2020 VOL. 7, No. 3

Abstract: In March 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic obliged Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in many countries to vacate their campuses and operate at a distance. We narrate the experience of the Acsenda School of Management (ASM) in making this sudden transition. ASM is a private for-profit business school with some 1,200, mostly international, students based in Vancouver, Canada. Drawing on interviews with ASM staff the paper identifies why the transition was relatively successful. It concludes with reflections on the longer-term impact of COVID-19 and how to integrate online and distance learning more effectively in HEIs around the world.

Keywords: COVID-19, HEI, online and distance learning.

In the early months of 2020, the COVID-19 disease, caused by a novel coronavirus, spread rapidly around the world, causing thousands of deaths and severe economic disruption. Most countries ordered the closure of their schools and colleges to slow the spread of the infection (Daniel, 2020). By the end of March, 1.37 billion students — nearly 80% of the world student population — were at home, with governments and institutions scrambling to “scale up multimedia approaches to ensure learning continuity” (UNESCO, 2020).

The Acsenda School of Management (ASM) in Vancouver, Canada, shut down its campus and moved its activities online in March. As the institution’s Chancellor (a figurehead role), I had the opportunity to observe its adaptation to this sudden upheaval without being personally involved in any of the many changes involved. My background is a 30-year career in higher education administration, notably in open and distance learning institutions, followed by ten years at senior levels in international intergovernmental organisations.

By late April I concluded that ASM had handled the move off campus competently and, with the agreement of the president, I decided to try to capture the elements of its approach. Over a two-week period, I interviewed 12 ASM staff members by phone and attended a drop-in meeting of faculty over Zoom. I am grateful to these colleagues for talking to me and quotations from them are identified in the text. In mid-May I circulated a draft of this narrative to those I had interviewed, but I take full responsibility for any errors of fact or interpretation.

The Acsenda School of Management is a private, for-profit business school in Vancouver, British Columbia (BC). In 2004 the Sprott-Shaw Community College (founded 1903) created the Sprott-Shaw Degree College. It received consent from the BC government to offer a Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) degree and enrolled students in 2005. In 2008 the Degree College was acquired by the CIBT Group before becoming part of the EduCo International Group, an Australian company. Meanwhile the college had gained approval to offer a direct-entry four-year Bachelor of Hospitality Management (BHM) degree and changed its name to the Acsenda School of Management.

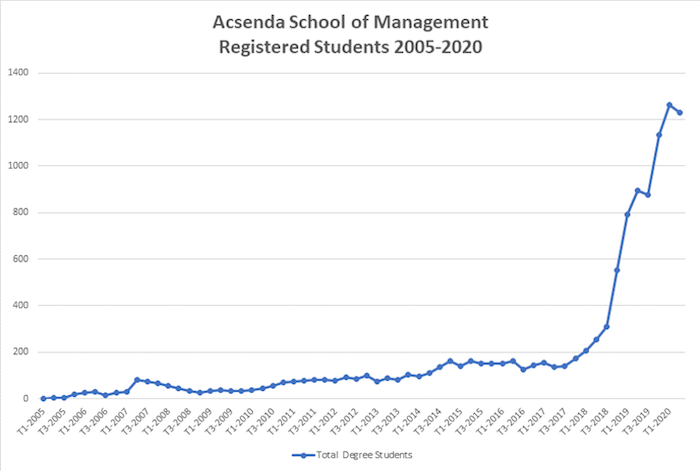

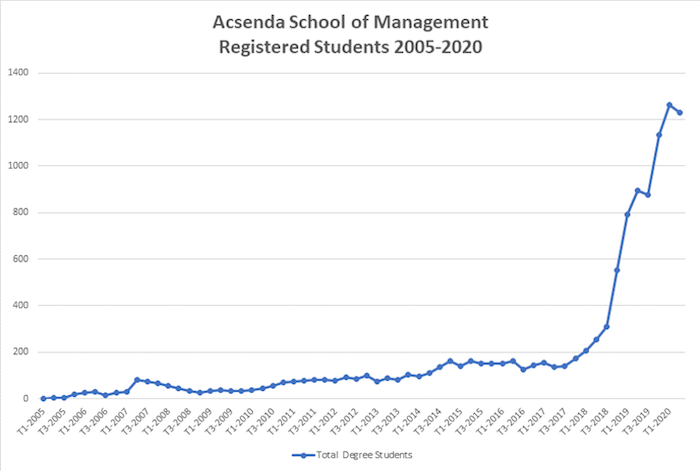

From its establishment in 2004, until its acquisition by the EduCo International Group in 2016, ASM struggled to enrol more than 200 students annually. Under EduCo student recruitment increased sharply, necessitating moving to a larger campus. In the 2020 year, ASM enrolled over 1,200 students, as illustrated in Figure 1, the large majority from some 40 countries outside Canada.

Figure 1: ACSENDA registrations

All ASM’s teaching occurred in the classrooms on its Burrard Campus until the COVID-19 pandemic struck early in 2020. Already in 2019, ASM’s Strategic Planning Committee had begun discussions about incorporating more blended learning into the curriculum, moves that were primarily motivated by considerations of pedagogy, lifelong learning and preparing students to use technology in the workplace. A local transit strike, campus closures due to extreme weather and the search for timetabling efficiencies were other incentives for integrating more technology into the curriculum. These discussions led to a three-year plan that proved helpful when ASM had to vacate the campus quickly, even though it was not aimed at transforming ASM into an online HEI.

Although world leaders were slow to react to COVID-19 and appreciate its infectiousness and lethality, British Columbia acted more quickly than most jurisdictions. This was partly because in the US the first case (January 21) and the first death (February 26) occurred in neighbouring Washington State. BC has a well-integrated health-care system that includes long-term care homes. When its first outbreak occurred in one of these care homes on March 6, the alarm was raised immediately.

The BC government had issued an advisory on January 27 and, although the risk was then considered “low”, ASM’s president and the EduCo officer responsible for Canada initiated discussions within EduCo and sought information from the BC Council for International Education on actions proposed in BC. On February 13, following a request from ASM’s Occupational Health & Safety Committee, cleaning practices on campus were intensified with full sanitisation, cleaning three times a day and the placement of wipes and hand-sanitisers around the campus. ASM was assured that the campus air filtration system was similar to those in hospitals.

On March 5, ASM held a first COVID-19 meeting to explore putting the term’s final exams online — but still in the expectation that ASM would be back on campus by March 30.

Discussions had been underway between EduCo, ASM, Arbutus College and other parts of the EduCo network about COVID-19. Corporate-level business travel was restricted and the senior leadership team initiated a scenario-planning process and the development of a campus response plan. Staff and faculty were reminded to disclose all business and personal travel.

On March 6, a message to ASM students, faculty, staff and Academic Council indicated where to find more information about COVID-19 and alerted the campus community that changes might be forthcoming. A public awareness campaign on campus provided information about the virus and the precautionary measures that people could take. ASM established an AskAboutCovid helpline, an online chat feature about health and safety and began development of a COVID-19 webpage with information for current and future students, faculty, staff and other stakeholders.

On March 7, University Canada West (UCW), another local for-profit institution, had a case of COVID-19 and shut down for three days. ASM and UCW share some student accommodation, so ASM realised it had to take the situation very seriously and ramped up its preparations, with scenario planning for a full or partial shutdown. Some ASM faculty teach at other HEIs and were able to gather intelligence about the gathering storm.

Starting on March 7, acting on his belief that communication channels are most important in a crisis, the president communicated regularly with the Academic Council and the students. Checks were made on students coming from affected countries and discussions with EduCo intensified. Classes continued on campus in the week of March 9 but ceased for the week of March 16, with the campus finally closing on April 3.

March 7 heralded a period of intense preparation, under the guidance of the vice-president, academic (VPA), for moving all academic activities off campus. Preparations were made to implement the technology framework for a shift to online learning and a virtual classroom software: Big Blue Button, was added to the Moodle learning management system. The original intention had been to introduce this in October 2020.

An important executive meeting was held on March 10. Final exams would be online, and no one would come on campus in finals week; faculty should set take-home exams where they counted for more than 20% of the marks and give additional assignments where they counted for less than 20%. Implementation of these decisions was “a bit bumpy but 95% successful” (interviewee quotation).

ASM began preparations of a student support strategy and the development of systems and information to help students. A two-week quarantine period was being introduced for persons entering Canada, which raised concerns about student adjustment, feelings of isolation and access to essential needs.

By March 16, ASM realised that it could not soon return to campus. To operate online, it explored the use of Zoom and integrated the BigBlueButton (BBB) open source web conferencing system with ASM’s existing Moodle system. Moodle was already integrated with the Student Information System.

On March 17, the leadership team decided to move all teaching online for the coming term. BBB would be the main platform with Zoom as a backup, although Zoom could have worked as the main platform, too, and, according to later surveys, was preferred by faculty and students.

On March 19, a Zoom meeting was held for all ASM faculty and some from Arbutus College (another EduCo affiliate). The VPA said this “was a good session with lots of energy and supportive participants. The tools were in place and the faculty enthusiastic”. From this point the VPA felt that ASM was in good shape for the transition.

March 23 saw orientation of the new student intake using a fully virtual system, including a new online payment system.

In the period March 22-27, two IT-skilled staff members were identified as BBB and Moodle coaches. They contacted all faculty and supported them through the week March 22-27, doing an “amazing job” (interviewee quotation) in getting everyone online, despite steep learning curves. Only a few faculty members had major difficulties. A stipend of $75 was paid to faculty for attending the first of a series of weekly training sessions on the use of Zoom. There were also weekly drop-in meetings, hosted by the VPA, to share practice. Having attended one such meeting on May 7, I can attest that they were popular and successful, pooling the remarkable collective knowledge of the faculty about technology-based teaching and learning systems.

By March 30, everyone was ready, and, despite some outages, there was a successful test run. The tricky issues were server capacity, sharing webcams and creating videos. ASM was identified by Zoom as a special organisation (lifting the 40-minute meeting limit) and all ASM staff and faculty were asked to sign up with Zoom individually as a backup. In the first week of classes ASM struggled a bit and 20% of courses encountered difficulties but by the end of the week problems with the server had been identified and dealt with through real-life testing. On April 10 arrangements were made with EduCo to record student presence and participation, which is now done more assiduously than it used to be in the classrooms.

Was any Previous Planning Useful?

Some previous planning, both by ASM as a corporate body and by some of its staff, did prove useful, although it had not been carried out in the expectation that a global pandemic would close down the institution’s normal operations almost overnight. One view was that ASM benefited from not having detailed plans for this particular eventuality. Addressing problems as they arose was a better approach.

After years of complaints at the Academic Council about the ineffectiveness of the student record system, ASM had introduced a new Student Information Management System in 2018. This enabled a wider range of online management of student records, registration, financial, and course/learning management. Both the system and the processes underpinning it had recently been comprehensively reformed to make them simpler. As well as being a virtue in itself, the system’s simplicity makes it easier to transfer registrarial staff between tasks; an important consideration because ASM-trained staff are attractive to other HEIs and turnover in the registry is high. An effective and accurate Student Information System, including records of faculty and staff attendance, proved to be even more important for online operations because only the system ‘knows’ who was present in courses. It is also the basis for the official reports to governments. Training faculty on the new system had gone well, although some 15% still needed additional support with the new technology.

Technology was a greater challenge with students, many of whom have a limited command of English and needed the reassurance of talking to someone. E-mail traffic about administrative questions increased dramatically after operations went online. The registrar also deals with changes of schedule. This term, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, ASM enrolled significantly fewer students than expected, so the schedule had to be adapted and sessions cancelled in an equitable manner.

Also, at the corporate level, the Academic Council had been musing in a desultory way for some years about the implications of e-learning for ASM’s future. The general view was that ASM’s key strength, and the characteristic most valued by students, was the personal contact among students, faculty and staff, implying that online teaching and learning might be helpful at the margins but was not a mainstream concern. Nevertheless, in 2017 the Strategic Planning Committee had been asked to examine the potential of online methods, to assess the pedagogical, organisational and technological opportunities that they might afford, and to make recommendations. This led to the presentation of a Strategic Technology Plan in November 2019.

This plan aimed to achieve the following impacts between 2020 and 2022:

Key outcomes of the plan are to:

This was not a plan for converting ASM into an online teaching institution. Nevertheless, staff felt that the reflections stimulated by its formulation did prove useful as ASM faced the very different challenge of taking the institution 100% online in a few days. Although these previous discussions had assumed considerable use of asynchronous approaches, there simply was no time to prepare such materials, so most of the teaching had to be synchronous: “you do what you were doing in class, but online” (interviewee quotation).

The whole BBA curriculum was revamped in a week. The dean assessed which faculty members were most “online ready” and trained them first. Focus groups of the faculty teaching each course had daily meetings to revise the curriculum. They also reviewed pedagogy and came up with a four-element structure, having decided that three hours was too long for an online lesson:

At first the dean visited each focus group daily to encourage co-operation between faculty. The meetings then moved to a weekly schedule. There was also a weekly meeting outside the focus groups. The VPA also had all faculty members check in weekly.

The dean judged that ASM’s earlier planning discussions about online teaching proved helpful, as did tips from other institutions (e.g., minimising time for open-book exams to give less time for consultation). ASM instituted a dress code for students for online lessons (no pyjamas!) and insisted that students raise their hands frequently to ensure participation.

During exams’ week a new faculty member with strong IT experience did video training and one-on-one sessions with faculty in the use of Moodle. This was an example of relatively new staff members blossoming in this crisis.

The technology plan, developed over the previous three years for a different purpose, had to be re-versioned for implementation in two weeks. Some key technology updating (e.g., the plagiarism checker) had already been done, but other projects hanging fire (e.g., an online payments system and putting fillable forms online) were now carried out. This was done alongside the upgrade on March 29 of an old version of Moodle that had been planned for October, which included integrating and configuring, on the fly, the open source web-conferencing system BigBlueButton, also used by the University of British Columbia (UBC). This all had to be done at a time when IT service providers were experiencing huge increases in systems usage, leading to many outages. Zoom was offline for hours. The upgrade did not work perfectly because “we didn’t understand enough about the system” (interviewee quotation) but registration took place over the phone and on BBB.

Faculty quickly developed successful approaches to using Zoom; such as the importance of starting sessions with short icebreakers to “warm people up and get better engagement among the students” (interviewee quotation). The BBA has classes of around 25-35 students and its thirty faculty represent twenty-five nationalities. These sessions helped participants to appreciate ASM’s diversity.

E-learning works best when pre-prepared material, used by students asynchronously, is blended with synchronous class discussions in break-out rooms on Zoom. Although few faculty had asynchronous materials ready in advance, this blend worked well for those that did, and a later survey showed that students would like to have more asynchronous teaching. Using ‘scramble’ for allocating students to the break-out rooms, and asking students to leave their cameras turned on, broke down barriers and led to some good discussions.

Among the faculty, previous experience of online teaching and learning varied widely. One, who had been an early adopter of Moodle and other distance learning tools, was already moving courses online and helped colleagues to put their exams online. The few who had already developed distance learning materials for asynchronous use found that know-how helpful. From their experience of teaching at other BC institutions some faculty were familiar with a variety of online tools (BigBlueButton, BlueJeans, Collaborate, Zoom, Moodle). As already noted, the readiness of faculty to share experience and know-how with each other was impressive.

In the vital area of English for Academic Purposes, exploration of online teaching and learning had been going on at ASM for over a year. The VPA circulated an important document about the privacy restrictions on recording students’ use of Zoom.

After the decision to close it, the campus had to be shut down in a systematic way. Fortunately, the staff member responsible had previous experience of closing down operations in another organisation and could do this in an orderly and recorded manner.

This work involved:

From March 7, the president communicated regularly with staff, students and the Academic Council. The staff member responsible for communications keeps students informed and projects the persona of ASM. Prior to COVID-19, this work focussed on text exchanges because students could interact with each other and staff by coming to campus. The task now is to “get the word out and push content at them” (interviewee quotation), especially video content and infographics. He taught himself video production and graphic design and aimed to ensure a ‘cornucopia of student interaction’ (interviewee quotation) with more engaging content. The situation is in constant evolution, with something new every day. He relies on data and analytics to assess the impact of his work: e.g., attendance at group sessions; how many people open emails; weekly reports on social media. An EduCo affiliate also provides some useful material and the president hosts a live video meeting with students every week and posts a video update.

Most ASM students have the equipment necessary for these communications, although media are chosen partly for their accessibility. ASM tries to offer a balance of diverse material, some of potential interest to everyone as well as niche cultural nights. There is more development of unique communication material and heavy reliance on social media: Facebook and Instagram. Before COVID-19 ASM had no infrastructure for daily messages.

Initially, students were concerned about making friends and being able to talk to them but this worry has dissipated as they have acquired the habit of keeping in touch with each other. Student Affairs does frequent events and there are episodes each day of gatherings using Zoom (e.g., trivia nights and meeting rooms). Zoom has proved to be excellent because it can cope with large groups, it is versatile, and it works. As was noted in China, where students are notoriously reluctant to speak up in class, ASM found that the online world encourages students who used not to participate in discussions to do so (Lau et al, 2020). A wide range of additional events is under consideration going forward, including group movie nights.

In this work, Communications works closely with the registrar, for official and administrative information, with Student Affairs and with the student ambassadors. These are high-performing students who determine the agendas for student nights and keep their fingers on the pulse of the student body.

Going into the COVID-19 pandemic ASM had the advantage of competent and motivated faculty and harmonious relations within the institution based on a learning culture. The VPA has given strong leadership by holding a faculty forum each week. It was not difficult to motivate faculty members to acquire new skills, although a stipend was given for the first BBB training session, attracting 60 people. Subsequent ‘best-practice’ and drop-in sessions were also well attended.

ASM has a tradition of nurturing and team leadership at programme level. Most faculty are also affiliated with other local universities and professional associations and draw on these connections for professional development. Social get-togethers of the very diverse programme faculty members (25 nationalities) to share national music help to bond the group and encourage identification with ASM as a good place to work.

At the institutional level, while providing general professional development and training, ASM has also provided individualised training and support, including several peer coaches. It has been important for faculty to become proficient in both BBB and Zoom because of technical difficulties with both. MS Teams is also under consideration since the times require flexibility. Some faculty have adapted to the new instructional environment very successfully, others have faced greater challenges adjusting from their traditional face-to-face delivery style. There is occasional resistance from those who are already heavily invested in a particular technology. But by now, most faculty know the broad strokes of the technology and want details – such as how to pre-record video. The current challenge is group presentations, because camera sharing is sometimes a problem.

Institutional guides and regular e-mail updates have been important. Faculty drop-in sessions worked well because attendees could share their experiences and they also helped to break down the barriers between departments. A ‘Moodle Stars’ programme has been instituted by designating instructors who are available to teach this technology to colleagues.

Faculty, like many people during the pandemic, have work life and home life in the same place at the same time, which is difficult. In future, ASM may need to help faculty to acquire equipment to help them deliver classes online more effectively.

As one colleague remarked, quoting Sir Richard Branson: “You should train them well so that they can leave, but you should treat them well so that they want to stay.”

The president holds a drop-in session with students every week, which have provided an opportunity for ASM to receive feedback on student experiences and to respond quickly to any issues that may arise. Students in countries such as India and the Philippines have also participated regularly, joining in at night from their home countries.

When COVID-19 struck, most students were at first lost, nervous and scared. Much effort was invested in loosening them up and embedding humour in scheduled group sessions. This increased the interaction between students and created a “sense of community and confidence” (interviewee quotation). Students’ origins are highly diverse. Some had never previously touched a computer and had no understanding of the concept of plagiarism. Some do not have laptops and are using their phones. Basic personal hygiene and attitudes to women are sometimes a problem. Providing guidance and academic counselling is a challenge and helping students to become more independent takes time. But most students want to perform well because their futures are at stake. ASM must show empathy for students in diverse situations and, in future, may have to help students acquire laptops.

Financial hardship was a special focus in response planning. Students were worried about being able to afford to study. Many had lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Some, who depended on parents for funds, faced difficulties due to problems in their home countries, while others were anxious about being unable to support their families there. Some qualified for a Canadian federal support programme through unemployment insurance, or the CERB, but many did not qualify. In addition to its regular financial aid support budget, which is about $600,000/term, ASM introduced additional measures to assist students that provided an additional ~$100,000 in this term in direct special COVID-19 financial aid through:

Student Affairs aimed for a holistic integration of academic, social, psychological, physical, and informational support to students, by continuing what was already being done. The reality was that students were offered more events than on campus, where the availability of rooms had been a constraint. Zoom has proved good for live sessions; students take to it well and even engage in arguments. A combination of in-person and virtual events is called for after the COVID-19 restrictions lift. Live virtual events have been less successful than activities that students can do in their own time (e.g., quizzes and photo challenges).

Student Affairs has been doing more one-on-one work with the students off campus, many of them new students referred by their mentors or by the (very helpful) student ambassadors. Office hours for lower-level maths classes have been made mandatory and students are getting to like them.

More students are asking for help with learning, so a learning support session is offered every week on topics like time management or exams. These sessions would have attracted four or five students on campus but bring in about double that number online. When the session is later posted, many watch it because they like asynchronous material. These students never had access to specialist advice on learning in their previous education. Similarly, greater student participation was also found in the academic courses too.

ASM monitored student attendance closely throughout the term as an indicator of student engagement. The tracking reports have showed both a very high level of participation (higher than 90%) which has increased consistently each week. The current attendance rate is over 95% overall. Faculty have been doing an exceptional job of monitoring student progress and engagement, following up personally with students who were showing difficulty.

Despite all the positive feedback, some students are struggling. Some are not isolating and respecting physical distancing. They do not see online as social. Considerable efforts have been made to communicate information through email and social media channels to promote safe practices.

The student ambassadors, senior students who are part of a peer-advising programme, have played a strong role. ASM initiated a mentorship programme for new students this term and found that, with support from student ambassadors, first-year students, who tend to have higher levels of attrition, are seeking help more often. It expects that this individually focussed initiative will have a positive impact on retention and is considering extending it to upper-year students.

ASM students, faculty and staff have a strong sense of community, compassion and care, as they demonstrated in their support to a new student who had just arrived in Canada. The house in which she was living burned down and she not only lost all her belongings but also became homeless. The ASM community rallied around and raised $2,000 for her in days. “It is magical that people in this community are so eager to help” (interviewee quotation).

ASM owed its relative success in closing the campus and moving operations online to a combination of factors:

The big challenge for ASM and for HEIs worldwide is preparing for tomorrow. Various scenarios are under discussion in all countries and largely reflect forces and decisions beyond the control of higher education. High proportions of students in many HEIs — in ASM’s case a majority — come from countries with little reliable data about the impact of COVID-19. The timetable for recovery of the airline industry is unpredictable. Governments are making policy in the dark. For example, will the Government of Canada continue its benign policies on student visas and immigration if unemployment remains high after the pandemic? What will be the policies, orders and guidelines issued by Canada’s provinces, which have the main responsibility for education and health? Closer to home for ASM, what rules will the owner of the campus building apply and how might they constrain the use of classrooms?

Will students lose the ambition to study internationally? Higher education newsletters are full of speculation on this topic. Some argue that COVID-19 is a game-changer for higher education because international student mobility will decrease dramatically and teaching will move online.

Altbach and de Wit (2020), two well-respected scholars, comment on mobility:

Some institutions have become dependent on international student tuition fees as an important part of their financial survival. …The coronavirus crisis shows that this dependence is deeply problematic: it is likely that institutions dependent on this income will face significant problems.

And on changes of teaching methods following COVID-19:

But we are somewhat sceptical that what is being offered is of high quality or that students are very satisfied with the new situation. Most faculty members worldwide are not trained to offer distance courses, do not have the sophisticated technology necessary for high-quality teaching and learning and have not adapted their curricula to the web.

These challenges face HEIs both large and small. For example, “Monash University, by far Australia’s largest and most complex, is now facing a revenue shortfall this year of AU$350 million (US$226 million)” (Maslen, 2020).

Most HEIs are looking at variants of the three scenarios that are on the table at ASM: return to ‘normal’ (i.e., fully on campus); stay online; or go to a blended ‘semi-normal’ format. None of these scenarios provide easy answers.

The first, returning all students to fully face-to-face classes of their previous size is unlikely to be possible in most jurisdictions until at least 2021 because of physical distancing advice and restrictions issued by governments.

As to the second, for most HEIs fully online learning will not be a long-term solution for several reasons. In ASM’s case its mostly international students are looking for immersion in Canadian life. Elsewhere, HEIs have large investments in classrooms and campus facilities that are an important part of their image. Crucially, students were mostly unimpressed by their online experience in the early months of 2020 and will need financial or other incentives to repeat it after the pandemic. Moreover, converting a campus teaching HEI into a distance teaching institution requires major transformations of its structures, facilities and faculty organisation.

The third ‘blended’ option has its challenges too. Small face-to-face classes could be financially unsustainable. A combination of larger online lectures with smaller face-to-face tutorial groups to decrease classroom numbers may be an option. For ASM, the issue is not just the numbers in each class, but the overall number of students allowed on campus at the same time. To quote an interviewee: “opening the library could present challenges because students will want to congregate, meet and talk. Things will never be what they were, although people will be more open to online education.”

Most expect that ASM will use hybrid methods in future. Online will still be needed in the autumn of 2020 because people will still be fearful and some students may have to self-isolate from time to time. There could be various approaches: e.g., two classes of 15 instead of a class of 30, and staggered timings. Students will want both online and presence. A survey showed that ASM students split 55%/45% on whether online teaching had a positive or negative impact on course outcomes or academic quality. Going online with a new cohort of students will not be straightforward, because the current students knew each other from class, making online interaction easier.

Whatever the option chosen, with an enrolment that is 97% international, student recruitment is ASM’s central challenge (ICEF Monitor, 2020). In many countries prospective students (and their parents) are nervous about study abroad. Educational agents face difficulties with their offices shut down and potential students difficult to reach. Although there are students in the recruitment pipeline, the prospect of studying fully online makes them hesitate. In some countries, lockdowns closed banks so students could not make payments. Generally, it is not the restrictions imposed by Canada, but those imposed in the students’ countries of origin, that pose problems — with the exception of possible changes to Canadian policy on visas for online study. The prospect of enrolling in online courses in their home country might appeal to students as a more cost-effective way of starting their programme provided that, following announcements from Canada Immigration, it would not affect their eligibility for a post graduate work permit in Canada.

Fees are a challenge, too. In BC some institutions are adjusting their fees and incentive structures to attract international students. Some students expect a discount on fees for online programming, which is already allowed — if up to 50% of their programme can be taken online. In these circumstances being within the EduCo group is very helpful to ASM, whose staff consider that Australia is ten years ahead of Canada in its expertise on international student recruitment. EduCo understands the recruitment cycles and sees trends before they happen, enabling it to plan far ahead. “It knows how to recruit while being serious about academic quality” (interviewee quotation).

ASM’s recruitment work has the advantage that selling ‘the dream of Canada’ is still a good approach. There is an opportunity to divert students from the US as that country becomes less welcoming and struggles to deal with COVID-19. Some US HEIs are already in financial difficulties because losing one annual cohort of international students has a four-year impact on budgets. Canada’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and its treatment of international students is well regarded in international education markets, making the country well positioned for recovery.

In the post COVID-19 era, the Student Affairs function envisages both on-campus and online events and will get input about the optimal balance from the student ambassadors who meet weekly. They have many ideas and some put on events themselves. The new normal must be super fluid and try to prevent students from getting bored. Student leadership has become more prominent over the COVID-19 weeks and the student ambassadors are now thought of as an extension of Student Affairs. The orientation class will be made compulsory.

We conclude with two questions and some advice to HEIs worldwide as they face the post-COVID-19 era.

The first question is whether the emergency pivot to online operations induced by COVID-19 will have a durable effect on the way HEIs operate. Bates (2020a), a veteran observer of distance learning, has reviewed the “recent flurry of research on emergency remote learning” and notes “a suggestion in at least one report that many faculty and administrators do not believe that major changes to teaching and learning will result in the long run from the Covid-19 pivot”. He adds: “I don’t think I share that point of view.”

My interviewees at ASM do not share that view either. These are some of their comments: “this pandemic throws us 20 years into the future”; “things will never go back to normal”; “a lot of what we are doing will carry on”; “once consumer behaviour changes people don’t go back”; “COVID-19 forced us to become modern”; “we have had to make compromises and it has brought out the best in many people”; “the experience of working the institution through the transition has been extremely overwhelming but also really rewarding”; “we just had to do it”.

Assuming that the COVID-19 pivot does leave a lasting trace, the second question is what form any additional deployment of online or distance learning in HEIs will — or should — take. In another blog Bates (2020b) argues that: “half-measures are not going to work… Just moving your lectures online will only work once. What do you do for the next semester, and more importantly long-term?”

Avoiding half measures starts with the understanding that the revolutionary contribution of online and distance learning technologies is to make it possible to increase the scale and quality of teaching while also cutting costs. I have called this breaking open the “Iron Triangle”, (Daniel, 2010, p. 51). Technologies do this by creating economies of scale in the use of learning materials and by enabling people to study where and when they choose for much of the time. They allow HEIs to offer an appropriate blend of independent and interactive study (Daniel & Marquis, 1979).

The route to economies of scale in online learning for most HEIs is to assemble these courses in teams, drawing on the rapidly burgeoning pool of Open Educational Resources (OER) (Commonwealth of Learning, 2020), or other external resources and directing students to short, freely available courses such as MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses). This would ensure consistency and quality in the learning materials used and also allow for their asynchronous use by students independently. McKie (2020) reports on the huge take-up, by campus institutions, of online materials made available by distance-teaching organisations. For example, some 1,200 higher education institutions around the world are now using online courses from the French company Open Classrooms, reaching 120,000 students. In a similar vein, 30,000 people have enrolled in the FutureLearn course “How to Teach Online”. By incorporating externally sourced asynchronous learning materials into their courses, HEIs give greater freedom and flexibility to both faculty and students.

Students need both the flexibility of independent study and the support of interaction with their HEI and its teachers. A metaphor for online and distance education is a student sitting on a stool with three legs: learning materials; student support; and excellent logistics. If any leg is shaky the student will fall (fail). Successful online education means devoting as much energy and thought to organising student support and logistics as to developing the online course material.

Finally, in an era of more widespread online and distance learning, HEIs must become more open to collaboration with each other, while governments must facilitate such partnerships instead of pitting the HEIs against each other to compete for their share of state support — which will likely continue declining anyway. Ensuring fast broadband connectivity throughout its jurisdiction is clearly a task for the government, not individual HEIs. Earmarking some state funds for collaborative ventures, especially those with potential to break open the Iron Triangle, is a proven means for encouraging co-operation in pursuit of quality and scale instead of diluting the impact of resources by needless duplication.

Acsenda 19. (2019, November 27). Strategic Technology Plan. Acsenda School of Management.

Altbach, P., & De Wit, H. (2020, March 14). Covid-19: The internationalisation revolution that isn’t. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200312143728370

Bates, T. (2020a, July 27). Research reports on Covid-19 and emergency remote learning/online learning. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/07/27/research-reports-on-COVID-19-and-emergency-remote-learning-online-learning/

Bates, T. (2020b, April 26). Crashing into online learning: A report from five continents and some conclusions. Online Learning and Distance Education Resources. https://www.tonybates.ca/2020/04/26/crashing-into-online-learning-a-report-from-five-continents-and-some-conclusions/

Commonwealth of Learning. (2020). Open Educational Resources. https://www.col.org/programmes/open-educational-resources

Daniel, J. S. (2010). Mega-Schools, technology and teachers: Achieving education for all. Routledge.

Daniel, J. S. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

Daniel, J. S., & Marquis, C. (1979). Independence and Interaction: Getting the mixture right. Teaching at a Distance, 14, 29-44.

ICEF Monitor. (2020). New insights on how international students are planning for the coming academic year. https://monitor.icef.com/2020/05/new-insights-on-how-international-students-are-planning-for-the-coming-academic-year/

Lau, J., Yang, B., & Dasgupta, R. (2020). Will the coronavirus make online education go viral? The Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/will-coronavirus-make-online-education-go-viral

Maslen, G. (2020, May 7). Saving Australia’s biggest university. University World News.

https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200507090424381

McKie, A. (2020, April 14). Has the leap online changed higher education forever? The Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/has-leap-online-changed-higher-education-forever

UNESCO (2020). 1.37 billion students now home as COVID-19 school closures expand, ministers scale up multimedia approaches to ensure learning continuity. https://en.unesco.org/news/137-billion-students-now-home-COVID-19-school-closures-expand-ministers-scale-multimedia

Author:

Sir John Daniel is the Chancellor, Acsenda School of Management, Vancouver, Canada. His previous appointments include: president – Laurentian University, Canada; vice-chancellor – UK Open University; Assistant Director-General – UNESCO; and president – The Commonwealth of Learning. His 400 publications include the books: Mega-universities and knowledge media: Technology strategies for higher education and mega-schools, technology and teachers: Achieving Education for All. Email: sirjohnbapu@gmail.com

Cite this paper as: Daniel, J. S. (2020). COVID-19 – A two-week transition from campus to online at the Acsenda School of Management, Canada. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(3), 271-285.