partial health fee exemption (exemption with subsidisation).

The policy allows the elderly to seek treatment from the grassroots level to the national level through a referral system. The Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MHCDGEC) is the policy custodian that oversees policy implementations at the national level. While the local government authorities, through the social welfare and health departments, implement the policy at the district and grassroots levels by systematically coordinating the identification of beneficiaries and grant exemptions to eligible elderly people to utilise health services.

To create awareness of the health fee exemption policy, the Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (formerly the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare) use an advocacy approach to raise stakeholders’ awareness on various health issues, such as health fee exemption policy (MHSW,2010). The advocacy materials include leaflets, banners, billboards, fliers, periodical publications and electronic media, such as radio and television programs. However, according to Munishi (2010) and Nzali (2016) there is low awareness of health fee exemption policy due to lack of a well-organised plan to disseminate information, and a weak monitoring and evaluation framework. This implies that the public is not adequately informed about the policy. Furthermore, Nzali (2016) explains that the public, especially the elderly, have limited access to sources of information, such as brochures and noticeboards, which are the main sources of information. It is worth noting that most elderly people have limited or no reading skills. Another factor to consider is that local community leaders at the grassroots level provide insufficient information about the policy during community meetings. Therefore, this hinders awareness about health fee exemption policy among the elderly community.

Literacy is a globally advocated concept and yet lacks a global general definition. The simplest form of literacy is the ability to read and write (Keefe & Copeland, 2011). According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) literacy can be measured based on individual abilities to identify, interpret, create and communicate signs in digital media and text. Moreover, complexity in defining literacy might increase from how reading and writing skills have been best acquired (Mlekwa, 1994; Keefe & Copeland, 2011). This implies that the skills can be gauged from a poor level (illiterate) to a sufficient level (literate). The furthest complexity might be how the sufficiently well-acquired reading and writing skills are applied to further knowledge in a certain field of study that produces a certain level of pre-determined outcome. For example, in the field of health studies “health literacy” does not measure ability to read and write health concepts but the ability to critically weigh and manipulate the implications on relationships among meaningful determinants of health. This implies the ability to put into use efficiently and productively certain knowledge and not just the ability to barely read or write. Therefore, a measure of literacy reflects demands for skills around an individual’s environment and the scope/level to which a skill has been mastered. However, factors such as culture, availability of resources that advocate learning — including schools, technology and individual willingness) influence literacy acquisition.

In Tanzania literacy is defined in the context of one’s mastery of the abilities to read, write and understand numeracy (Mlekwa, 1994; IAE, 2011). In recent years the literacy of older adults has been declining compared to the 1970s and 80s. Data from the Education Sector Development Plan (ESDP) 2016/17-2020/21 indicates that nearly a quarter of adults are illiterate (URT, 2018). Adult and non-formal education (ANFE) contributed significantly to the previously recorded highest literacy levels (IAE, 2011; Hall, 2020). The Institute of Adult Education (IAE) established in 1972 is a pillar of ANFE. It regulates provision of ANFE and offer various awareness raising programs across health services, agriculture, the citizenry (through various methodologies including peer-to-peer education), multimedia, publications and electronic media (radio and television). It is worth noting that, the public sector policy shift from service provision to the liberal economy in 1980s and 90s exposed the ANFE to funding vulnerabilities.

Johnson (1991) defines health services access as the degree to which individuals or groups are able to obtain the needed services from the health systems. This implies that access is gaining entry into health facilities and actually utilizing health services. Additionally, Saurman (2016), argues that obtaining the needed service from health systems implies interaction between the supply side (health service provider) and the demand side (elderly people, in this case). Penchinsky and Thomas provide a 5 “A”Indicators for measuring access to health services: Availability, Accessibility, Affordability, Adequacy and Acceptability.

Availability implies the state of a health facility to have sufficient services and resources that meet patients’ needs in relation to health services. It is important to observe that health facilities are ranked into levels: lower (dispensaries) and upper level (National Referral Hospital). However, most elderly people are at the grassroots level, which hosts most dispensaries and is limited to offering primary health services. This denies the elderly access to specialised health services, especially for non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure. This means that the elderly have to travel longer distances to seek specialised health care. In addition to that, most public health facilities experience a deficit of medical supplies and lack specialised health care providers (geriatricians). This, as well, discourages the elderly from seeking health service as it affects the quality of service received.

Another consideration in measuring access to health services is accessibility, which implies the distance from the health facility to the service user (elderly people). For instance, in Tanzania the desirable distance is a 5 km radius (URT, 2007). However, most health facilities in rural areas are within a radius of 5-10 km (Munishi, 2010). Longer distance tends to discourage the elderly from seeking health services.

Another measure is affordability, which implies monetary and non-monetary costs incurred by service providers and patients to obtain health services. For the case of exempted elderly people, the monetary cost might include an indirect cost, such as the cost of transport and foregone revenue. Non-monetary costs include waiting time. Usually, long hours waiting discourages elderly people from accessing health services.

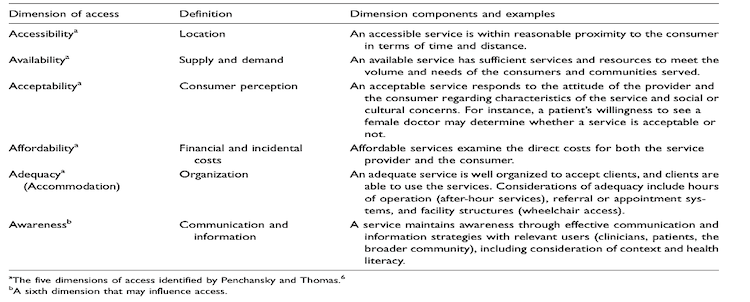

The last, but not least, measure of access in Penchinsky and Thomas’ 5 “A” Indicators is adequacy, which implies organization of services in a manner that is compatible with the user’s lifestyle. Moreover, Saurman (2016) modified Penchinsky and Thomas’ 5 “A” Indicators by adding Awareness, thus, improving these Indicators to 6 “A” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Saurman’s modified 6 “A” Indicators of access to health services.

Source: Saurman (2016)

Awareness connotes application of strategies and channels of communication to enrich understanding of procedures and services for obtaining healthcare. Most often elderly people that are eligible for exemption end up not benefiting because they are not aware of the available services and the procedures. In some cases, the medium used by policy implementors to communicate policy information might be less accessible to elderly people. The most preferable way to disseminate information at local levels is the noticeboard. The majority of the elderly have limited locomotive abilities and a high number are illiterate, especially in rural areas.

Shrestha, (2010) further argued that, while each factor is independent, yet, in a way, they are somehow interconnected. As noted by Shrestha, the application of any number of factors in measuring access to health services should not only reflect the interest but also the context of the study. Moreover, the author classified the factors into two groups. The first four factors (with addition of “Awareness”) signify potential access to health services while the last two “Adequacy and Acceptability” signify realised access, which is actual utilization of health services (Shrestha, 2010).

From 5 “As”, this paper has selected only 3 “As” to form the framework in measuring health services access in the Ubungo and Mbarali districts. The selected 3 “As” are Awareness (elderly people decide on when to seek health services, the source of policy related information among elderly, their policy awareness and understanding), Adequacy (the elderly’s choice of health facility and the last visited health facility) and Acceptability, which aims at assessing elderly people’s relaxed engagement with health workers, perceived stigma and satisfaction with health services.As explained by Sandiford et al (1995) illiteracy widens the gap in information searching and decision making that, in turn, determines if and how services are approached. For instance, Sandiford et al (1995) points out that if access to health services were minimal, a child of a literate mother would have more chances of obtaining health care compared to that of an illiterate mother. Further, Kumeh et al (2020), noted that there is positive relationship between the literacy of a mother and child’s malnutrition status. This means that regardless of asymmetry in the supply of public goods or services illiterate individuals have significantly less chances of benefiting.

According to Wedin (2008), literacy can be used as gatekeeper in social services. This implies it is most likely for illiterates to be excluded from the official discourse on services. For example, for an elderly person to acquire an exemption identifier card there are written guidelines. This means that only those that can read will obtain first-hand information. Thus, those who can’t read might either receive such information through word of mouth, which is prone to distortion, or might not receive it at all. In most cases this tends to reduce the confidence of illiterate people to pursue information and obtain exemption identifier cards.

This study used a mixed-method approach with multiple case-study design. The design was useful in comparing and contrasting findings between the Mbarali and Ubungo districts. It used a cross-sectional approach to collect data from July 2019 to September 2019. Multi-stage sampling was applied, and purposeful sampling was used to select elderly people aged 60 years and above who are beneficiaries of the exemption policy. Thereafter, purposive random sampling was applied to select 879 elderly people who were guided by research assistants in filling in the questionnaires. Respondents were asked if they could read and write in Swahili for the purpose of determining the level of guidance needed in reviewing and signing participants’ consent form and filling in their questionnaire. Also, purposive sampling was used to recruit 23 key informants who were comprised of policy makers, district health managers, district social welfare officers and health workers in public health facilities (dispensaries, health centers and the district hospital), district social welfare officers, local community leaders, elderly committee members and stakeholders from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs).

Quantitative data was collected through survey questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered by interviewing respondents using mobile technology data collection software “Kobocollect”. Data was downloaded, cleaned and analyzed. Descriptive statistics analysis was done using STATA 14 software. The analysis of data was guided by the three purposely selected indicators of health services access. Logit regression analysis was applied to determine the level of association between self-reported literacy status and indicators of health service access. These indicators were used to form categories of the results. The indicators were awareness, decision on when to seek care, source of policy related to information, policy awareness, and policy understanding. Other indicators were adequacy; rationale for choosing health facility and reported last visit to a health facility level. Indicators of acceptability, engagement with health workers, perceived stigma, and satisfaction with health services were also used to form the categories.

Furthermore, qualitative data was collected through in-depth interviews. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes and were conducted in Kiswahili and recorded. Verbatim transcription of interview materials was done and then transcripts were translated to English by a language professional. Data was analyzed using NVIVO 12 software and coded into themes. The findings are presented in the following section.

Results on literacy status among elderly surveyed in this study indicate that the illiteracy rate among the elderly is higher in Mbarali district, standing at 58.8% (325) compared to Ubungo district, which is 25.9% (113). The literacy status established by this study in two districts resulted from respondents’ self-reported ability to read. However, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, the elderly national illiteracy rate is 51.9% (URT, 2012).

The study observed that 71.5% of the illiterate elderly seek health services when they are seriously ill, against 23% of the literate elderly. It noted that the literate elderly seek health services even with a mild illness (see Table 1). As stated by one health worker, “In spite of being exempted from paying for cost of care, most elderly often come to seek health care when the condition has developed extreme health repercussion” (KII #03-Health Worker).

Table 1: Elderly reported experience of when the decision to seek health services was made

Across Districts |

||||

Source of Policy Related Information |

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Severe illness |

236 |

54% |

128 |

23% |

I do regular checkups |

96 |

22% |

103 |

19% |

Mild illness |

106 |

24% |

318 |

58% |

Total |

438 |

100% |

549 |

100% |

Ubungo District |

||||

Source of Policy Related Information |

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Severe illness |

94 |

83% |

118 |

48% |

I do regular checkups |

14 |

12% |

27 |

8% |

Mild illness |

5 |

4% |

178 |

55% |

Total |

113 |

100% |

323 |

100% |

Mbarali District |

||||

Source of Policy Related Information |

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Severe illness |

142 |

44% |

10 |

4% |

I do regular checkups |

82 |

25% |

76 |

34% |

Mild illness |

101 |

31% |

140 |

62% |

Total |

325 |

100% |

226 |

100% |

Source: Research 2019.

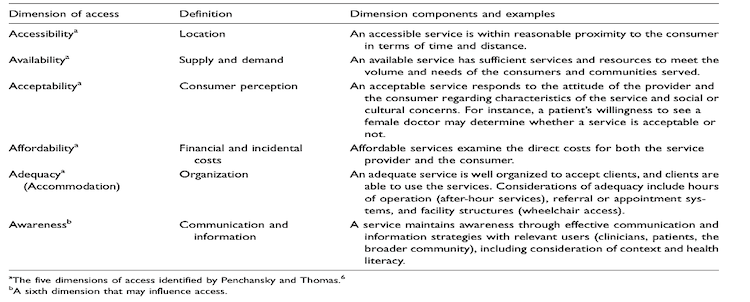

It is beneficial to identify the strongest medium for transmitting policy related information. Most often the medium tends to affect the level of policy awareness and understanding. From the findings across study districts, it was observed that word of mouth from peers is a major source of policy information among the illiterate elderly. While the literate elderly highly relied on local government offices to receive policy information. However, media, such as brochures, were also used as source of information, although, at minimal levels, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Elderly self-reported source of policy related information

Source: Research 2019

Given the fact that information is power, it was crucial to determine the level of awareness about policy related information among the elderly. The findings show that awareness among the literate elderly is higher, standing at 80% compared to 30% of the illiterate elderly as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Elderly self-reported policy awareness levels

Across Districts |

||||

|

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Awareness Levels |

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

Very High |

6 |

2% |

97 |

18% |

High |

13 |

4% |

146 |

27% |

Moderate |

79 |

24% |

193 |

35% |

Very low |

96 |

29% |

74 |

13% |

Low |

136 |

41% |

39 |

7% |

Total |

330 |

100% |

549 |

100% |

Ubungo District |

||||

|

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Awareness Levels |

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

Very High |

4 |

4% |

53 |

16% |

High |

6 |

5% |

87 |

27% |

Moderate |

37 |

33% |

113 |

35% |

Very low |

24 |

21% |

28 |

9% |

Low |

42 |

37% |

42 |

13% |

Total |

113 |

100% |

323 |

100% |

Mbarali District |

||||

|

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Awareness Levels |

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

Very High |

2 |

1% |

37 |

16% |

High |

7 |

3% |

78 |

35% |

Moderate |

42 |

19% |

47 |

21% |

Very low |

72 |

33% |

28 |

12% |

Low |

94 |

43% |

36 |

16% |

Total |

217 |

100% |

226 |

100% |

Source: Research 2019

The power of information to act and create impact relies on the correctness of information at hand. When asked to explain the criteria of policy beneficiaries, the study established that across study districts 6.5% (13) of the illiterate elderly surveyed understood the health fee exemption policy, against 19% of surveyed literate elders. However, when asked to explain the exemption criterion for policy beneficiaries’, none of the surveyed Illiterate elderly were able to correctly cite the policy criterion. On the other hand, surprisingly, regardless of their self-reported level of policy understanding as indicated in Table 3, 17 (3.4%) and 2 (1.7%) of the literate elderly from Ubungo and Mbarali districts, respectively, managed to explain correctly the health fee exemption policy criteria.

Table 3: Elderly self-reported policy understanding levels

Across Study Districts |

||||

Understanding levels |

Illiterate Elderly |

Literate Elderly |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

I understand very well |

2 |

1% |

34 |

7% |

I understand |

11 |

5% |

61 |

12% |

Moderate |

52 |

25% |

36 |

7% |

I don’t understand |

96 |

45% |

148 |

30% |

I don’t understand completely |

50 |

24% |

214 |

43% |

Total |

211 |

100% |

493 |

100% |

Ubungo District |

||||

Understanding levels |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

I understand very well |

3 |

3% |

26 |

12% |

I understand |

11 |

10% |

34 |

16% |

Moderate |

23 |

20% |

36 |

17% |

I don’t understand |

18 |

16% |

114 |

54% |

I don’t understand completely |

58 |

51% |

1 |

0% |

Total |

113 |

100% |

211 |

100% |

Mbarali District |

||||

Understanding levels |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

I understand very well |

2 |

1% |

5 |

4% |

I understand |

11 |

5% |

16 |

13% |

Moderate |

16 |

8% |

13 |

11% |

I don’t understand |

96 |

45% |

16 |

13% |

I don’t understand completely |

86 |

41% |

69 |

58% |

Total |

211 |

100% |

119 |

100% |

Source: Research 2019

Although the majority of the elderly had a misconception about the policy, one of them from Ubungo district correctly explained the policy by saying, “the policy pardons poor elderly who cannot afford to pay for health fee” (SRI #149-Illiterate Urban). On the contrary, the majority of those who were unable to explain the policy criterion had the following to say, “the policy pardons all elderly aged 60 and above to pay for health services” (SRI #232-Illiterate Rural).Another misconception among the elderly about the policy criterion is “every elderly with elderly identity card should receive health services without paying” (SRI #16-Literate Urban). From the evidence, low levels of understanding the policy at the local level are influenced by a lack of proper documented policy information. As stated by one community leader, “I haven’t come across any physical policy document. I am told to tell elderly that they have to register and be exempted from paying health fee.” (KII #01-Community Leader).

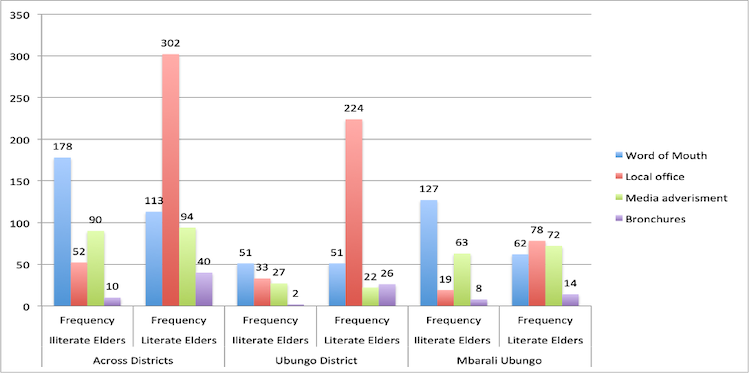

The findings show that the illiterate elderly’s choice of health services is largely influenced by the proximity of health facilities to their homes. However, literate elderly are more likely to choose health facilities based on the service offered (see Figure 2). “I did not go the district hospital in spite of being referred there, I cannot afford the travel cost”.

In addition to that, the national health system ranking of health facilities pre-determines the kind of services that can be accessed in certain level facilities as pointed to by one quality assurance expert, “elderly are prone to non-communicable diseases. Our national health system has categorised such treatment as specialised service. Such services can be accessed at least from district hospital level and above.” (KII #05-National Level Policy).

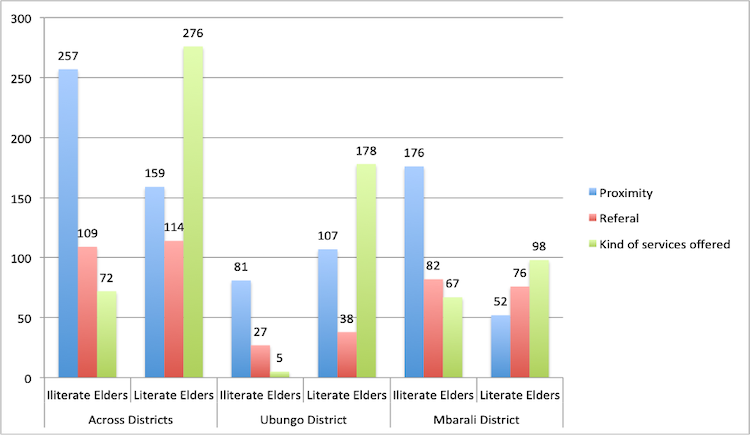

Figure 3: Elderly Self-reported behavior in selection of health facility

Source: Research 2019

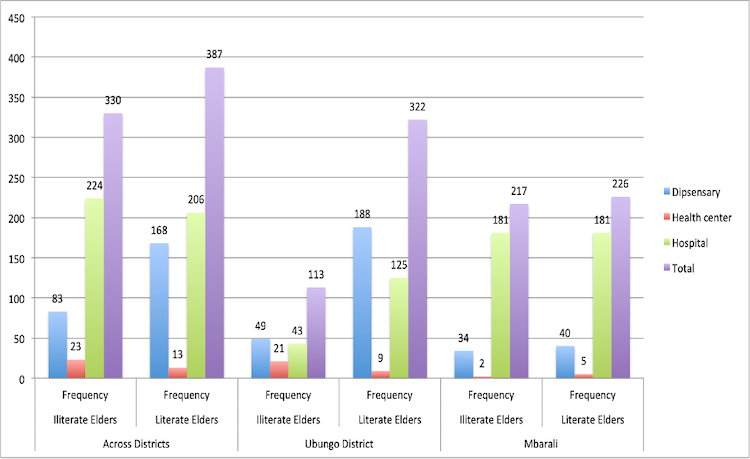

Across study districts, when asked about their last visit to a health facility, 68% of the illiterate and 53% of the literate elderly indicated that they had visited a hospital level facility. On the other hand, in the Ubungo district, 58% of the literate and 43% of the illiterate elderly had visited the dispensary level facilities (see Figure 3). “I usually go the district hospital, but when I wake up that day I was not feeling well and had no money. That’s why I went to our village dispensary”.

The study noted that there is a strong relationship between the elderly visiting a dispensary level facility and elderly complaints of unmet health service needs as evidenced in the following extract from one of the respondents: “... majority of elderly people suffer from non-communicable diseases such as diabetes. But they visit grassroots dispensaries for treatment of such condition. As a result, they complain being denied proper treatment” (KII #02-District Health Manager).

Figure 4: Elderly reported last visited health facility level

Source: Research 2019

Engagement with Health Workers

The findings of the study show that 65.4% of the literate elderly were comfortable when engaging with health workers, compared to 35.7% of the illiterate elderly. One elderly person said, “I have eyesight problem. I was asked to read the signs and I couldn’t. Though that lady (a nurse) try something else to evaluate if I could see at different intervals, my mind was not there. I couldn’t focus I was thinking of the embarrassment”.

However, in the Ubungo district, the majority of both literate (64.3%) and illiterate (63.7%) elderly were comfortable when dealing with health workers. Moreover, in the Mbarali district, the majority of the illiterate elderly (67%) indicated that they were more likely to feel high tension when engaging with health workers (see Table 4).

Though when they give medication they explain me thoroughly on timing when to take medication. Due to old age I have become forgetful, when I have several medication I get confused and sometime if I feel relief I stop taking them. I become so worried on if the doctors asked how I sed my previous medication.

The study observed that some patients tend to experience a natural phobia with a hospital environment. As stated by one key informant, “I know some patients feel a bit intimidated by [the] hospital environment. Though in reality they shouldn’t. I think it’s just a natural phobia.” (KII #04-Health Worker)

Table 4: Elderly perceptions on their encounter with health workers

Across Districts |

||||

State of mind when engaging health worker |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very comfortable |

36 |

11% |

193 |

35% |

Comfortable |

82 |

25% |

166 |

30% |

Am not sure |

10 |

3% |

37 |

7% |

Uncomfortable |

96 |

29% |

104 |

19% |

Very uncomfortable |

106 |

32% |

49 |

9% |

Total |

330 |

100% |

549 |

100% |

Ubungo District |

||||

State of mind when engaging health worker |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very comfortable |

12 |

11% |

102 |

32% |

Comfortable |

52 |

46% |

106 |

33% |

Am not sure |

4 |

4% |

18 |

6% |

Uncomfortable |

24 |

21% |

76 |

24% |

Very uncomfortable |

21 |

19% |

21 |

7% |

Total |

113 |

100% |

323 |

100% |

Mbarali District |

||||

State of mind when engaging health worker |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very comfortable |

24 |

11% |

91 |

40% |

Comfortable |

30 |

14% |

60 |

27% |

Am not sure |

6 |

3% |

19 |

8% |

Uncomfortable |

72 |

33% |

28 |

12% |

Very uncomfortable |

85 |

39% |

28 |

12% |

Total |

217 |

100% |

226 |

100% |

Source: Research 2019

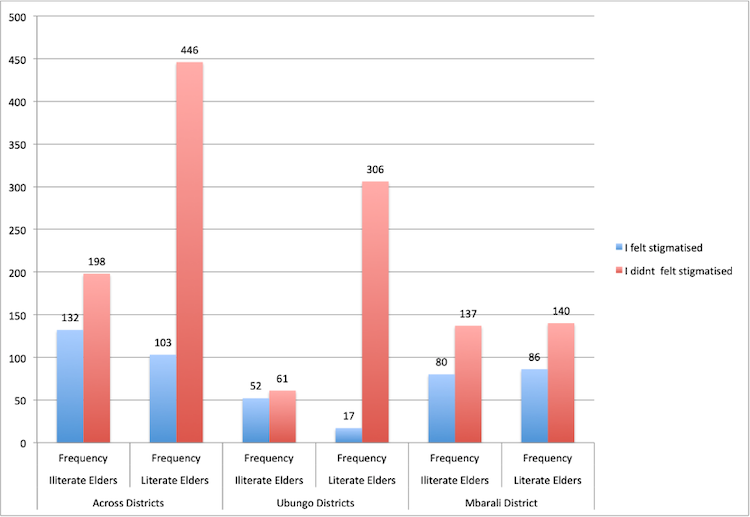

From the findings of the study across the districts, both literate (81%) and illiterate (60%) elderly noted that they did not experience stigma when dealing with health workers in public health facilities. However, in the Ubungo district, 46% of the illiterate elderly expressed their experience of being stigmatised by health workers at public health facilities, against 5% of the literate elderly. There was a similar trend in the Mbarali district, with 37% of the illiterate elderly experiencing stigma, compared to 38% of the literate elderly, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 5: Elderly self-reported perceptions on stigma during the last encounter with health workers

Source: Research 2019

The findings across the districts indicate that 70% of the literate and 69% of the illiterate elderly were satisfied with the health services they received in public health facilities. For example, in the Ubungo district, 58% of the literate elderly were satisfied with the health services they received during their last visit to a public health facility. On the other hand, the study noted that 76% of the literate and 78% of the illiterate in Mbarali district were satisfied with the health services they received (see Table 5).

Table 5: Elderly self-reported perceived satisfaction with health services received

Across Districts |

||||

Satisfaction with Health Services Received |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very Dissatisfied |

33 |

10% |

117 |

21% |

Dissatisfied |

68 |

48% |

48 |

9% |

Moderate |

14 |

4% |

24 |

4% |

Satisfied |

152 |

46% |

278 |

51% |

Very Satisfied |

63 |

19% |

82 |

15% |

Total |

330 |

100% |

549 |

100% |

Ubungo District |

||||

Satisfaction with Health Services Received |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very Dissatisfied |

16 |

14% |

102 |

42% |

Dissatisfied |

49 |

43% |

32 |

10% |

Moderate |

2 |

2% |

1 |

0% |

Satisfied |

45 |

40% |

182 |

56% |

Very Satisfied |

1 |

1% |

6 |

2% |

Total |

113 |

100% |

323 |

100% |

Mbarali District |

||||

Satisfaction with Health Services Received |

Illiterate Elders |

Literate Elders |

||

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Very Dissatisfied |

17 |

8% |

15 |

7% |

Dissatisfied |

19 |

9% |

16 |

7% |

Moderate |

12 |

6% |

23 |

10% |

Satisfied |

107 |

49% |

96 |

42% |

Very Satisfied |

62 |

29% |

76 |

34% |

Total |

217 |

100% |

226 |

100% |

Source: Research 2019

Over the years, access to exempted health services among the financially vulnerable elderly has improved in Tanzania, especially after the introduction of identification cards. However, satisfaction of the provision of health services remains questionable. As indicated in the study, the elderly population is less satisfied with the services. This is mainly due to weak infrastructure, an inadequate supply of drugs, the attitude and skills of health workers and lack of access to information. However, results indicate that the intensity of factors that limited health services access in the Ubungo and Mbarali districts were higher among the illiterate compared to the literate elderly. On awareness, the illiterate elderly decide to seek care only when seriously ill. The study shows that the inability to read intensifies health illiteracy and increases the likelihood of seeking healthcare at the late stages of diseases. As DeWalt et al (2004) observed, the illiterate individuals are more likely to have late diagnoses of diseases that result in irreversible damage. In addition to that, the study showed that the illiterate elderly highly relied on word of mouth as a major source of policy information. This implies that they have limited abilities for searching information, and their knowledge of policy information relies on someone else’s knowledge, which might have been distorted. Further, the illiterate elderly’s levels of policy awareness and understanding proves that they received distorted policy information.

On the adequacy measure, the illiterate elderly’s choice of health facility was not compatible with their health needs as they were more likely to visit a health facility due to its proximity. Thus, the majority of the elderly visited dispensaries regardless of the seriousness of their illness. This implies that the majority of elderly people that visited dispensaries couldn’t receive treatment for non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes. Moreover, this finding signifies the elderly’s complaints about the shortage of medical supplies at lower-level health facilities. As DeWalt et al, (2004) observed, there is a significant relationship between reading abilities and individuals’ knowledge of health services. The study reported those with reading abilities to have more knowledge of health services outcome. This implies that with the advantage of informed decision they might have more chances of locating compatible health facilities.

On the acceptability measure, the illiterate elderly felt higher tension when engaging with health workers. This implies that the quality of information shared with health workers (physicians) was compromised or, rather, insufficient. As a result, some health conditions might go undiagnosed if not well captured during consultation. In addition to that, the illiterate elderly were perceived to be more stigmatised by health workers than literate ones when receiving health services in the same facilities. This implies that the patient-physician relationship is less friendly. However, studies conducted by Nzali (2016), and Sanga (2013), indicate that health workers lack skills to attend to older adults. This implies that the quality of services offered to the elderly by health workers is not sufficient. Further, the illiterate reported a higher dissatisfaction with health services. The implication here is that the processes and treatment obtained in public health facilities needs improvement.

From the above examination of findings, it is rational to conclude that illiteracy affects the experience of exempted elderly people in accessing health policy benefits. This study recommends the following actions for improving the elderly experience in access to and utilization of health services in a policy context.

This study serves as the first work of which the author is aware that assessed the interplay among factors on the demand side for health services access within a health services safety net policy. The author suggests two main directions for further research. First, a broader study covering more districts to further elucidate illiteracy impact on health services access. Second, a randomised study that would be crucial to confirm that the negative results on determinants of health services access found in this study were indeed casually related to illiteracy.

DeWalt, D. A. et al (2004). “Literacy and health outcomes: A systematic review of the literature,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(12), pp. 1228-1239. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x.

Hall, B. L. (2020). Elimu Haina Mwisho: Mwalimu Nyerere ’ s vision of adult education. Papers in Education and Development, 38(38), 1-14.

IAE (2011). Report on 50 years of Independence (1961-2011) and future prospects of the next 50 years. Dar es Salaam.

Johnson, C. (1991). Access to health care in America. Journal of the National Medical Association. doi:10.5860/choice.31-0970.

Kumeh, O. W. et al (2020). Literacy is power: Structural drivers of child malnutrition in rural Liberia. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention and Health, 3(2). doi:10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000140.

Mlekwa, V. M. (1994). Contribution of literacy training to development in the context of Tanzania: Emerging issues and research implications. UTAFITI, 1(1).

MHSW (2010). Regional Referral Health Management Newsletter: Policy dissemination, a top gear for health sector reform in Tanzania, (3), 1-8.

Munishi, V. (2010). Implementation of exemption and waiver mechanism in Tanzania: Success and challenges.

Nzali, A. S. (2016). Determinants of access to free health services by the elderly in Iringa and Makete Districts, Tanzania. http://41.73.194.142:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/2053.

Sandiford, P. et al (1995). The impact of women’s literacy on child health and its interaction with access to health services. Population Studies, 49(1), 5-17. doi:10.1080/0032472031000148216.

Sanga, G. S. (2013). Challenges facing elderly people in accessing health services in Government Health Facilities in Moshi Municipality Area. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 53(9), 1689-1699. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Saurman, E. (2016). Improving access: Modifying Penchansky and Thomas’s theory of access. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 21(1), 36-39. doi: 10.1177/1355819615600001.

Shrestha, J. (2010). Evaluation of access to primary healthcare. (Unpublished thesis.) International Institute of Geo-Information Science.

Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Literacy and education monograph. https://www.nbs.go.tz/nbs/takwimu/census2012/Literacy_and_Education_Monograph.zip

United Republic of Tanzania (2003). National Ageing Policy. Ministry of Labor, Youth, Development and Sports.

United Republic of Tanzania (2007). National Health Policy. Ministry of Health.

United Republic of Tanzania (2018). Education sector development plan (2016/17-2020/21). Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 246. https://www.globalpartnership.org/sites/default/files/2019-04-gpe-tanzania-esp.pdf.

Wedin, Å. (2008). Literacy and power: The cases of Tanzania and Rwanda. International Journal of Educational Development, 1(6), 754-763. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2007.09.006.

Author:

Joshua Edward is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Dar es Salaam. Currently, he holds a teaching position at the Institute of Adult Education. Previously, he worked in the NGO sector as a monitoring, evaluation, research and learning expert. Email: joshuaedward2020@gmail.com

Cite this paper as: Edward, J. (2021). Interplay between literacy and health services access: The case of elderly exemption beneficiaries in Tanzania. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(1), 129-145.