2020 VOL. 7, No. 3

Abstract: Fifty-three percent of Grade 4 learners cannot read for meaning in low- and middle-income countries despite an investment of between 33-49% of education expenditure on primary education. Teaching children to read in the early grades is fundamental to building resilient education systems, as the ability to read early in life is a great predictor for education success, and will minimise learning loss during education emergencies similar to COVID-19 school closures, for children who can read for meaning can carry on learning outside of school buildings. Further, the predicted financing gaps in the next few years, as a result of COVID-19, will require governments to utilise limited financial resources effectively and efficiently by implementing literacy programmes proven to be impactful, using financial instruments like outcomes-based contracting that can mobilise and coordinate non-traditional educational finance and incentivise service providers to improve results by paying for achievement of agreed outcomes.

Keywords: education outcomes, early grade literacy, outcomes-based contracting.

COVID-19 has further exacerbated already existing education inequalities globally as financial demands for health and safety are imposing pressures on education budgets. Moreover, low- and middle-income countries reliant mostly on the fiscus as well as official development assistance (ODA) will experience greater pressure as these sources of funding will contract due to the effects of COVID-19. As such, governments need to review their financing mechanisms as well as utilisation of available funding by improving effectiveness and efficiency (World Bank, 2019a).

This paper advocates for the adoption of outcomes-based contracting to address poor early grade literacy in low- and middle-income countries by arguing that poor literacy is resulting in ineffective and inefficient education systems. We explore early grade literacy outcomes among selected countries where data is available, juxtaposing this with per learner education expenditure at the primary level for each country to show how expenditure is not commensurate with outcomes. The paper moves from a broad mapping of literacy outcomes and expenditure data among selected countries and zooms in on South Africa, where a historical overview of South Africa’s performance in international and regional benchmark tests is provided, followed by a discussion of interventions to improve early grade literacy and their effects. The paper concludes with a consideration of the potential of outcomes-based contracting (OBC) in improving early grade literacy to unlock children’s potential to succeed in school, not only in South Africa but also among resource-constrained low- and middle-income countries.

The World Bank reports that there are still 260 million children out of school and of those who are in school, many do not develop the fundamental skills which should lay the foundation of all future learning, affecting the trajectory of their future lives. Without the necessary human capital they cannot forge ahead and build successful livelihoods (World Bank, 2019b). The World Bank cites the poor quality of education and resultant poor educational outcomes as the root causes for the deficit in human capital.1

A fundamental skill that learners should develop early in school is literacy, as it unlocks learning in all subject areas (Spaull & Pretorius, 2019; Spaull, 2019a; Spaull, van der Berg, Wills, Gustafsson & Kotzé, 2016; World Bank, 2019b) and is critical for the attainment of future educational or social benefits (Cunha et al, 2006; Heckman & Masterov, 2007). Yet, staggering percentages of children are not learning to read proficiently by the age of 10, a phenomenon which the World Bank and the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics have termed “Learning Poverty” (World Bank, 2019a). The World Bank (2019a) postulates that children who cannot read are likely to drop out of school and equal opportunity to access better socio-economic possibilities is diminished for them.

The most recent data2 from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), an international comparative assessment that measures student learning in reading every five years since 2001, reveals that fewer than 40% of learners in participating African countries achieved the Low International Benchmark and barely any achieved the Advanced International Benchmark (Howie et al, 2017). Whilst it is easy to assume that a higher expenditure on education will result in improved learning outcomes, this is not always the case as shown by Boateng (2014). There is limited evidence to support the notion that increased expenditure will result in higher educational outcomes. Mlachila and Moeletsi (2019) as well as Jansen and Amsterdam (2006) emphasise spending the given allocations in an efficient manner, rather than increasing levels of expenditure.

In addition, as indicated in Table 1, some countries spend less per child, but attain better outcomes than countries spending more per learner.

Table 1: Reading Proficiency and Primary Education Expenditure

Country |

% children who cannot read for meaning at age 103 |

% children below minimum proficiency level |

Primary school expenditure per child USD)4 |

Botswana |

48% |

44%*5 |

1,620 |

Cameroon |

77% |

76%* |

196 |

Mauritius |

40% |

38%**6 |

3,480 |

South Africa |

80% |

78%***7 |

2,416 |

Uganda |

83% |

81%* |

99 |

Bangladesh |

57% |

55%** |

249 |

India |

55% |

54%** |

481 |

Malaysia |

13% |

12%* |

4,842 |

Pakistan |

75% |

65%*** |

372 |

Singapore |

3% |

3%*** |

16,021 |

Sri Lanka |

15% |

14%*** |

915 |

Finland |

3% |

2% |

9,485 |

Ireland |

2% |

2% |

8,334 |

Cameroon spends 196USD per learner at the primary level, and 77% of learners cannot read for meaning by age 10. South Africa on the other hand spends over 12 times the amount that Cameroon does (2,416USD per learner), and yet 80% of learners in South Africa cannot read for meaning by age 10, thus, learning poverty is higher in South Africa compared to Cameroon. Conversely, Botswana’s per learner expenditure is 1,620USD, lower than that of South Africa’s, yet only 44% of learners in Botswana cannot read for meaning by age 10. In other developing countries like India and Bangladesh, the expenditure per learner at the primary school level is 481USD and 249USD, respectively, yet their learning poverty rates are lower than South Africa’s, with only 55% of Indian learners and 57% of Bangladeshi learners aged 10 unable to read for meaning by age 10.

Table 1 also shows that Singapore spends the most per primary school learner (16,021USD) and has very low learning poverty rates — only three percent of learners cannot read for meaning at 10, and only three percent of learners read below the minimum proficiency level. However, Finland and Ireland are able to achieve similar results with lower expenditure — Ireland spends 8,334USD per primary school learner and learning poverty rates are lower than in Singapore.

The analysis above suggests that there is some inefficiency in education systems among both high- and low-expenditure countries based on the results they are getting from their inputs, relative to expenditures by other countries. Given this backdrop, the rest of this paper will focus on South Africa, and explore what has been done in the South African literacy context, as well as consider why it has not been that successful in addressing the literacy challenges and what can be done to increase the impact of these interventions.

Despite the education function in South Africa receiving sizable investments of resources (23.4% of the total national budget), the country suffers with significantly poor educational outcomes (Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019; Black & Steenekamp, 2015; Boateng, 2014; IMF, 2020). According to Boateng (2014), it was thought that poor educational outcomes are linked to underspending by governments but as can be seen from South Africa’s case, the high investment in education does not translate into improved outcomes and should not be seen as a solution for the poor quality of education in the country (Boateng, 2014; Mlachila & Moeletsi, 2019).

As highlighted in Table 1, in 2016, 78% of South Africa’s Grade 4 learners were reading below the minimum proficiency level. South Africa’s poor performance in literacy in international and regional benchmark tests has been cause for concern for over a decade. In PIRLS 2006 learners from South Africa achieved the lowest scores of the 40 countries, with about 80% failing to reach the low international benchmark, compared with only six percent of children internationally who did not reach this benchmark (Howie, van Staden, Tshele, Dowse, & Zimmerman, 2012). PIRLS 2011 not only showed how South African learners have low proficiency levels but also highlighted the social achievement gap in this test. In PIRLS 2011 South African Grade 4 learners, particularly those tested in African languages, achieved well below the international centre point even though they had written an easier assessment compared to their counterparts internationally. Learners who were tested in Afrikaans and English performed relatively well and above the international centre point. This is a significant finding as learners who write the test in English and Afrikaans are most likely to be at better resourced schools while those who write in African languages are most likely to be at resource challenged schools where learners do not pay fees. A perpetuation of results like PIRLS 2011 will only reproduce inequality and lock some groups of learners in a vicious cycle of poverty (Moses, van der Berg & Rich, 2017).

The results of PILRS 2016 showed that only 22% of Grade 5 and 13% of Grade 4 learners in the country could achieve the “low international benchmark”, which indicated the ability to identify basic information in a text and retrieve this from the text exactly as it was (Howie et al, 2017). South African learners performed the worst in a pre-PIRLS study in 2011 that included Grade 4 learners of three countries (Van Staden, Bosker & Bergbauer, 2016).

Regionally, South Africa’s performance in the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (SACMEQ) in 2000 and 2007 (SACMEQ II and III respectively) showed that in 2000, almost 66% of South African learners in Grade 6 were not competent in reading at levels 1 to 48, and in 2007, almost 63% of Grade 6 learners were not competent in the same levels although the percentage of learners who were competent at interpretive and inferential reading had improved in 2007 compared to 2000 (Moloi & Chetty, 2011).

Interventions to address the literacy challenge have been driven at national government and provincial government.

The Department of Basic Education (DBE) has promulgated policies and provided strategic direction through national strategies that have been translated to provincial strategies. In recognition of the globally-acknowledged importance of home language in schooling, for promoting inclusivity and for providing children with a strong foundation for literacy and later successful learning (UNESCO, 2008) to prevent and reduce dropout (Ball, 2014) and for promoting multilingualism and developing better thinking skills (Bialystok, 2001; Cummins, 2000), the National Education Policy Act (1996), the South African Schools Act (1996), Language in Education Policy Act (1997), Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (2010) and the Incremental Implementation of African Languages (“IIAL”) policy (2013) all make provision for home language teaching and learning where this is practical to improve the reading abilities of children. However, despite this broad supportive policy landscape, the ideal of home language instruction to improve literacy has not been realised, partly because of resistance by parents in preference to English which they perceive as the language of commerce (Rudwick, 2008; de Klerk, 2000) and partly because of the mismatch between teacher and learner home languages (WCED, 2017). However, whether reading is taught in English or home language, if it is not taught effectively, children’s future learning will be jeopardised.

The DBE also developed a National Reading Strategy in 2008, aimed at increasing access to books and providing support to teachers through resources and techniques to promote a love of reading so as to improve learners’ reading competencies. Interventions supporting the strategy include the piloting of the Early Grade Reading Study (EGRS) in 230 schools (50 intervention schools each for each intervention model and 80 control schools) in the North West (NW) (DBE, 2019a; DBE, 2019b) and 180 schools in Mpumalanga provinces where cohorts of Grade 1 learners in NW received the intervention for three years from 2015 (EGRSI), and those in Mpumalanga received it over two years in 2017 and 2018 (EGRSII). In both cohorts, outcomes and other data were collected from learners in the interventions and control groups. In the NW province, the EGRSI had three interventions over three years, each with 50 schools:

The EGRSI in the NW supported teachers in the teaching of Setswana as a Home language while EGRSII in Mpumalanga supported the teaching of English as a First Additional language (DBE, 2020). Drawing on lessons from EGRSI, EGRSII which also provided scripted lesson plans and reading resources as well as coaching and training utilised two different strategies to training and coaching:

More recently, the Read to Lead Campaign (2015 – 2019) was concretised with the formation of a National Reading Coalition, which was launched in February 2019 to improve the coordination of various reading interventions among stakeholders “to reduce inefficient overlaps and gaps” (National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) website, 2019). The coalition will focus on multiple areas for the holistic development of reading — “initial teacher preparation; access to relevant resources; continuing professional development; community support; policy, research and evaluation” (NECT website). In fulfilling its role as a coordinating body for maximising collaboration among stakeholders to reduce duplication and overlaps, the NECT, in collaboration with DBE and the Education Training and Development Practices (ETDP) Sector Education Training Authority (SETA), is involved in the implementation of the Primary School Reading Improvement Programme (PSRIP) implemented in 2016 and 2017, focusing on teacher training, resource provision and classroom support across all nine provinces in 1,670 schools in 51 districts (NECT, 2017).

The National Reading Strategy resulted in provincial strategies including the Gauteng Primary Literacy Strategy, 2010-2014, Western Cape Education Literacy and Numeracy Strategy (2006 – 2016) and Western Cape Reading Strategy 2020 – 2025, all aimed at improving reading in the provinces. These strategies have been accompanied by implementation of interventions by various organisations, some of which are mapped in Table 2, which presents only a selective number of interventions that have achieved relative success in improving learning outcomes.

Table 2: Early Grade Literacy Providers and their Interventions

Name of Organisation |

Description |

Province(s) |

Evidence |

Funda Wande Started in 2015 |

Not-for-profit organisation that aims to ensure that all learners in South Africa can read for meaning in their home language by the age of 10 through video and print materials and teacher training on effective techniques to teach reading. The intervention is being implemented in three districts in the Eastern Cape with 10 schools per district. |

Eastern Cape

|

SALDRU at the University of Cape Town is conducting an RCT external impact evaluation. |

Class Act |

Develops materials in both African languages and English First Additional Language (EFAL) in the Foundation Phase, primarily focusing on lesson plans and rollout of programmes such as EGRS for DBE and PSRIP for NECT. |

Countrywide |

The PSRIP has been evaluated and found to have positive effects. |

READ Educational |

A teacher development agency in language, literacy and communication and is a leader in educational assessment, materials development and resource provision. READ has experience in both rural and urban school-project delivery. READ is currently implementing the Roger Federer Foundation School Readiness Initiative together with other service providers. |

National |

READ’s programmes have been evaluated in Zambia and found to be effective. |

| Room to Read (RtR) Started in SA in 2006 |

Works in collaboration with local communities, partner organizations and governments to offer a comprehensive Literacy Program that combines home-language classroom instruction with high-functioning libraries and teacher training. DBE appointed Room to Read as an implementing partner for its Read to Lead campaign, aimed at establishing or refurbishing 1,000 school libraries annually. |

Eastern Cape Limpopo Mpumalanga Gauteng Worked in a total of 469 schools, 1,021 teachers and 362,180 students |

By the end of grade 2, children in Room to Read's Literacy Program read two to three times as fast and read with 87% greater comprehension than their peers in non-Room to Read program schools. |

Wordworks Started in 2005 |

Focuses on early language and literacy development in the first eight years of children’s lives. Focuses on parents and caregivers, family and community members, early childhood development practitioners and Grade R to Grade 3 teachers. Partnered with the WCED from 2015 – 2018 to roll out a maths and literacy programme for Subject Advisors and Grade R-teachers which included provision of materials and a three-level cascade model that commences with the training of subject advisors, uses Lead Teachers as intermediate trainers, and ends with teacher training. |

Eastern Cape Gauteng KwaZulu-Natal Western Cape |

An external evaluation concluded that the interventions had an initial positive effect on the language and literacy achievement of targeted learners. However, the initial gains in the first half of Grade R diminished by the end of Grade R and had been lost by the end of Grade 1. |

| Save the Children | The School Capacity Innovation Project (SCIP) was initially piloted in rural districts in Mpumalanga and FS. In 2016 the project was extended for a three-year period to work in all five districts in the FS. The overall goal is to support the Free State Department of Education to rapidly achieve improved learning outcomes in African Home Language (AHL), as well as EFAL for all learners in Grades 1 to 3. | Free State Sepedi |

Pre- and post-tests with teachers in the project showed improvements in knowledge and skills. Learner outcomes, measured using the EGRA assessments administered to intervention and control schools, showed appreciable improvements in the intervention group compared to the control group. |

| Molteno Institute for Language and Learning Started in 1974 |

Developing literacy through teaching and learning materials, as well as providing institutional training and classroom mentoring to developing communities in Africa. Developed the first set of graded reading materials in all 11 official South African languages, being utilised by four provinces in the country. | Gauteng, Eastern Cape, Limpopo, Free State |

The impact of the use of these materials have been documented by independent evaluators. More than 20 external evaluations have been commissioned by Foreign Aid Agencies like USAID, DFID, UNESCO and the HSRC – all of them positive. |

Source: JET Education Services, DNA Economics & Bertha Centre, 2020

Despite multiple interventions over the years to improve early grade literacy, persistent challenges exist as partly evidenced by the PIRLS results. Several complex factors can be attributed to the relatively limited success, in turning the system to improve early grade literacy, of the interventions that have been implemented so far. A few key factors are discussed in turn as a precursor to the value proposition of OBC.

According to the DBE, in 2016, South Africa had 25,574 ordinary schools enrolling 12,932,565 learners (DBE, 2018). For any universal impact to be achieved, interventions would have to be focused on all the schools or at least all quintiles 1-3 schools9 serving 77% of the learners through the government’s no-fee policy (UNICEF, 2018). As we have seen in the description of the EGRS and some of the interventions in Table 2, the interventions are scratching the surface in terms of reach, with the widest reach of the discussed interventions having been 1,670 schools across all nine provinces through the PSRIP, followed by 469 schools in four provinces by the RtR intervention. The two EGRS pilots that were implemented in two provinces reached less than 200 schools and they have not been scaled despite showing positive effects on literacy and learning.

Most interventions do not include evaluation of impact. A meta-evaluation by Besharati and Tsotsotso (2015) which utilised a standardised and comparative framework to evaluate the results of impact evaluations of interventions to improve learning outcomes in South African public schools in the democratic dispensation, identified 28 evaluations of 30 varied interventions aimed at teachers and learners, management and whole school development. From these 28 evaluations, only six, five implemented by private providers (the Reading Catch-Up programme (RCUP); two READ Primary School programmes in the Eastern Cape, the Learning for Living project (LfL), another READ intervention; and the Mother Tongue Literacy Programme) and one initiated by government, Gauteng Provincial Literacy and Mathematics Strategy (GPLMS) program were considered to be rigorously evaluated.

In their analysis, Besharati and Tsotsotso concluded that the majority of education interventions in South Africa had very small effect sizes and some had negative learning outcomes, and there was no indication that simple, less costly interventions, like provision of quality teaching and learning resources, were less effective than more complex and more expensive interventions like whole school evaluation. Importantly, the meta-evaluation found that interventions implemented in the early grades had greater learning impact than those implemented in the higher grades.

The EGRS, which came after Besharati and Tsotsotso’s meta evaluation was evaluated for impact using Randomised Control Trial (RCT). The evaluation of EGRS1 found that the coaching intervention, which was about 40% more expensive than the centralised training model (R557 per learner per year compared to R397), was about twice as effective on learner reading. In the intervention groups where lesson plans and reading materials were augmented with coaching, between 10% and 20% more children surpassed specific reading fluency benchmarks at the end of Grade 2 compared to children in control groups. Home language reading and English achievement also improved, and it also helped boys catch up to girls. The EGRSI evaluation also concluded that learners in intervention schools were 40% of a year of learning ahead of the learners in the schools that did not receive the intervention (Taylor, Cilliers, Prinsloo, Fleisch & Reddy, 2018). Following the positive results of EGRSI, various projects providing lesson plans, coaching and reading materials have been initiated in different provinces, including the Funda Wande project10 (Funda Wande, 2019), (Ardington & Meiring, 2019), and a Sesotho version intended for Limpopo. However, as indicated earlier, the scale of the initiatives is very small compared to the need.

A major constraint to rolling out the interventions to a majority of the schools and learners that would benefit from them is cost. EGRSI, which has produced positive results, has not been rolled out to scale in the North West province or to other provinces. If the EGRS is to be implemented in all quintile 1 – 3 schools, this would mean a roll out in ~12,347 schools11 (DBE, 2019b). The cost of implementing EGRSI over three years was ~R15 million, all of which came from donors — UNICEF, Anglo-American, ZENEX. The impact evaluation costs of ~R6 million came from 3ie. EGRSII, which has entirely been funded by the USAID cost about R35 million over three years for implementation in 100 schools.12 The cost of implementing the EGRS in Grades 1-3 currently for 50% (7,500) of South African schools would be ~R1.3 billion a year (Spaull, 2019b).

It is not impossible to raise this funding internally from DBE as well as corporate social investment (CSI). CSI to the education sector has been on an upward trend and in 2019 amounted to about R5.1 billion, constituting 50% of the R10.2 billion CSI funding that year (Trialogue, 2019). However, the CSI funding is dispersed directly to many discreet interventions and not to large-scale impactful interventions. There are also multiple discrete early-grade literacy interventions being funded by private company and corporate foundations like the Zenex Foundation, grant managers like Tshikululu Social Investments, and charitable trusts like the DG Murray Trust and ApexHI Charitable Trust. If all the discrete interventions redirected their efforts and funding to an intervention like EGRS that has shown positive outcomes literacy outcomes could improve.

Another implication of lack of funding is the limited length of interventions — change takes time and EGRSI was implemented over three years and EGRSII over two years as they were financially well-backed. Some projects with limited financial backing may not last that long. Sustainability of learning effects is also important and has to be factored into the design of interventions, which will also cost money to continue supporting interventions and measuring effects over time.

OBC, the design of the intervention would address all risks to the achievement of outcomes.

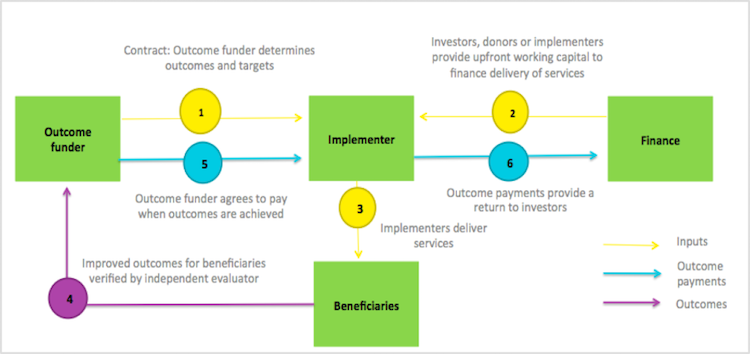

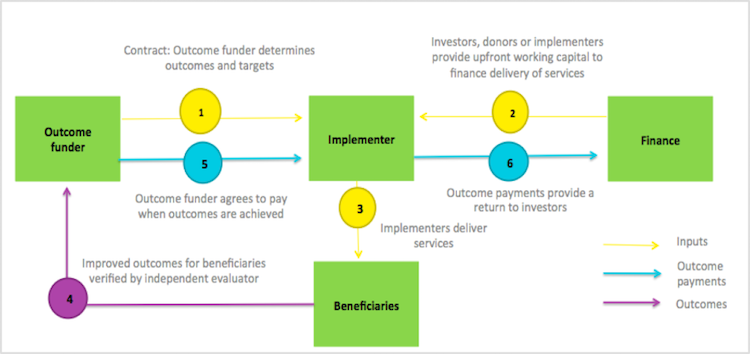

Outcomes based contracting, an instrument of the results-based financing (RBF) mechanism, is “a program financing arrangement in which payments are contingent upon the achievement of predefined results (outcomes), which are usually verified by an independent evaluator” (Bertha Centre, n.d.). There are different types of OBCs based on the proportion of payment dependent on agreed results. Performance linked payment that constitutes a small proportion of the contract could be adequately funded by donors but larger ones may require socially motivated investors who can provide risk finance (development impact bond — DIB). If government pays for all or some of the performance payment it is referred to as a social impact bond (SIB). Figure 1 provides a process flow of an OBC.

Figure 1 : Process flow of outcomes-based contract

Source: Bertha Centre, OBC primer

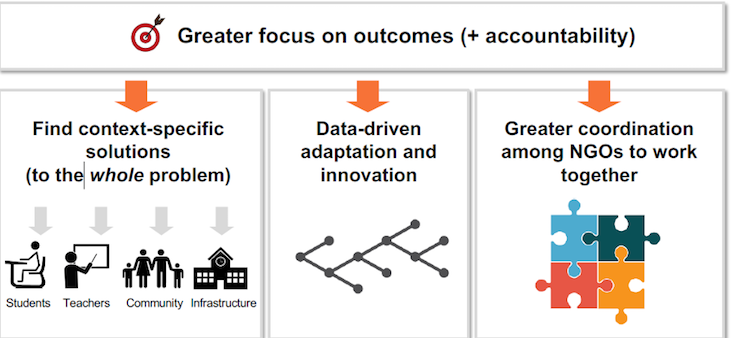

The underlying theory of change for OBC is that the offer of a financial incentive to an implementer (service provider) for meeting agreed outcomes motivates better monitoring for learning and use of data to innovate and adapt implementation for better results. If applied to literacy interventions, the incentive for achieving or surpassing outcomes will most likely lead to a holistic approach to improving literacy outcomes that will result in system strengthening and more sustainable results. This would entail tailoring implementation to specific contexts and not adopting a one size fits all approach. In this regard, multiple NGOs offering different solutions may need to pool together to provide a comprehensive solution to a single problem. Figure 2 provides an overview of the key OBC elements.

Figure 2 : Key components of OBC

Source:EOF Fundraising prospectus, 2019

Drawing on the main challenges that could be leading to low literacy outcomes in South Africa and the inability to scale the EGRS, Table 3 juxtaposes the challenges against an OBC value proposition.

Table 3: How OBC can Address Poor Literacy Challenges

Challenge |

How OBC Could Address this Challenge |

There are too many discrete interventions at small scale which result in a thin spread of donor funding. |

Better funding: Only interventions that work like EGRS and those with potential to improve outcomes like PSRIP will be funded. Bids from multiple providers will enable government to understand the cost per outcome of various interventions leading to contracting of best value interventions. In other countries OBC would also promote funding of projects were there is evidence of impact. |

EGRS I and II funding came from donors and there is lack of funding to implement EGRS to scale. |

More funding: Advocating for funding only interventions that work has the potential to attract more funding from donors. More funding is required as COVID-19 will contract education budgets |

NGOs are implementing discreet interventions that are hyper localised and are not evaluated. |

Better alignment: There is potential to attract more funding from CSI towards systemic interventions that have been proven to work. More CSI funding can be channelled to DBE and NECT to fund impactful interventions. NGOs can be mobilised to collaborate and deliver services that complement each other towards improvement of learning outcomes. |

Service providers who implement interventions are not accountable for results |

Knowledge and data: Rigorous evaluation will improve transparency, accountability and improve an outcomes orientation. |

South Africa is planning to pilot an OBC EGRS in KwaZulu Natal starting in 2020, which will provide valuable lessons for the efficacy of OBC and the extent to which incentivizing service providers results in better outcomes (DNA Economics, 2020).

The challenges highlighted in Table 3 may not be exclusive to South Africa, and the degree to which OBC can address issues of limited funding and solve inefficiencies could work in other countries that want to increase the effectiveness of literacy programmes to ensure that learning improves and their education systems are prepared to prevent learning loss, should emergencies similar to COVID-19 happen again. Learners who can read limit learning losses as they can continue learning at home if they have access to learning resources and the space to learn at home. The ability to read will result in more sustainable education systems where learners can learn from anywhere and persist in school because they can decode their school work in all subjects better.

Development of literacy in the early grades is foundational for all learning in school, and with 53% of Grade 4 learners in low- and middle-income countries who cannot read for meaning, education systems in these countries will remain inefficient. Our analysis of per learner investment in primary school suggests that most countries, even those with lower levels of Grade 4 learners below the minimum proficiency level, seem inefficient. Using South Africa as an example, we have suggested that the causes of low literacy skills among learners could be caused by the implementation of many small and uncoordinated interventions which do not have any evidence of impact, short implementation timeframes, funding constraints to implement to scale, and input based contracting models which do not hold service providers accountable for outcomes of interventions. To improve efficiency of education systems in resource challenged low- and middle-income countries, consideration should be given to the use of outcomes-based contracting to scale interventions that work and improve their likelihood of success by paying service providers for the number of children who are able to read at agreed proficiency levels at certain points in the intervention. This will ensure that governments, if they are paying for some outcomes, investors and funders, and service providers all carry equal risk and work diligently and creatively to achieve agreed-upon results. Carrying on with the way early grade literacy interventions have been implemented in the past defeats the objectives of creating sustainable education systems and reducing socio-economic inequalities through education. South Africa’s piloting of an EGRS pilot will provide important lessons on the feasibility of this approach.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to colleagues whose guidance and inputs through discussions and review of our other work has shaped our development in the area of innovative finance and have contributed to this paper. We are particularly grateful to Dr Susan de Witt of the Bertha Centre for planting the seed and nurturing our interest in innovative financing mechanisms in education, particularly outcomes-based education. We would also like to acknowledge Dr James Keevey for encouraging us to write this paper, Dr Nick Taylor, and Fouche Venter of DNA Economics, for discussions and ideas in other work on OBC. Contributions by Jarred Lee and Alina Lipcan of the Education Outcomes Fund in the EOF South Africa scoping study also influenced our work. We take full responsibility for the ideas expressed in this paper.

Notes

Ardington, C., & Meiring, T. (2019). Update on the impact evaluation of the Funda Wande Eastern Cape Pilot. https://fundawande.org/news/update-on-the-impact-evaluation-of-the-funda-wande-eastern-cape-pilot--cally-ardington--tiaan-meiring-7

Ball, J. (2014). Children learn better in their mother tongue: Advancing research on mother tongue-based multilingual education. Global partnership for education. https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/children-learn-better-their-mother-tongue

Bertha Centre. (n.d.). Contracting for results: OBC primer. Bertha Centre

Besharati N. A., & Tsotsotso, K. (2015). In search for the education panacea: A systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of interventions to improve learner achievement in South Africa. University of the Witwatersrand.

Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy and cognition. Cambridge University Press.

Black, P. A., Calitz, E., & Steenekamp, T. J. (2015). Public economics (6th ed.). Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

Boateng, N. A. (2014). Technical efficiency and primary education in South Africa: Evidence from sub-national level analyses. South African Journal of Education, 34(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071117

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire (Bilingual education and bilingualism, 23). Multilingual Matters.

Cunha, F., Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L. J., & Masterov, D. V. (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In E. A. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.). Handbook of the economics of education. Elsevier. 697-812.

DBE. (2018). Education statistics in South Africa 2016. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Basic Education.

DBE. (2019a). The Early Grade Reading Study: Results of Year 2 Impact Evaluation. Summary Report. Department of Basic Education. https://www.education.gov.za/Programmes/EarlyGradeReadingStudy.aspx

DBE. (2019b). The Early Grade Reading Study Sustainability Evaluation: Technical Report. Department of Basic Education. https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/EGRS/EGRS%20I%20Wave%204%20Report%202019.pdf?ver=2019-05-31-111638-587

DBE. (2020). The Second Early Grade Reading Study: Early perspectives – The situation at the start of Grade 1. Pretoria, South Africa: DBE.

de Klerk, V. (2000). To be Xhosa or not to be Xhosa … That is the Question. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21(3), 198-215. 10.1080/01434630008666401

DNA Economics. (2020). Outcomes based contract for an early grade literacy intervention: Feasibility and design report. Pretoria, South Africa: DNA Economics.

EOF. (2019). A game changing way to finance results in education: Fundraising prospectus. London: EOF.

Funda Wande. (2019). Limpopo Proposal. Unpublished mimeo.

Heckman, J. J., & Masterov, D. V. (2007). The productivity argument for investing in young children. Review of Agricultural Economics, 29(3), 446-493.

Howie, S. J., Combrinck, C., Roux, K., Tshele, M., Mokoena, G. M., & McLeod Palane, N. (2017). PIRLS Literacy 2016 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study 2016: South African children’s reading literacy achievement. Centre for Evaluation and Assessment.

International Monetary Fund. (2020). IMF Country Report No. 20/33: South Africa. International Monetary Fund.

Jansen, J., & Amsterdam, C. (2006). The status of education finance research in South Africa. Perspectives in Education, 24, 11.

JET Education Services, DNA Economics & Bertha Centre. (2020). Education Outcomes Fund South Africa Scoping Study: Scoping Report. JET.

Mlachila, M., & Moeletsi, T. (2019). Struggling to make the grade: A review of the causes and consequences of the weak outcomes of South Africa’s education system. IMF Working Papers, 19(47), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781498301374.001

Moloi, M. Q., & Chetty, M. (2011). Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality: Trends in achievement levels of Grade 6 pupils in South Africa. Policy Brief: SACMEQ.

Moses, E., van der Berg, S., & Rich, K. (2017). A society divided: How unequal education quality limits social mobility in South Africa — Synthesis report for the Programme to Support Pro-Poor Policy Development (PSPPD). Research on Socio-economic Policy. Stellenbosch, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch.

National Education Collaboration Trust. (2017). Primary School Reading Improvement Programme booklet. NECT.

National Education Collaboration Trust. (2019). What is the National Reading Coalition? https://nect.org.za/in-the-media/nect-news/what-is-the-national-reading-coalition

Rudwick, S. (2008). “Coconuts” and “oreos”: English-speaking Zulu people in a South African township. World Englishes, 27(1), 101-116.

Spaull, N. (2019a). Learning to read and write for meaning and pleasure. In N. Spaull & J. Comings (Eds.), Improving early literacy outcomes. Brill Sense Publishers.

Spaull, N. (2019b). Equity: A price too high to pay? In N. Spaull & J. Jansen (Eds.), South African schooling: The enigma of inequality. Springer.

Spaull, N., & Pretorius, E. (2019). Still falling at the first hurdle: Examining early grade reading in South Africa. In N. Spaull & J. Jansen (Eds.), South African schooling: The enigma of inequality. Springer, Cham.

Spaull, N., van der Berg, S., Wills, G., Gustafsson, M., & Kotzé, J. (2016).Laying firm foundations: Getting reading right — Final report to the Zenex Foundation on poor student performance in foundation phase literacy and numeracy. http://resep.sun.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/ZENEX_LFF-email.pdf

Taylor, S., Cilliers, J., Prinsloo, C. Fleisch, B., & Reddy, V. (2018). The Early Grade Reading Study: Impact evaluation after two years of interventions. Technical Report. Unpublished.

Trialogue. (2019). Business in Society Handbook 2019. Trialogue.

UNESCO. (2008). Mother tongue matters: Local language as a key to effective learning. UNESCO.

UNICEF. (2018). Education Brief Budget South Africa 2018/19. UNICEF.

van Staden, S., Bosker, R., & Bergbauer, A. (2016). Differences in achievement between home language and language of learning in South Africa: Evidence from pre-PIRLS 2011. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 6(1), Article 441.

WCED. (2017). Curriculum GET minute: DCG 0012/2017. https://wcedonline.westerncape.gov.za/circulars/minutes17/CMminutes/edcg12_17.html

World Bank. (2019a). Global partnership for education finance. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/656401571859221743/FINAL-EDU-Finance-Platform-Booklet.pdf

World Bank. (2019b). Learning poverty. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/brief/learning-povertyAuthors:

Monica Mawoyo is a research associate at JET Education Services. She has a PhD in Education from the University of Cape Town and has been an independent researcher for the last 21 years. Monica’s research interests are initial teacher training, ICTs in education, student access and success, student funding, early grade literacy and numeracy, innovative financing in education and skills development. Email: monica@jet.org.za

Zaahedah Vally is a researcher at JET Education Services, working across research and implementation projects. She received her Bachelor's degree in International Relations with the University of South Africa (UNISA) and a Postgraduate Diploma in Management (Monitoring and Evaluation). Currently completing her Master's degree in Management (Development and Economics), Zaahedah is passionate about driving socio-economic change in South Africa by improving the quality of education in the country. Email: zaahedah@jet.org.za

Cite this paper as: Mawoyo, M., & Vally, Z. (2020). Improving education outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: outcomes-based contracting and early grade literacy. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(3), 334-348.