2020 VOL. 7, No. 1

Abstract: This paper explores cultural inclusivity in online learning design by discussing two international capacity development projects: an online tutor mentor development program in Sri Lanka and a hybrid physician assistant training program in Ghana. Inclusivity involves establishing partnerships and conducting needs assessments to maximise the capacity that already exists within a given context, and addressing cultural factors that impact online learning — developing a learning community, negotiating identity, power, and authority, generating social presence, supporting collaboration, engaging in authentic inquiry-based learning, navigating interactions in a second language, and developing co-mentoring relationships to support learning. The paper provides a framework, WisCom (Wisdom Communities) to guide the design of culturally inclusive online learning incorporating lessons learned from international projects. By emphasizing divergent thinking, consensus building, and the exploration of multiple solutions to complex, real-world problems, WisCom maximises opportunities for participants’ diverse backgrounds and experiences to be valued.

Keywords: online learning, cultural inclusivity, culturally inclusive learning design, international partnerships, capacity development.

Capacity development projects in international contexts, either funded by donor agencies or local governments, are increasingly relying on digitalization to achieve educational goals in both formal and non-formal sectors. A global survey of higher education institutions spanning all continents, more than 30 countries and 69 cases, concluded that: “Digital technology has become near ubiquitous in many countries today or is on a path to reach this state in the near future” (Orr, Weller & Farrow, 2018, p. 8). The overall findings indicate that most higher education providers are just at the beginning of developing comprehensive strategies for harnessing digitalization, and are adopting technology, open, and online approaches in a variety of ways to meet a diverse set of needs. Signaling a change that could reshape education delivery in the country, the government of India for the first time announced that it is allowing universities to offer fully online degrees (McKenzie, 2020).

The Bologna Digital 2020 white paper (Rampelt, Orr & Knoth, 2019) points out that, in 2030, universities and colleges of higher education in Europe will offer courses of study that are much more flexible and provide different learning pathways recognizing the diversity of the student population. “The university will be a networked and open institution in 2030, which cooperates much more closely with other universities as well as the community and jointly develops and provides educational programmes” (p. 4). The 2019 Educause Horizon Report (Alexander et al, 2019) which summarises trends and challenges that will shape the adoption of technology in higher education in the United States of America (US), has echoed the significance of digitalization and calls our attention to themes such as digital equity, digital literacy, the redesign of learning spaces to include authentic, active learning, blended learning designs, increasing diversity of the global student population, the significance of lifelong learning, and the value of collaboration in communities of practice.

Yet, while digital technology has connected us and enabled more people from more places to learn together, educators have yet to offer access, affordability, and inclusion in international contexts. Given the trend toward digitalization, educators need to ask what constitutes an equitable and inclusive online learning experience. Resta, Laferrière, McLaughlin and Kouraogo (2018) note that digital equity is more than access to computers, software, and connectivity. It also includes access to: meaningful, and culturally relevant content in local languages; creating, sharing, and exchanging digital content; educators who know how to use digital tools and resources; and research on the application of digital technologies to improve learning. From their experience conducting a global online master’s degree program, Rye and Støkken (2012) observe that online education, rather than creating a new space of equality, amplified the differences between local contexts and the inequalities between participants from Norway, Ghana, and Uganda. They advocate recognizing students’ local context as a significant part of their educational space. While many factors contribute to attrition in online programs, at the top of the list are low levels of interaction and support (Ludwig-Hardman & Dunlap, 2003). Based on a systematic review of literature on Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) from 2014 to 2018, Lambert (2019) calls for additional attention to and research on inclusive design and pedagogy for online learning if MOOCs and other free open education programs are to provide equitable forms of online education.

Focusing on inclusion as a hallmark of quality online learning supports the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal #4 (2015), which, “emphasises inclusion and equity as laying foundations for quality education and learning” (Tang, 2017). UNESCO (2017) has defined inclusion as, “a process that helps to overcome barriers limiting the presence, participation and achievement of learners” (p. 7), and equity as “ensuring that there is a concern with fairness, such that the education of all learners is seen as being of equal importance” (p. 7). One approach to examining inclusion and equity is through a cultural lens.

In this paper I focus on the concept of inclusion from a cultural perspective. The question I seek to address is: How can we design culturally inclusive online learning environments that ensure the presence, participation, and achievement of diverse learners from diverse sociocultural contexts? To address this question, I begin by defining culture and cultural inclusivity, and the relationship between culture and capacity development. Next, I discuss two international capacity development projects where I learned important lessons about designing for inclusivity and equity. I conclude by providing guidance for designing culturally inclusive online learning environments. In order to do so, I have organised this paper into two parts. In Part I, I discuss the two international projects and partnerships, one in Sri Lanka and the other in Ghana, where online learning was used for capacity development in the education and health sectors. I reflect on lessons learned from my attempts to design and implement inclusive online learning environments. In Part II, I share an online design framework, WisCom or Wisdom Communities, that can guide the development of culturally inclusive learning environments my colleagues and I have developed, incorporating lessons learned from the two international projects and several years of our collective experience designing and teaching online in diverse sociocultural contexts (Gunawardena, Frechette, & Layne, 2019).

Culture is a complex concept to define. Hall (1959) showed the complex interplay between culture and communication when he stated: “culture is communication and communication is culture” (p. 186). A frequently used conceptual framework for understanding culture is the dimensional framework developed by Hofstede (1980) who identified four types of cultural differences at the national level: individualism-collectivism, power distance, masculinity-femininity, and uncertainty avoidance. Hall (1976) identified another bipolar dimension, high-context and low-context communication styles and implied indirect and direct communication. Context is important to understanding a message in a high-context culture, where much remains unsaid. In low–context cultures, people communicate more directly and explicitly by encoding meaning in the words they utter.

Several researchers have pointed out the limitations of these bipolar dimensional frameworks to explain cultural differences when communication takes place online (Ess, 2009; Goodfellow & Lamy, 2009). Goodfellow and Hewling (2005) have advocated a move away from these “essentialist” frameworks to a more “negotiated” view of culture as being negotiated online by diverse participants. A negotiated perspective views the Internet as a culture in its own right, blurring the boundaries between the real and virtual worlds.

We have defined culture as a “collection of shared perceptions of the world and our place in it” (Gunawardena, Frechette & Layne, 2019, p. 3). Our values and beliefs affect identity formation, communication, and roles in society. Each of us belongs to many tribes, and our memberships overlap, sometimes in unusual ways. “Online cultures can be just as real as their analog counterparts, but they allow ideas to traverse spatial and temporal barriers in ways that generate novel values and beliefs. This cross-pollination of ideas continually generates new cultural norms. Cultures persist by way of interaction” (p. 3). While interaction can generate different ways of seeing the world, it does not guarantee that these views will be heard, appreciated, and valued. To truly capitalise on diversity, we have to focus on inclusivity and equity. Inclusion fosters a sense of belonging to a community—feeling appreciated for one’s unique characteristics, perspectives, contributions, and ways of thinking. Participants feel comfortable sharing their ideas, their identities, cultures, languages, and ways of seeing the world.

Culture is inextricably linked to capacity development. Sustainable capacity development calls for understanding culture and context by listening to, learning about, and building trust with people and communities. Capacity development is “an approach that builds on existing skills and knowledge, driving a dynamic and flexible process of change, borne by local actors” (Zamfir, 2017, p. 1). It is crucial that local actors who understand the sociocultural context identify the needs for which they want the project, design the process of change they envision, and manage and evaluate it. External partners can only support the project with the skills needed and not available in the local context. Local actors must own the project if it is to become sustainable.

Capacity development can be approached from a “social embeddedness perspective” or a “transfer and diffusion perspective” (Avgerou, 2010). A social embedded perspective considers distinctive features of a cultural context, such as attitudes to hierarchy, sense of space, work ethic; while a transfer and diffusion perspective implies transferring technology applications from a Western to a non-Western culture, and oversimplifies cultural differences (Avgerou, 2010). A social embeddedness perspective, therefore, can lead to sustainable capacity development. Once a need has been established for online learning by local actors, a continuing concern should be centered on how to design, develop and implement online learning that is appropriate for the cultural context accommodating the values, needs, educational expectations and learning preferences of diverse learners and educational systems that currently exist. Next, I explore culture and cultural inclusivity in two international capacity development projects.

In this section, I discuss selected aspects of two international projects, one in Sri Lanka and the other in Ghana, where online learning was identified by local actors as the means to develop existing capacities for delivering much needed education and training. In Sri Lanka, I worked as a short-term international consultant for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) funded project, and volunteered as a consultant for the project in Ghana for which we obtained funds from a Canadian government donor agency.

Sri Lanka is the country of my birth and heritage, and, therefore, even though I joined the project as an international consultant, I was familiar with the cultural context and spoke one of the native languages, which enabled me to build rapport. By this time, I had lived in the US for over twenty-five years and had integrated a Western mindset, a way of communication and doing things which sometimes clashed with my Sri Lankan heritage. I often needed to reflect on this clash of cultures within me and seek input from others as to how I was doing. Ghana was a new cultural experience for me. Communication in English enabled us to get to know our project participants and the context at a distance, but it was difficult to decipher the intrinsic nuances of the cultural context till we went to Ghana to implement the project.

Adopting a social embeddedness perspective, I discuss my experiences from the perspective of a North American partner open to learning important cultural lessons in a given context. I am keenly aware of the power differentials that exist when one is considered an international consultant or expert and have tried my best to be open and flexible in my approach to learn from my local partners. My intention has always been to develop the capacity and talent that already exists in the local context. I discuss the two projects from a position of cultural humility (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998), knowing full well that one can never really get at the cultural nuances and complexity that are present in the contexts in which one carries out the projects. The adoption of a cultural humility stance and openness to learning and flexibility was the best approach to working in Sri Lanka and Ghana.

To address the need to provide higher education opportunities for a large proportion of students who qualify for university admission but are denied access to traditional universities, the government of Sri Lanka funded a six-year Distance Education Modernization Project (DEMP) to develop a National Online Distance Education Service (NODES) implemented by the Ministry of Higher Education through a loan obtained from the Asian Development Bank (Liyanage, Pasqual & Wright, 2010). DEMP was tasked with providing training and development on the design and delivery of online education to universities and professional organizations that were selected to offer degree and diploma programs through NODES. My task as an international consultant for the Canadian company that implement the project in Sri Lanka was to develop academic faculty in universities and trainers in professional organizations (such as the Banker’s Institute and Library Association), on the skills of online tutoring and mentoring as they would be expected to facilitate the courses that would be offered through NODES. The participants in this training (faculty and trainers) will be hereafter collectively referred to as “faculty.”

Building Partnerships

I have learned that a vital approach to working on donor funded large-scale international projects is to build trustworthy collaborative partnerships in the local context. The term “partnership” has been defined as a collaborative relationship between two or more parties “with the intent of accomplishing mutually compatible goals that would be difficult for each to accomplish alone” (Spekman, Isabella & MacAvoy, 2000, p. 37). The interdependence of the relationship is at the core of a partnership without which it would be difficult for either party to achieve the planned goals.

When I began my consultancy as a Tutor Mentor Specialist in 2006, I was paired with two local co-consultants, who were faculty members in computer science and telecommunications from a leading Sri Lankan university. They were experts on managing the open source Moodle Learning Management system (LMS) that had been selected as the platform. This partnership between international and local consultants enabled us to complement our skills, theirs in Moodle and mine in adult learning and online instructional design, as we planned the best possible means for capacity development. While the three of us worked as a team, we developed close collaborative relationships with the other international and national consultants as well as our faculty participants. These collaborative partnerships coupled with the visionary local team leader who moved us toward our collective goals, enabled us to develop and implement a sustainable online tutor mentor training workshop on the Moodle platform.

Needs Assessment

The sustainability of a capacity development program depends on not only good partnerships but also on a sound needs assessment to understand what is actually needed in a specific sociocultural context. As online learning was new in the Sri Lankan context, our needs assessment indicated the importance of engaging faculty as students in online learning experiences so they see their roles as tutors and mentors from the students’ point of view. To meet this need, we developed a 14-module, online tutor mentor training workshop using the Moodle LMS. We offered this training over a period of three weeks in a hybrid format, with an initial face-to-face meeting followed by a week of online activities, another face-to-face meeting followed by two weeks of online activities predominantly focused on cross-cultural e-mentoring, and a final face-to-face meeting to conclude the workshop. We felt that this was the best format to accommodate the needs of the learners. In the Sri Lankan context, the initial face-to-face interaction was critical to build rapport and trust between the trainers and participants.

The sustainability of the online tutor mentor workshop became evident only after I completed my consultancy and returned to the US The tutor mentors we had trained began training new cohorts of participants. The online workshop we had developed was used in different formats to suit the needs of diverse training cohorts. The major success was the Open University of Sri Lanka’s attempt to offer this workshop transnationally to participants in Sri Lanka, Mauritius, and Pakistan (Jayatilleke, Kulasekara, Kumarasinha & Gunawardena, 2017). The tutor mentor workshop was sustainable mostly because we took the trouble to establish meaningful collaborative partnerships, understood what was needed in the local context, and supported each other in the implementation of the workshop. The Sri Lankan faculty participants highly valued the cross-cultural e-mentoring partnership between them and my graduate students at the University of New Mexico, which was established to demonstrate the networked nature of online learning, and how culturally inclusive designs could capitalise on the diversity of its participants while at the same time providing much needed mentoring and support for novice online learners (Jayatilleke, Kulasekara, Kumarasinha & Gunawardena, 2012). I discuss this partnership next.

The Cross-Cultural E-mentoring Partnership

E-mentoring which merges mentoring with electronic communications is a reciprocal learning partnership between mentors and mentees to develop skills, knowledge, confidence, and cultural understanding (Single & Muller, 2001). The e-mentoring relationship between Sri Lankan faculty participants and graduate students at UNM in the US was set up as a collaborative, equitable partnership where both parties would learn from each other. In this context, because UNM graduate students had experience facilitating online learning and conducting inquiry-based learning online, they assumed the role of e-mentors, and Sri Lankan faculty, because they were new to online learning, became mentees. The UNM graduate students volunteered their time for this activity with the intention of learning through this collaborate partnership how to mentor and support learners across cultures.

Participants in each online workshop (approximately 30) were divided into small groups of 10-12 participants, and one e-mentor was assigned to each small group to engage in an inquiry-based learning (IBL) activity. IBL grounded in constructivist learning theory, views learning as the process of constructing meaning by questioning, critical thinking and problem solving, while helping participants to communicate with those who hold diverse perspectives, and to collaborate with others in finding solutions to complex problems (Gunawardena, 2004). Each group was assigned one of three IBL activities based on authentic social problems in the capitol city of Colombo in Sri Lanka: a problem solving activity to clean up garbage, a role-play activity to solve traffic congestion, and a case-based reasoning activity to find a solution for street children. Faculty participants could employ their diverse disciplinary perspectives to solve a common problem that impacted them. They were encouraged to create awareness of the Sri Lankan sociocultural context for the e-mentor so that the learning experience will be beneficial to both parties. The final expected product was a paper outlining the process used to resolve the assigned problem and the proposed resolution, a paper that could be submitted to the mayor of the city. Tools used for collaboration in Moodle were asynchronous discussion forums and a wiki for report writing.

I focus my attention on five design elements that supported inclusivity in this e-mentoring partnership: (1) negotiating identity and generating social presence, (2) developing an online learning community, (3) engaging in inquiry-based learning and social construction of knowledge, (4) negotiating interactions in a second language and (5) e-mentoring.

Negotiating Identity and Generating Social Presence

Both professional and personal identity negotiation online play an essential role in building trust. Identity is often negotiated through self-disclosure and storytelling. Individuals differ in the way they create identity and negotiate it with others. Some focus on regional or tribal identity, others on national or organizational identity. Identity presentation is important as this is the first step to building an online community. Sri Lankan faculty participants were supported to introduce themselves online by providing guidance on what points to address in the introduction (such as professional identity and personal life). When the instructor/facilitator introduces himself/herself following these same guidelines, participants are more apt to feel comfortable and follow the lead. Rather than depending on a static biography posted online, the facilitator should present himself/herself as a human being and thus generate social presence and rapport. For example, as the lead facilitator, I introduced myself as a “global nomad” living between two or more cultures, but, belonging to none. I discussed my international mobility and experiences which have had a profound impact on my life, my identity and ability to adapt to other cultural contexts. Participants are more likely to self-disclose when they feel they can relate to the facilitator. To support students who are reluctant to post their introductions online, one technique we have adopted in cross-cultural collaborations is to have a student from one country get to know a student from another, and then present each other online. This reduces the stress of presenting one’s persona and identity to an unknown online group. Another technique is to make posting photographs optional, and instead ask learners to post an image that represents them and say why it does so. We used this technique of posting images, rather than photographs, which was preferable in the Sri Lankan context.

When the US e-mentors were introduced to the three IBL groups, they appreciated the personal introductions already made by Sri Lankan mentees and followed the same guidelines to post their introductions (LaPointe et al, 2008). E-mentors mentioned the helpfulness of the user profiles in increasing social presence — “the degree to which a person is perceived as a ‘real person’ in mediated communication” (Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997). Social presence is closely related to identity expression. Through their self-disclosure, both mentees and e-mentors generated identity and social presence. One e-mentor mentioned that she often reread the profile of the mentees so that she could better understand their background (LaPointe, 2008). We felt that by not using photographs, learners and e-mentors alike did not have to be judged based on their physical appearance.

Developing an Online Learning Community

As opposed to hierarchical, teacher controlled learning environments, inclusive learning environments must foster a sense of belonging to and participation in a learning community. Therefore, both e-mentors and mentees were asked to engage in building community. During the first week of the IBL activity, the mentees welcomed the e-mentor and oriented the e-mentor to the composition of the group, task, and sociocultural context. The e-mentors soon established rapport in some cases through informal conversation in the virtual canteen/virtual café. This seemed to bring the participants closer to one another as humor and fun were often associated with these informal exchanges, thereby, creating a more relaxed and conducive atmosphere for learning. For example, it was fun to advise a US e-mentor on what to eat for breakfast in Sri Lanka, e.g., kiribath (milk rice) with jaggery (solidified honey) or string hoppers with fish curry, etc. In turn, the US mentor explained what they would eat for breakfast in New Mexico. While the virtual canteen provided a forum to break the ice, e-mentors often reached out to mentees via email, a more private way to encourage them to participate in the discussion forums. This communication method was effective as it was easier for a mentee who was new to the online environment to communicate in private rather than in a public forum where the mentee might feel embarrassed.

E-mentors initiated the IBL learning activity by setting the context and clearly defining the expectations. They often began on a positive note reaching out to the mentees:

Hello! It is a pleasure to have this opportunity to work with you all. I am very interested in mentoring and coaching in distance education environments. I feel fortunate to be able to make so many new acquaintances that are interested in similar pursuits... (E-mentor, Round 3, Group 2, Forum 1, Post 1, Gunawardena, et al 2011).

Personal anecdotes helped both e-mentors and mentees illustrate cultural aspects relevant to the case discussed such as the homeless issues in their respective countries. By observing the skills demonstrated by e-mentors, mentees learned essential skills for online learning, tutoring and mentoring such as moderating, negotiation, team building, sharing multiple perspectives and valuing each other's ideas and beliefs, (Gunawardena et al, 2011).

The mentees seemed to get on better with those e-mentors who built community among the group, spent more time in the forum, provided timely advice for completing tasks, and guided them to achieve their goals. Sometimes the absence of an e-mentor from the scene ‘worried’ the group such as when an e-mentor was not available due to personal reasons and a substitute e-mentor was announced. The interdependency established between the e-mentor and mentees led to fruitful collaboration (La Pointe, 2008).

Inquiry-based Learning and Social Construction of Knowledge

Our analysis of the online case-based reasoning IBL activity across three rounds of the online Tutor Mentor workshop using the Interaction Analysis Model (IAM) (Gunawardena, Lowe & Anderson, 1997), illustrated that social construction of knowledge occurred a number of times in all three rounds. One remarkable finding that could be attributed to a cultural difference is that we rarely observed phases of dissonance or disagreement with other points of view during the process of knowledge construction as stipulated by IAM. The Sri Lankan participants were polite and did not openly disagree at the level of ideas but moved to negotiation of meaning and co-construction of new knowledge based on consensus building. Therefore, we had to re-define 'dissonance' as specified in the IAM in cultural terms (Gunawardena, et al, 2013).

This process of using consensus to engage in knowledge construction is very different from some of the prominent Western perspectives on building knowledge which puts emphasis on debate and argumentation. “Learning to argue represents an important way of thinking that facilitates conceptual change and is essential for problem solving” (Jonassen & Kim, 2010, p. 439). Biesenbach-Lucas (2003) in her survey of communication conventions of native and non-native speakers in online discussions, notes that the lack of challenge and disagreement of ideas in Asian learners is troubling as it is the “resolution of such areas of agreement and disagreement that ‘results in higher forms of reasoning’ because ‘cognitive development requires that individuals encounter others who contradict their own intuitively derived ideas” (p. 37). These two perspectives (Jonassen & Kim, 2010; Biesenbach-Lucas, 2003) on knowledge construction primarily support a Western point of view. In his study of a global e-mail debate on intercultural communication, Chen (2000) showed that the debate format caused orientation problems for some participants, as the “debate” is a product of low-context culture that requires a direct expression of one’s argument by using logical reasoning. Many students in Asian and Latin American contexts find an argumentative format uncomfortable in an academic context, and this discomfort is exacerbated when the debate is facilitated through a medium devoid of nonverbal cues. Sri Lankan participants built consensus when they were confronted with two opposing points of view, often trying to determine to what degree they could support the opposing point of view (Gunawardena et al, 2013). This process of consensus building was also supported by Lopez-Islas (2001) in his analysis of knowledge construction using IAM in online discussion forums at Monterrey Tech-Virtual University in Mexico. He observed that open disagreement with ideas expressed by others is not appropriate in the Mexican cultural context, and, therefore, participants moved to knowledge construction without moving through the cognitive dissonance phase as described in the IAM. Scardamalia and Bereiter (2006) found that in knowledge building, adversarial argumentation has a role, but it is collaborative discourse that is the driver of creative knowledge work. Therefore, when designing for cultural inclusivity, we need to be cognizant of knowledge building processes in diverse cultural contexts.

The process of negotiation and social construction of knowledge supported by an e-mentor led to perspective transformations. Participants gained new insights concerning: (a) the value of well-designed online learning; (b) themselves (self-image, self-efficacy) as being able to learn online; and (c) the people directly impacted by the societal problems they solved. Participants' new insights were accompanied by changes in perspectives and increased caring about the problems and people involved. Participants began to see themselves as part of the solution (LaPointe et al, 2008). The following is an example of a participant’s post in response to the e-mentor’s personal story about street children, as the group engaged in case-based reasoning:

Actually we see street children every day and sometimes regard them as "nuisance". When we were assigned to do this as a group activity, I was thinking what to write! After discussing this topic for one week, I think all of us got interested and see the real picture of street children and really wanted to do something for them by actually doing! So thank you… for inspiring us! I think all of us will see them differently when we meet them next time. As a result of this learning issue let us get together and try to help them not only online but in a real situation (Jayatilleke et al, 2012, p. 66).

Mentors can play a key role in supporting interaction and knowledge construction by orienting learners to diverse ways of constructing knowledge, inviting learners to participate in discussions, and using motivational strategies and scaffolds to promote collaborative construction of knowledge. Co-mentoring relationships can be set up between peers, peers and facilitators, and between peers and community experts thus broadening the expertise brought into the learning experience.

Negotiating Interactions in a Second Language

Students need support to adjust to technology-based modes of communication.

Since online communication requires self-expression in written text, this is often overwhelming and challenging to those from indigenous or oral cultures. It is particularly challenging for those who consider themselves poor writers and those who use a second language to communicate. In some instances, lack of participation in the IBL activities was due to a participant’s perception of his or her inadequacy in the use of English. In other instances, the asynchronous format afforded an advantage by allowing these learners time to think and post their responses. English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners, for example, need additional time to read, consult dictionaries, and peruse content provided in a variety of formats such as written lectures, audio recordings, and concept maps.

Since language is a critical factor in the negotiation of meaning in an online community, designers must post specific communication protocols or netiquette appropriate to the context to guide interaction. Netiquette can provide guidance on how to communicate in public social spaces. It also serves as a referent point to encourage civil discourse, resolve conflict, and discourage flaming. Allowing for translanguaging among bi-lingual participants is another technique that can be used to create an inclusive community. ‘‘Translanguaging is the process of making meaning, shaping experiences, gaining understanding and knowledge through the use of two languages’’ (Baker, 2011, p. 288). Ratwatte (2014) notes that in Sri Lanka translanguaging is the norm, and that collective scaffolding through the process of translanguaging enables learners to engage with the second language at a deeper level than would be possible by using only one language. Therefore, providing guidance for communication online, and encouraging translanguaging when the interacting group knows both languages, are ways to design inclusive online learning environments.

E-mentoring and E-Mentor Roles

E-mentors played an important role in contributing to both community and knowledge building among online participants during the three IBL activities (LaPointe et al, 2008). Transcript analysis of the IBL activities showed that the US e-mentors demonstrated six types of facilitating techniques to help the mentees in Sri Lanka build a learning community and construct knowledge within the three IBL designs. These included: (1) social (greetings), (2) pedagogical (guidance, questioning), (3) managerial (assigning roles stipulating time), (4) technical (troubleshooting), (5) collaborative (team building), and (6) inspirational (when mentees indicated interactions with the e-mentor changed their way of thinking) (Jayatilleke, Kulasekera, Kumarasinha & Gunawardena, 2012).

E-mentors prompted mentees to move beyond participation in solving the problem/case assigned to the group, and reflect on their own learning process and support needs in the online environment. We observed a difference in the way US and Sri Lankan e-mentors conducted the IBL activities. The US e-mentors encouraged the mentees indirectly to think through the problem and come up with their own solutions, while the Sri Lankan e-mentors appeared to provide more direct advice on how to solve the problem. This could be related to the expectation for direct guidance from the teacher in the Sri Lankan context (LaPointe et al, 2008).

An unexpected and dynamic finding of this e-mentoring partnership was the cross-cultural learning experiences reported by the US e-mentors after they facilitated the IBL activity. During a focus group to discuss their experiences, e-mentors stated that they had to learn how to understand and respect the different cultural perspectives and backgrounds that existed within the mentee group. The “disorienting dilemma" of entering a new culture online and a new mode of mentoring and coaching called for critical reflection on their role as e-mentors, which in turn transformed perspectives (LaPointe et al, 2008). E-mentors observed that mentees treated them with a great deal of respect and courtesy, and did not directly challenge their point of view. The mentees took pride in maintaining a positive impression for the e-mentor, often encouraging colleagues to contribute so as not to let the e-mentor down. Even though there was a significant time difference (approximately 12 hours) where mentees had to wait for a response from the e-mentor, each group appreciated the opportunity to interact with an international mentor who volunteered time to guide them through the learning process. E-mentors observed that they functioned well when they were mentored into the process of e-mentoring across cultures. In addition, having a network of other e-mentors they could rely on to discuss ideas and mentoring techniques, fostered confidence in the task (Gunawardena et al, 2008). The e-mentoring partnership not only maximised the networking capability of the medium but also created an inclusive learning environment where diverse participants learned from multiple perspectives shared and the online mentoring and tutoring strategies employed.

I transition now to discuss another partnership, a capacity development project to enhance the skills of physician assistants in Ghana. I consider this to be a student-centered project as my students led this project and volunteered their time and effort to design and implement the training solution.

“The greatest challenge for Africa’s Internet connectivity is not access, but content because there is a dearth of information for Africa from Africa” (Madzingira, 2001, p. 12). The project in Ghana began to address this need, and in response to a request for assistance from a Ghanaian physician who wanted to develop a distance learning component to his existing physician assistant (PA) program that was offered on campus to a limited number of students at a Ghanaian University (hereafter referred to as GU). The target students would be practicing PAs who were serving rural communities spread throughout Ghana. They shoulder responsibility for the health care of a large percentage of the rural Ghanaian population.

I undertook this project as I felt this request from the physician, (hereafter referred to as Ghanaian Lead) provided a challenging learning opportunity for my students and I at the University of New Mexico to design and develop remotely a distance education program to serve the needs in an unfamiliar cultural context. During the three years following the request in 2010, I assigned this learning experience as a group project in my “Culture and Global eLearning” graduate class taught online. When one group of students completed the class, they would serve as mentors to students who undertook this project in the following semester. In every class, my students and I worked with the Ghanaian Lead to determine needs, develop and test distance learning prototypes, and consider how this approach to learning would be accepted in the Ghanaian sociocultural context. When a distance learning solution became a viable option, we assembled an international, interdisciplinary project team consisting of Ghanaian, Canadian, and US partners to secure funding for a blended learning solution to provide continuing education for PAs in Ghana. Four of my graduate students who had worked on this project volunteered to take the lead to write the grant proposal and produce a three-minute video segment that was required by the funding agency. Our project team was successful in securing funds in 2013 from a Canadian government supported funding agency to implement this blended learning solution in Ghana using mobile interface friendly courseware that resided in the GU’s Moodle platform, which would be accessed using mobile tablets and phones. The program would also be supported by face-to-face clinical practice during the summer.

The GU directly received funding for this project from the Canadian agency, and the Ghanaian Lead served as the project director. The US and Canadian partners volunteered their time and effort on the project and received a travel allowance to support the implementation of this project in Ghana. The North American partners included six graduate students at UNM majoring in eLearning, and two Canadian faculty members, whose expertise was in mobile learning. The North American partners were a multicultural team representing American, Canadian, South Asian, African, Eastern European and South American cultural heritages. The Ghanaian partners consisted of the Ghanaian Lead physician who was the Head of the PA program and his faculty, Information Technology (IT) staff in charge of the Moodle platform, and Administrative Assistants. The main goal of the volunteer North American partners was to assist the GU in the design and development of the online and mobile learning component of the PA program, hereafter referred to as the blended learning program. The Ghanaian subject matter experts generated and provided the content of the courses we designed online so that it could be an educational program relevant to the needs of the Ghanaian socio-cultural context.

Developing the Partnership

Our initial effort as North American partners was relationship-building, and understanding the project from the Ghanaian point of view. While the Ghanaian Lead and I met initially face-to-face at a conference when the request for my assistance was made, the extended negotiation of identity across team members occurred through electronic media (predominantly Skype) when we met weekly to plan, design and implement the project. However, it was not until our visit to Ghana that we realised the key role that tribal identity and tribal affiliation played in the lives of Ghanaian people. As with many African countries, tribal identities remain entrenched in people’s consciousness, and play a role in organizations, politics, and education. In organizations, individuals tend to gravitate more towards fellow tribe members or people from their region. Those in authority cement their power by surrounding themselves with relatives, tribesmen, and clansmen to ensure their power is consolidated. Tribal consciousness came into play in hiring decisions as those from one’s own tribe were considered to be more supportive of one’s decisions and goals even though they might not be adequately qualified for the position. The North American team with its well-prepared job descriptions to hire the most qualified project personnel, had to negotiate with the Ghanaian Lead’s tribal affiliations and eventually supported his decisions for hire.

Hall’s (1976) conceptualization of high context and low context communication styles, and implied indirect and direct communication, was useful for reflecting on our cross-cultural interactions. While the North American partners employed direct communication and often communicated both orally and in writing as we were developing the project, the Ghanaian partners were more indirect in their communication and mostly communicated orally, and at times through email. In a predominantly oral culture, meanings expressed are highly specific and local, and the North American partners lacked that local knowledge to understand the intent of the communications and its connotations. While online communication tools (Skype, Dropbox, and Wiggio) proved to be very effective in planning and design, we missed out on understanding the local context by performing most of the activities remotely. We felt that we did not get a true picture of the situation on the ground, since junior Ghanaian partners, having to maintain harmonious relationships, had difficulty communicating directly with us. While communication was challenging, non-communication was even more perplexing. We often encountered silent periods in our planning process and wondered about the meaning of this silence, and its intended communication.

Needs Assessment and Educational Expectations

Our needs assessment with prospective PA students conducted in Ghana, highlighted the value placed on family and relationships where family is a strong bond and a main source of identity, responsibility and loyalty. Communication had to be understood within the context of these relationships. Contextual as well as relational information was key to understanding a message and its meaning. PAs provided insight on how to design the mobile and blended learning environment that would help them shift from a traditional hierarchical learning space to a more egalitarian interactive space (Palalas et al, 2015). Ghanaian students shared why online courses may be better. They said that those who are less fluent in English and reluctant to speak the language in face-to-face contexts are more likely to feel comfortable expressing themselves in the anonymity of the online environment where they can take time, reflect and edit. Students felt that introverts are more likely to put forward their opinions as the online environment is more welcoming and comforting.

PA students discussed the importance of conducting an orientation session to orient them to mobile and online learning, self-directed independent learning, learning how to learn skills, and training in the use of technology. In addition, students’ requested avenues for visual and auditory learning preferences in course design and the incorporation of traditional culture, symbols and proverbs in the web interface. Clear goals and expectations, as well as structure in the organization of the course were additional requests. These insights helped us to design an orientation program to address their needs, which was conducted in Ghana by UNM graduate students.

Ubuntu, Collaboration, and Peer Support

Preference for learning methods in the Ghanaian sociocultural context was summed up by a PA student as follows: “For a Ghanaian, learning should be one of interaction as we do not do work alone” (Gunawardena et al, 2016). PA students pointed out that Ghanaian students form study groups on their own, and work collaboratively, as we observed during our visit to GU. “In African cultures, working together is prominent and learning is inherently a collective social process whereby a student feels the need to interact with fellow students and teachers. This deeply social view of education is embodied in Ubuntu” (Makoe & Shandu-Phetla, 2019, p. 131), which means “an individual person owes his or her existence to the existence of others” (p. 130). Makoe and Shandu-Phetla explain that Ubuntu is in direct contrast to individualism, which is espoused in most Western learning contexts. “Despite the colonial influence on the African way of life, African cultures discourage the view that the individual takes precedence over the community” (p. 132). Therefore, interaction and collaboration are central to the African way of learning.

PA students offered advice on how to group students for small group activities, recommending that we group students regionally because when they experienced bad wireless connections they could go to each other’s villages to get support and learn together. The Ghanaian lead supported this request for regional grouping. This preference for grouping may have also been influenced by regional tribal affiliations. In the Ghanaian sociocultural context, we learned the value of collaborative learning, and learning within a learning community supported by co-mentoring.

Outside of formal facilitator or mentor formed peer groups, informal peer groups or study buddies are an excellent means of support for the online learner. Utilizing peer groups that are organically formed is an ideal way of providing much needed learner support. During online discussions, we found that women would be more reticent to participate, and therefore would need more guidance and support to feel comfortable. Peer mentoring and tutoring as discussed in the Sri Lankan project may be one way to address this need for support. Makoe and Shandu-Phetla share their experiences with a project where they encouraged students to work together in WhatsApp, a mobile-based social network, to improve their English vocabulary. In low bandwidth areas, WhatsApp is more readily accessible than an LMS, and is an ideal medium for learner support considering its affordances that enable sharing of text, audio, images, video, the ease of creating small group discussions, and its popularity and access among students. While mobile technology can extend the notion of learning beyond the traditional classroom, designers need to carefully negotiate the potential of mobile affordances with expectations for traditional teacher directed learning environments.

Power, Authority, Status

We observed that hierarchy and power distance played a role in the educational transaction, especially, the relationship between PA students and the Ghanaian Lead. During our needs assessment, students stated that they respected age and teachers and found it difficult to question authority. However, when the authority figure of the teacher was removed in a focus group interview with 22 PA students from different regions in Ghana, the students opened up to the North American partners about their concerns related to the project and offered to work as a team to co-design the online case studies. "We see 40-50 patients in an 8 hour day. We have to be prepared for anything at all times. In one day we can see a woman with pregnancy difficulties, to people with malaria” (Gunawardena et al, 2016). Ghanaian students felt that online interaction may be preferable because it could equalise status differences present in face-to-face interaction.

While students may prefer the online environment, instructors who like to maintain power and authority have a difficult transition. In this project, it was very difficult for the instructor to move to a facilitator role as he felt that some of his authority was being eroded in online discussion spaces where he had no control. Instead of facilitating online discussions, he maintained authority by calling students on their mobile phones to explain questions they had asked in online discussions. In this instance, mobile technology helped to solidify the authority of the teacher, maintain the status quo, yet personalise the communication for an individual student in an oral culture that relies on face-to-face communication. This example also reflects the Ghanaian Lead’s discomfort in facilitating online discussions. It was difficult for him to grasp how technology is changing the role of the teacher from a disseminator of information to a learning facilitator. Therefore, the North American team took it upon themselves to facilitate discussions online often on unfamiliar topics so that the Ghanaian students felt supported in an online environment. To help learners to negotiate power dynamics and develop an inclusive learning environment we need to support instructors to transition to the role of a facilitator and mentor, valuing and utilizing students’ prior experiences and skills. Faculty development programs addressing instructor mindset, facilitating, tutoring, mentoring and course design are essential if online learning is to address diverse learner needs.

From an instructional design perspective, we felt we were not giving students what they needed to succeed. As a Subject Matter Expert, the Ghanaian Lead did not make the effort to guide the learning design. We created the modules in Moodle based on the content he provided in a Dropbox, but we were never shown how the modules might connect with the clinical work students would be doing for the course. If we had had the chance and time to work with the PA students who indicated their willingness to be co-designers, we could have designed a more relevant and culturally inclusive learning experience.

Technology Affordances and Interface

Technology connects us but is not culturally neutral. While many perceive the Internet as a value neutral tool, we must be we aware of the underlying tendency of its users to colonise and import dominant paradigms into contexts that are either unfriendly to those paradigms or that can be harmed by those solutions (Carr-Chellman, 2005). While developing the Moodle interface for the PA program, our Western biases unconsciously crept in, and we learned through trial and error, that the interface must be aligned to reflect the Ghanaian cultural context (Gunawardena et al 2016). For example, when we developed the first gynecology course, we had initially put a photograph of an intensive care unit for babies in the US in the course title theme block of Moodle as seen in the screenshot in Figure 1. However, this photograph reflected a Western paradigm, and was alien to the Ghanaian cultural context. Our design partners in Ghana wanted the photograph removed and replaced with a photograph that represented the Ghanaian context, a Ghanaian woman and her baby as seen in the screenshot in Figure 2. Images and photographs must relate to the cultural context.

Figure 1. Initial Interface Design of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Course.

Source: Gunawardena, Frechette, & Layne (2019). Used with permission.

Figure 2. Revised Interface Design of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Course.

Source: Gunawardena, Frechette, & Layne (2019). Used with permission.

In online designs, interpretation of visual meanings may reflect the distance between the cultural values of the viewer and those of the designer as we found in a study of interpretations of icons and images conducted in four countries: Turkey, Spain, Sri Lanka, and the US (Knight, Gunawardena, Barbera & Aydin, 2014). Several factors influenced the interpretation of icons in each cultural context: age, native language and associated ways of thinking, religious beliefs, gender and appropriate behavior, frequency of Internet use, and the graphic form of the image, whether a photograph or line drawing. Our research suggested that: (1) photographs may be difficult to interpret across cultural contexts because they are information dense and may contain details which carry distinct cultural meanings; (2) icons and images that are representational and require literal interpretations, such as the email icon, planner icon, and calendar icon, may be most reliable for use in multicultural online environments; and (3) icons that are conceptually focused and contain little detail, such as the accessibility icon and calendar icon used in the study, were less likely to elicit their intended meaning as concepts of accessibility and calendar vary across cultures, and may be visualised differently (Knight et al, 2014).

In Ghana, we wanted to build a blended learning environment utilizing online and mobile technologies from the ground up so that the learning experiences and content would reflect the culture that created it. We realised that such an effort requires an enormous time commitment which the volunteer North American team found challenging. While we wanted to move toward to a more negotiated culture of cooperation, nuances of unfamiliar cultures, alternative expectations, and new layers of institutional hurdles, impacted our efforts to develop the best possible learning solution. While this volunteer student project reached new heights by demonstrating that online education projects can be designed and developed at a distance for an unfamiliar sociocultural context, we faced many challenges because we had to work remotely. We recommend that future international partners spend time in the field learning the hidden culture of individuals, groups, organizations, and communities that will implement the project.

In this section, I provide guidance for culturally inclusive online learning design for capacity development projects, based on my experiences with the two projects discussed, and many other design experiences in the US and overseas. I do so by sharing a design framework my colleagues and I have developed over the past two decades to guide the design of culturally inclusive online learning through the development of wisdom communities that engage in solving complex problems. This framework, Online Wisdom Communities, or WisCom, is described in detail in our book which represents the most complete presentation of the framework to date and provides a range of tools, techniques, and strategies to cultivate wisdom communities (Gunawardena, Frechette & Layne, 2019). I discuss this design framework here, in relation to the lessons learned from the two international projects in Sri Lanka and Ghana.

In addition to universal design principles (Barajas & Higbee, 2003) we have incorporated into the WisCom framework, we share the following assumptions about culturally inclusive design:

The WisCom design framework presented next incorporates these assumptions, and our collective experiences designing and teaching online in diverse contexts.

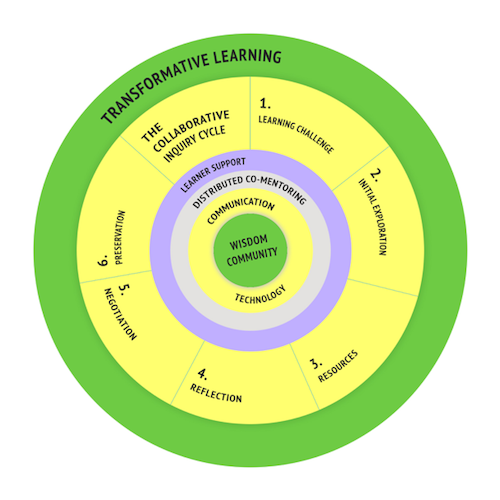

The crux of the WisCom framework lies in the attainment of transformative learning through collaboration, reflection, and exploration in a wisdom community. Situated in sociocultural and socioconstructivist theories, the framework incorporates several core elements: wisdom, community, communication, technology, co-mentoring, learner support, collaborative problem solving, and transformative learning. Figure 3 illustrates the WisCom framework which is explained in this paper in relation to the two international projects discussed earlier.

Figure 3. WisCom Framework.

Source: Created by Casey Frechette for Gunawardena, Frechette, & Layne (2019).

Wisdom

Every culture defines wisdom differently but all highlight wise people’s practical knowledge and sound judgment. In Africa, wisdom is an important epistemological tenet, and proverbs reinforce the role of wisdom in African indigenous epistemology, for example, “you cannot have an old head on young shoulders” signifying that a young person cannot possess the wisdom and experience of an older person (Ntseane, 2007). In the Sri Lankan sociocultural context, predominantly influenced by Buddhism, wisdom is the goal one must attain through education. The Buddha’s teachings help one to realise that innate, perfect, and ultimate wisdom. With wisdom, one can solve problems and turn suffering into happiness (Rahula, 2015). These and other cultural perspectives on wisdom have led us to consider wisdom as the goal and core value of an online learning community. We view wisdom as a personal quality that can be cultivated to enhance a community; a wisdom community honors the gifts its members bring and promotes imparting those gifts to others. Wisdom as a value often appears alongside another core goal in WisCom: transformative learning. Wise people engender transformative learning in themselves and others, while transformative learning increases wisdom (Gunawardena, Frechette & Layne, 2019).

Community

Community is at the heart of the WisCom framework as illustrated in Figure 3. Wisdom is the value the online community seeks to develop. Learning within WisCom is community centered as learners navigate the process of learning, collaborate, and become collectively wise. The community provides opportunities for learners to interact, receive feedback from peers, mentors and facilitators, learn, and grow together. The goal of WisCom is to create a wise community that shares a common mission, engages in reflection and dialogue, affirms mutual trust, respect, and commitment, empowers its members, and cares for the common good. Ubuntu, the central concept of community and collaboration in the African sociocultural context aligns well with the central concept of community in the WisCom framework. The two international projects demonstrated that interaction and community are central to the learning process and culturally inclusive designs must create a sense of belonging to a learning community. Totally self-directed learning designs that do not accommodate interaction and community, are not culturally inclusive.

Communication

Communication is the lifeblood of an online wisdom community. Through effective communication, a community forms an identity, builds trust, enhances social presence and strengthens its bonds. Online communication can be challenging as it is often devoid of contextual information. In both the Sri Lankan and Ghanaian cultures it is important to pay attention to the context of a message as indirect communication often needs to be understood within the context and relationships. One challenge to communication will be the use of English as an additional language. Providing communication protocols that guide communicating online as well as allowing for translanguaging when participants are fluent in two or more languages can alleviate some of the communication anxiety experienced by users of an additional language.

Technology

Technology mediates all experiences in an online wisdom community. Because cultural biases often shape the design of digital tools, carefully reflecting on how to implement technology tools to find, filter, record and dialogue with one another will result in more inclusive learning experiences. Orientation to the use of online technology for both participants and instructors/facilitators is vital to develop a level of comfort with the technology. The WisCom framework provides guidance on how to use available technologies in a given learning context, along with how to select tools when the opportunity to do so arises.

Distributed Co-Mentoring

The Sri Lankan project highlighted the value of e-mentoring and mentoring relationships across cultures to support online learning. In WisCom we conceptualise mentoring as “co-mentoring” (Bona, Rinehart & Volbrecht, 1995). Co-mentors are collaborators who construct knowledge together and by supporting one another co-mentoring leads to the formation and sustenance of a culturally inclusive learning community. Mentoring relationships traditionally involve an expert who imparts knowledge and delivers support to a novice. Our emphasis on co-mentoring challenges the utility of these roles. We believe that the more distributed, equitable nature of the online environment underscores collaborative learning and relationship networks. The Ghana project showed how practicing PAs will be ideal co-mentors with their reservoir of experience. Setting up conducive co-mentoring relationships is important. Co-mentoring can involve peers, facilitators, and community members who may be situated locally, nationally, or internationally.

Learner Support

Since each learner experiences a unique set of circumstances, some of which may impede progress toward learning goals, learner support systems should provide the scaffolding and encouragement needed to overcome challenges. In the Ghanaian context, PAs pointed out the need to form support groups regionally so they could support each other when wireless connections were weak. An effective learner support system in WisCom reflects the diversity of learners' experiences, including differences in age, gender, cultural background, education, language, socioeconomic status, family and employment commitments, goals, objectives, needs, desires, and access to technology.

As we design learner support, it is important to remember that each learner has unique needs and learning preferences. We need to delicately balance activities that give opportunities to learn in preferred ways and activities that challenge the learner to learn in new or less preferred ways.

Problem Solving and the Collaborative Inquiry Cycle (CIC)

The CIC is a process for designing an IBL experience in which learners work alone and together to explore an ill-defined problem or scenario. Based on an initial instructional prompt, such as the three problem scenarios in the Sri Lankan context, (garbage, traffic, and street children), learners research, write, discuss, reflect, synthesise, evaluate, and summarise. When the cycle concludes, the community captures the insights and knowledge constructed. The Ghanaian PAs pointed out the appropriateness of the case-based reasoning format for their learning context and offered to be co-designers of the CIC, incorporating authentic problems from their practice. The CIC shifts learners from teacher directed learning environments, where the sage on the stage imparts one point of view, to more culturally inclusive problem solving where all participants have a voice.

The CIC incorporates each building block of online wisdom communities — technology, communication, wisdom, and learner support — to form an interactive, experiential process. The power of the cycle is the way it helps learners build both domain-specific expertise and generalizable 21st-century skills, including critical thinking, patience and reflection, the ability to recognise patterns and trends, collaboration, and the flexibility to find cross-cultural, interdisciplinary solutions (Lombardi, 2007).

Transformative Learning

The most important outcome of a wisdom community is transformative learning, which includes three interlocking ingredients: intention, knowledge, and action (Rowley, 2006). Intention signals a shift in attitudes toward an idea, person or group. Knowledge involves the acquisition of information. Action entails new behaviors and skillsets. These elements emphasise the holistic nature of transformative learning, which requires concurrent changes in attitude, cognition, and behavior. Transformative learning differs from typical learning outcomes in both its expansiveness and longevity; the change must lead to perspective transformation (Gunawardena, Frechette & Layne, 2019). In the Sri Lankan context, transformative learning supports the Buddhist perspective on education which aims at personality transformation into the highest form of humanity through ethical, intellectual and spiritual perfection (Rahula, 2015). Transformative learning amounts to personal growth; wisdom communities create the conditions in which it is likely to occur by promoting insight, flexibility, and humility (Gunawardena et al, 2006). However, to grow, learners must gain new perspectives of themselves and their worlds. Often, this means challenging a previously, perhaps deeply, held belief. We see the WisCom framework, with its focus on real-world problem solving through inclusive communication, as one approach to support transformative learning.

Cultural Biases in WisCom

WisCom, like any learning design framework is the product of various cultural forces. Although we believe WisCom is particularly well-suited for multicultural contexts, we also acknowledge its limitations and biases. Most notably, WisCom puts great emphasis on the role of the instructor as a facilitative one, and this may be unfamiliar or unproductive to students who expect the teacher to be an authority figure who directs their learning (Jin & Cortazzi, 1998).

WisCom focuses on inquiry-based learning formats, such as case based reasoning and problem solving in ill-structured domains, which require active participation from learners. This may inconvenience learners who are more used to a teacher directed format or expect direct guidance like the Sri Lankan participants did in the e-mentoring experience.

Similarly, WisCom’s focus on group-based collaborative learning may put some learners who prefer to work alone at a disadvantage. Although individual contributions are counted and valued, WisCom’s emphasis on group dynamics may prove counterintuitive for students whose learning has been rooted in individualistic cultural values. However, we also see value in pushing students to the edge of their comfort zones and see opportunities in the presence of unfamiliar ways of learning that WisCom likely presents for at least some students. This is where mentoring and facilitating can play a key role in supporting these students (Frechette, Layne & Gunawardena, 2014).

Digitalization brings new challenges and opportunities. Harnessing these opportunities for appropriate change will make learning more accessible and inclusive. This paper explored the concept of cultural inclusivity in online learning design in two international capacity development projects in Sri Lanka and Ghana. It addressed the importance of establishing partnerships to develop and maximise the capacity that already exists in a given context, and the vital role of a needs assessment. Cultural factors that impacted online design in the two projects were discussed in relation to developing a learning community, negotiating identity, power, and authority, supporting collaboration, engaging in authentic inquiry-based learning, navigating interactions in an additional language, and developing co-mentoring relationships to support learning online.

To provide guidance for culturally inclusive design, I introduced our WisCom, (Wisdom Communities) design framework, well-suited for culturally-diverse learning cohorts. By emphasizing divergent thinking, collaboration and consensus building in knowledge construction, and the exploration of multiple solutions to complex, authentic problems, WisCom maximises opportunities for students’ diverse backgrounds and experiences to be valued and appreciated.

Cross-cultural understanding is a learning journey traversing many contexts. My learning became both a personal and a collaborative journey with my students, local and international partners through a complex set of cultural contexts. The journeys transformed us and helped us to reflect on who we are and how we interact with others. This is my story and my perspective. My own biases and mental frameworks have influenced the stories I have shared. We need to explore other stories from alternative perspectives of those who have implemented online learning in capacity building projects in international contexts.

Acknowledgement

This paper draws extensively from an earlier publication: Gunawardena, C. N., Frechette, C., & Layne, L. (2019). Culturally inclusive instructional design: A framework and guide for building online wisdom communities. New York: Routledge.

Alexander, B., Ashford-Rowe, K., Barajas-Murphy, N., Dobbin, G., Knott, J., McCormack, M., Pomerantz, J., Seilhamer, R., & Weber, N. (2019). EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: 2019 Higher Education Edition. Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE.

Avgerou, C. (2010). Discourses on ICT and development. Information Technologies & International Development, 6(3), 1-18.

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Barajas, H. L., & Higbee, J. L. (2003). Where do we go from here? Universal design as a model for multicultural education. In J. L. Higbee (Ed.), Curriculum transformation and disability: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 285–290). Minneapolis, MN: Center for Research on Developmental Education and Urban Literacy, General College, University of Minnesota.

Biesenbach-Lucas, S. (2003). Asynchronous discussion groups in teacher training classes: Perceptions of native and non-native students. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(3), 24-46. Retrieved from http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/jaln_main

Bona, M. J., Rinehart, J., & Volbrecht, R. (1995). Show me how to do like you: Co-mentoring as feminist pedagogy. Feminist Teacher, 9(3), 116-124. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40545722

Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2005). Introduction. In A. A. Carr-Chellman (Ed.), Global perspectives on e-learning: Rhetoric and reality (pp. 1-16). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chen, G. M. (2000). Global communication via Internet: An educational application. In G. M. Chen & W. J. Starosta (Eds.), Communication and global society (pp. 143-157). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

Ess, C. (2009). When the solution becomes the problem: Cultures and individuals as obstacles to online learning. In R. Goodfellow & M. N. Lamy (Eds.), Learning cultures in online education (pp. 15-29). London, UK: Continuum.

Frechette, C., Layne, L., & Gunawardena, C. N. (2014). Accounting for culture in instructional design. In I. Jung & C. N. Gunawardena (Eds.), Culture and online learning: Global perspectives and research. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Goodfellow, R., & Hewling, A. (2005). Reconceptualising culture in virtual learning environments: From an "essentialist" to a "negotiated" perspective. E-Learning, 2(4), 355-367. doi:10.2304/elea.2005.2.4.355

Goodfellow, R., & Lamy, M. N. (Eds.). (2009). Learning cultures in online education. London, UK: Continuum.

Gunawardena, C. N. (2004). The challenge of designing inquiry-based online learning environments: Theory into practice. In T. Duffy & J. Kirkley (Eds.), Learner centered theory and practice in distance education: Cases from higher education (pp. 143-158). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Gunawardena, C., Faustino, G., Keller, P., Garcia, F., Barrett, K., Skinner, J., Gibrail, R., Jayatilleke, B., Kumarasinha, M., Kulasekara, G., & Fernando, S. (2013). E-mentors facilitating social construction of knowledge in online case-based reasoning. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Mentoring Conference (pp. 60-68). Albuquerque, New Mexico: The University of New Mexico, The Mentoring Institute.

Gunawardena, C. N., Frechette, C., & Layne, L. (2019). Culturally inclusive instructional design: A framework and guide for building online wisdom communities. New York: Routledge. Website for the book: https://www.colectivo.io/

Gunawardena, C.N., Keller, P.S., Garcia, F., Faustino, G.L., Barrett, K., Skinner, J. K., Gibrail, R. P. S., Jayatilleke, B. G., Kumarasinha, M.C.B., Kulasekara, G.U., & Fernando, S. (2011). Transformative education through technology: Facilitating social construction of knowledge online through cross-cultural e-mentoring. In V. Edirisinghe (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on the Social Sciences and the Humanities (1), pp. 114-118. Peradeniya, Sri Lanka: The faculty of Arts, University of Peradeniya.

Gunawardena, C. N., Lowe, C. A., & Anderson, T. (1997). Analysis of a global online debate and the development of an interaction analysis model for examining social construction of knowledge in computer conferencing. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 17(4), 395-429.

Gunawardena, C. N., Ortegano-Layne, L., Carabajal, K., Frechette, C., Lindemann, K., & Jennings, B. (2006). New model, new strategies: Instructional design for building online wisdom communities. Distance Education, 27(2), 217–232.

Gunawardena, C. N., Palalas, A., Berezin, N., Legere, C., Kramer, G., & Amo-Kwao, G. (2016). Negotiating cultural spaces in an international mobile and blended learning project. In L. E. Dyson, W. Ng, & J. Fergusson (Eds.), Mobile Learning Futures – Sustaining Quality Research and Practice in Mobile Learning. Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, mLearn 2016. Sydney, Australia: The University of Technology.

Gunawardena, C.N., Skinner, J.K., Richmond, C., Linder-Van Berschot, J., LaPointe, D., Barrett, K., & Padmaperuma, G. (2008, March). Cross-cultural e-mentoring to develop problem-solving online learning communities. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York, NY.

Gunawardena, C. N., & Zittle, F. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer mediated conferencing environment. The American Journal of Distance Education, 11(3), 8-25.

Hall, E. T. (1959). The silent language. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Jayatilleke, B. G., Kulasekera, G. U., Kumarasinha, M. C. B., & Gunawardena, C. N. (2012). Cross-cultural e-mentor roles in facilitating inquiry-based online learning. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of Asian Association of Open Universities (pp. 60-68). Chiba, Japan.

Jayatilleke, B. G., Kulasekara, G. U., Kumarasinha, M. B., & Gunawardena, C. N. (2017). Implementing the first cross-border professional development online course through international e-mentoring: Reflections and perspectives. Open Praxis, 9(1), pp. 31-44.

Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (1998). Dimensions of dialogue: Large classes in China. International Journal of Educational Research, 29(8), 739-761.

Jonassen, D. H., & Kim, B. (2010). Arguing to learn and learning to argue: Design justifications and guidelines. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(4), 439-457.

Knight, E., Gunawardena, C. N., Barberà, E., & Aydin, C. H. (2014). International interpretations of icons and images used in North American academic websites. In I. Jung & C. N. Gunawardena, (Eds.), Culture and online learning: Global perspectives and research (pp. 149-160). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Lambert, S. R. (2020). Do MOOCs contribute to student equity and social inclusion? A systematic review 2014-18. Computers & Education, 145, 103693. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103693

LaPointe, D., Richmond, C., VanBerschot, J. A., Gunawardena, L., Barrett, K., Cardiff, M., & Skinner, J. (2008). E-mentoring strategies for cross-cultural learning and community building. Proceedings of the 2008 Mentoring Conference: Fostering a Mentoring Culture in the 21st Century (pp. 107-114). Albuquerque, NM: The University of New Mexico, Mentoring Institute.

Liyanage, L., Pasqual, A., Wright, C. (2010, May). Lessons learned in managing ICT systems for online-learning. Paper presented at the MIT LINC Conference. Cambridge, MA: MIT. Retrieved from https://linc.mit.edu/linc2010/proceedings/session9Liyanage.pdf

Lombardi, M.M. (2007). Authentic learning for the 21st century: An overview. Educause learning initiative, ELI Paper 1, pp. 1–12.

Lopez-Islas, J. R. (2001, December). Collaborative learning at Monterrey Tech-Virtual University. Paper presented at the Symposium on Web-based Learning Environments to Support Learning at a Distance: Design and Evaluation. Asilomar, Pacific Grove, California.

Ludwig-Hardman, S., & Dunlap, J. C. (2003). Learner support services for online students: Scaffolding for success. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 4(1). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v4i1.131