VOL. 6, No. 1

Abstract: As long ago as 1992, Greville Rumble was writing about the “competitive vulnerabilities” of single-mode distance teaching institutions [universities]. In the intervening years the challenges he described have only intensified, especially so as advancing information and communication technologies have enabled increasing numbers of campus-based tertiary institutions to enter distance learning, usually targeting the part-time adult learner market that was formerly the preserve of single-mode distance learning providers.

There are also wider and larger pressures at play. Disruptive digital technologies, globalisation of education, constrained government funding, shifting student expectations, and changes in demand for future skills, are all driving the need both to re-examine fundamental aspects of the ODFL (open, distance and flexible learning) model (as indeed they are for tertiary education more generally), and to re-consider the core ODFL principle of “learner-centricity” and what it might mean within this changing context.

The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand has recently undertaken a major programme of digital and organisational transformation to meet the changing needs of its distinctive learner constituency, and to enhance the organisation’s flexibility in responding to changing external factors. This institutional reengineering that disaggregates functions and unbundles processes and services, holds potential for both improved performance and enhanced partnering opportunities within a network of provision.

Keywords: transformation, change, open and flexible learning, technical and vocational training.

In today’s changing tertiary education landscape, the message for single-mode ODFL institutions seems clear: they cannot rest on the (significant) achievements of the past but must continue to innovate by themselves, leveraging the affordances of advancing technology in order to enhance the learner experience and outcomes, to increase productivity, and to drive responsiveness (Garrett et al, 2018).

Drawing lessons from the challenges faced by single-mode ODFL providers in Canada, Bates puts it thus:

No unique/non-conventional institution can survive without:

- being clear about what makes it unique, and continuously identifying its uniqueness in changing circumstances;

- having a clear strategy and plans to meet that unique mandate;

- being nimble enough to adapt rapidly to changing external factors, without losing its unique advantages (Bates, 2015).

Bates’ formulation also answers the immediate and obvious question of why, if a multitude of pressures and forces might be held to suggest otherwise, should single-mode ODFL organisations be preserved beyond their own desire for institutional self-preservation? As Bates suggests, such providers will earn their ongoing place within their particular system context if they continue to demonstrate their unique contribution and relevance; and to do this, more than ever they will need a high degree of flexibility to adapt and respond to continuous change in their external environment.

At a general level, when managed well, ODFL provides wider access to cost-efficient and educationally effective flexible learning for people who cannot or (now more commonly in many countries) who do not wish to attend campus-based study. Single-mode ODFL institutions establish a fully integrated distance-teaching system with subsystems for developing course materials and providing student support and instruction. When optimised, the single-mode ODFL model breaks the ‘Iron Triangle’ of Cost, Quality & Access, and cost-efficiencies increase with scale (Daniels, 1998, 2010, 2018; Keegan, 1994).

There are multiple variables that impact on whether ODFL provision is optimized, whatever its institutional setting. These range across jurisdictional issues, policies and history; pedagogy, mission, delivery mode (print vs online or combinations thereof), management practice, academic culture, technology and multi-media investment, student base and size and so on.

The following describes the experience of one single-mode ODFL institution, Open Polytechnic of New Zealand (OPNZ), as it embarked on and continues to implement a major transformation programme designed to maximise its contribution to the future New Zealand tertiary education system within the broader context described above.

This process is additionally taking place against a background of increasingly intense financial pressures on New Zealand’s Institutes of Technology & Polytechnics (ITP) sector, which in 2018 saw the Government initiate a large-scale sector-wide review (OPNZ is one of a small number of ITPs that continues to perform strongly).

At the core of Open Polytechnic's transformation strategy is a focus on making the best use of emerging digital technologies both to service the changing needs of its distinctive learner constituency, and to increase the organisation’s flexibility in responding to changing external factors, whether of demand, funding, specific government priorities or industry need. This broad programme has two main parts, either of which on their own could justly have been described as “transformational.”

The first part involved the monumental task of converting the organisation’s entire legacy portfolio of print-based qualifications to online delivery on the Polytechnic’s own custom-built digital learning platform (now complete). The second and ongoing phase, called the Transformation Change Programme (TCP), involves an equally significant and fundamental re-design of the organisation’s teaching, learning, delivery and assessment model and practice, along with parallel supporting work streams focusing on the organisational culture and working environment.

In overview, the Open Polytechnic of New Zealand is its country’s only specialist distance provider of higher education. Established over 70 years ago to provide post-war technical education by correspondence, today it is New Zealand’s preeminent provider of vocational education and training in the ODFL modality.

Open Polytechnic offers over 100 programmes leading to recognised and approved qualifications from certificate to bachelor degree level. Annually 30,000 learners enrol with the Polytechnic (a significant level of penetration in a national population of 4.8 million). They are mostly employed and studying to upskill, generally aged over 25 years (although a sizeable cohort – 21% - are younger) and juggling many life commitments. Their distribution mirrors the New Zealand population and demographics, with the majority residing in the largest urban centres where a full set of campus-based study options is available.

In other words, Open Polytechnic’s mainly working learners proactively choose the organisation above traditional face-to-face study because the flexibility it offers enables them to fit learning into their time-poor lifestyles.

A key strategic driver for Open Polytechnic is the recognition that the need for flexibility in learning will only increase for its core group of working learners and their employers, as well as for the organisation itself in terms of its agility in an environment of constant change.

The beginning of the current transformation programme traces back to 2014 when OPNZ, which had been an early adopter and promoter of Moodle in New Zealand, resolved to invest in building its own digital learning platform; this becoming key to the Polytechnic’s future strategy. The platform was specifically designed to support learner-centric online learning, both as a full distance learning experience and as the online component of blended delivery for partner organisations (the platform is also being marketed as a commercial product).

Owning and controlling its own digital technology and designing a platform with learner‑as‑user first principles, aimed to (and has) strategically repositioned OPNZ as a fully digital ODFL organisation. Fairly quickly after the initial deployment (and validation) of the platform, the decision was made to accelerate digital conversion of OPNZ’s entire, mainly print-based portfolio of content and programmes. Embarking on such a process is regularly cited as one of the major strategic and financial challenges facing established single-mode ODFL organisations (Teixeira, Bates, & Mota, 2019). In OPNZ’s case the resource and financial pressures were intense, but the conversion process is now complete.

Open Polytechnic is now moving into the next phase of the Transformation programme, the objectives of which include breaking with the trimesters, cohort-based format currently used for diploma and degree programmes and moving to a fully flexible enrol and assessment-on-demand model.

To this end, a key element of the Transformation Change Programme is the enhancement of the component parts of the ODFL disaggregated value chain. A significant feature of this enhancement has been a form-follows-function approach to reorganising OPNZ’s business units, including Faculty, and repurposing the work of academic staff members. This has established the design and commitment to unbundle the academic staff role.

The over-arching framework for the TCP is OPNZ’s 2016-2020 Strategic Plan, which sets out four key goals to be achieved:

In addition to the framework provided by strategic plan, OPNZ’s governing body, it’s Council, mandated a vision for the organisation’s future. This is a vision that reflects international best practice in ODFL and the Polytechnic’s values of: True, Fast, Bold and Best.

Open Polytechnic’s future state vision is described by identifying 4 essential components of the learning experience. These are:

The kind of change that results in the transformation of an organisation is deep and pervasive; it is intentional change that will occur over time and have an effect on the culture of the institution (Eckel and Kezar, 2003). OPNZ’s transformational change aligns with understood definitions of this type of organisational change. The Polytechnic does expect there to be change to its institutional culture (with a specific work stream to further this end), and that deep and permanent change will be achieved as the programme progresses and matures.

The drivers for transforming OPNZ are those described earlier in this article. In responding to these predominant influences, the essence of the change programme lies in the Polytechnic’s ability to offer learners a future-focused, personalised and highly flexible way of engaging with vocational tertiary education and training. The benefits of the change will be experienced by OPNZ’s own learners, and through potential cross-sector collaborations, learners who are enrolled with other tertiary education organisations, both nationally and internationally.

Much of the change being driven by the TCP is still either under implementation or is at the early stages of being institutionalised, while some of the elements of the TCP are planned but yet to be implemented. So, OPNZ is at a relatively immature stage in this phase of its change journey. Just the same, there are already a significant number of valuable points of learning arising out of this programme. These include: the support and commitment of governance; identifying, registering and managing risk; accepting the messiness of change and navigating the clean-up; securing expertise, advice and input to the change programme; and what the change programme means for organisational leadership and the leadership team.

In what is the most significant change initiative undertaken in the history of the Polytechnic, implementation of the Transformation Change Programme (TCP) was preceded by a rigorous design activity.

Cross-functional teams of staff, working in facilitated groups, contributed to three design work streams: learning support; assessment; and all-of-organisation systems and processes. The work streams considered new ways of engaging with learners and working across the organisation, with the aim of achieving a more flexible and future-proof organisation better able to respond to the current and future needs of learners and industry.

At key stages in the design process input was sourced from a Learner Reference Group (comprising current OPNZ learners), an assembled panel of international ODFL experts, and site unions. Consultation was also undertaken with key external stakeholders, including relevant New Zealand Government agencies and regulatory entities.

The output from the work stream groups, along with the advice received from the reference and consultation processes was consolidated into a single blueprint document. The blueprint is a key reference document in the subsequent implementation of transformational change in the organisation. It guides thinking and decision making and informs the actions and initiatives that result in the changes being sought.

The output from the design phase of the change programme, the blueprint, has been formally adopted as OPNZ’s future state ODFL operating model. It is this model that has informed subsequent changes to OPNZ’s organisation structure. This is a key feature, and perceived strength, of the approach taken by the Polytechnic to transformational change. The resulting organisation structure, implementation of which commenced in the second quarter of 2018, creates teams of specialist staff identifiable by their function, where that function is clearly linked to the ODFL Operating Model.

The intent of making changes to the Polytechnic’s organisation structure has been to create teams of specialist staff, and adjuncts, where the function of each is clearly identifiable to the extent that they work together in a seamless whole to give effect to the described ODFL Operating Model.

An example of form based on function is the establishment of a new Assessment Centre. The ODFL operating model describes the future state of educational delivery in which learners participate in summative assessment, and have access to recognition of prior learning services, independently of their engagement in formal learning activities. This is a critical feature of Open Polytechnic’s future operating model which provides for the level of flexibility and learner-driven decision making that characterises the ODFL online, digital learning experience.

Uncoupling access to assessment from learning achieves the desired state of flexibility and learner-driven choice that is anticipated in the future state ODFL Operating Model and speaks to the expectations of the future state vision described above. The organisation and its stakeholders can find assurance of the achievability of this through the realisation that the structure of the organisation, and the allocation of resources to that structure, provides the appropriate organisational form to deliver on the described function.

As the preceding example of the establishment of the Assessment Centre demonstrates, to achieve the extent of flexibility in delivery, learner-driven choice, and personalised learning and support that the ODFL Operating Model requires, it is vital that each of the key components of the value chain be disaggregated in a way that they can be offered as a standalone, independent service or feature to the learner. This has necessarily meant that as Open Polytechnic has embarked on its journey of transformational change that the role of Faculty – as an organisational entity, and the work of the academic staff members in the Faculty, be subjected to close scrutiny. The consequence of this scrutiny and the organisation’s drive to implement change that ensures the achievement of the vision of the future state ODFL Operating Model, has been the development of a model that explains how unbundling of Faculty has occurred.

In this section of the article we set out the how the polytechnic has modelled its unbundling of Faculty and the alignment of this unbundling with the organisation’s future state structure, an organisational structure that has been established and staffed during 2018.

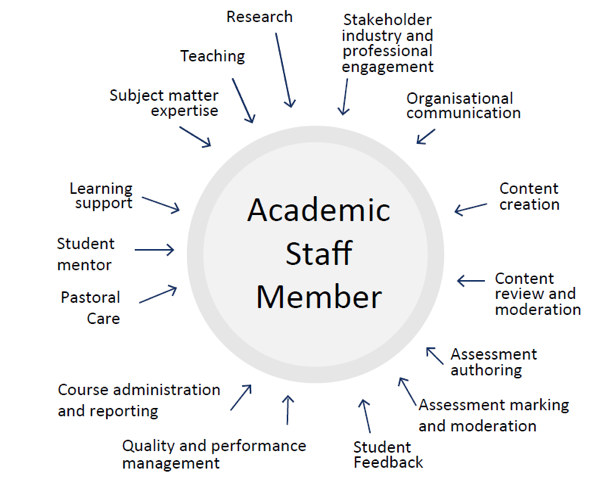

The unbundling model is presented as three graphically depictions. The first of these describes a Faculty-centric view of the role of the academic staff member (Figure 1). This is followed by a depiction of how the TCP worked to group the traditional activities of Faculty into logical activity groupings. In the third and final graphic, the activity groupings are associated with organisational structure, the structure that the Open Polytechnic has in place now.

Figure 1: A Faculty-centric view of the role

of the academic staff member.

In this view of the academic staff member’s role, all aspects of the value chain that support the delivery of education and learning interact in some way with the work that the academic staff member does. Where an ODFL organisation, such as OPNZ, harnesses a value chain where specialist parts of the delivery ‘system’ are separately organised, i.e. a “disaggregated” value chain, there is an obvious misalignment between the way the organisation goes about delivering education and the holistic view of the role of the academic staff member and Faculty.

A significant impact of the TCP has been to re-envisage how the holistically arranged, traditional functions of Faculty are to be aligned with a learning and teaching model that will realise the expectations of the future state ODFL Operating Model.

To an extent, the disaggregated components of the ODFL value chain have already informed unbundling of the role of the academic staff member prior to the adoption of the TCP. Two examples of this are: content creation, where learner resources have been designed, and written independently of Faculty; and assessment marking, where historically adjunct faculty have supplemented the job of marking learners’ assessment. However, the TCP has resulted in the adoption of a whole-of-organisation approach to a change in the structure of the organisation that more closely aligns organisational activity with the learning and teaching model.

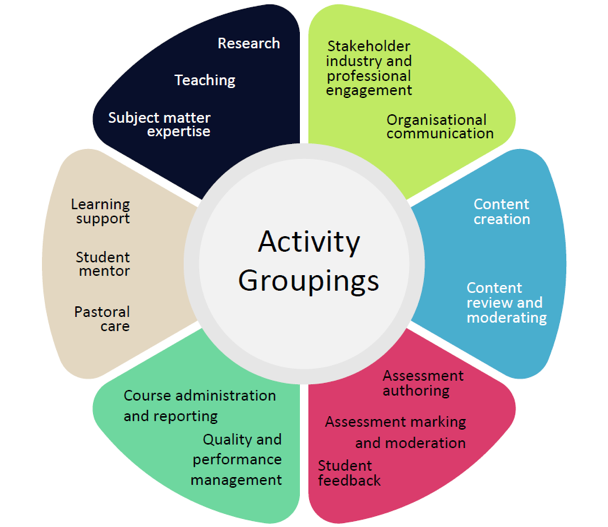

The activities that are seen in the graphical depiction of the academic staff member’s role (as above) can be logically grouped into areas of activity that align with the learning and teaching model and the learner’s journey. This following Figure 2 shows how that grouping has been conceptualised.

Figure 2: Logically arranged activity groupings.

By comparing the activities shown in the first of the graphs, that is those associated with a holistic view of Faculty and the academic staff member’s role, with the groupings shown in this second graph (as above), it is apparent that these subsequent groups of activities are quite simple logical assemblies of like activities all of which have been previously identifiable as those that may have been undertaken by academic staff members in part, or in whole.

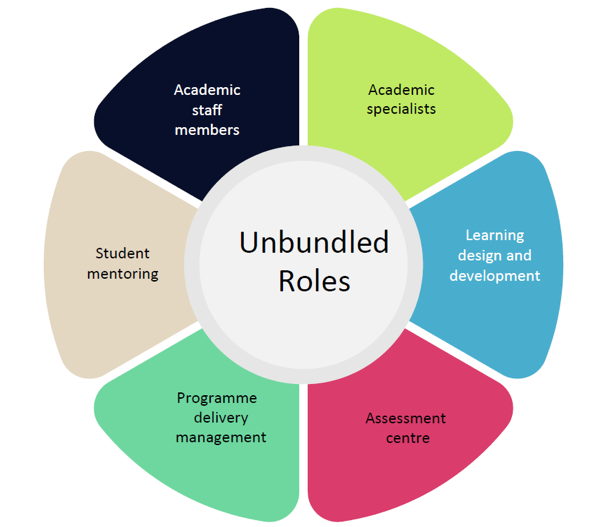

The approach taken by Open Polytechnic when unbundling Faculty activity in this way, and reconceptualising the grouping of like activities, has resulted in establishing a role for the polytechnic’s academic staff that speaks directly to the key contributions that they are able to make to the experience that a learner has when engaged in ODFL delivery. This is illustrated in the graph shown below. By reference to this graph, along with the activities shown in the preceding depiction, the role of the academic staff member now has direct association with the activities of: teaching, [maintaining and enhancing] subject matter expertise, and research (applicable to academic staff who teach on degree level programmes). Similarly, the identification of alternative groupings of activities has resulted in the assignment of these to other roles in the organisation.

The activity groupings shown here have been used in the TCP as the building blocks for conceptualising and creating an organisational structure that facilitates the work of the polytechnic’s specialised staff in a task-related whole.

In Figure 3 shown below the activity groupings shown in the preceding section are attached to roles and functions in the newly transformed organisation. By referring to the two graphical depictions together it is possible to associate the activity groupings with the roles and functions in the new organisation structure.

Figure 3: Logically arranged activity groupings

The reorganisation of the Open Polytechnic based on the model that is described here has resulted in the creation of an entirely non-traditional organisational structure. In the achievement of this reorganisation all of the component activities found in any traditional tertiary education provider are also present in the polytechnic. The critical difference being that the component activities are now aligned with what is the distinctly different model of educational delivery characterised in the ODFL model.

A key foundation stone in building a flexible learning experience for ODFL learners is the provision of summative assessment that is independent of their engagement with learning and teaching. The pedagogical approach adopted in OPNZ’s TCP acknowledges that formative assessment is to be integrated with the learner’s learning and teaching experience.

Summative assessment is to be available to the learner in a way that provides them with greater control of their own assessment decisions. Deciding when they are ready to be assessed and choosing assessment formats most suited to their learning style and the outcomes to be achieved, are examples of how the assessment environment is able to be structured to be more learner‑driven.

In OPNZ’s TCP the establishment of an Assessment Centre is a critical shift in organisational thinking that is expected to realise the aspirations of the TCP in this regard.

As our transformation programme progresses, we seek to embed an educational model and ethos that promotes enhanced learner agency, flexibility and mobility. The learner journey will support significantly greater student choice over enrolment, study progress and volume, and assessment.

Our education design must lead development of stackable, modular courses of study. Our strategic insight unit must develop our analytic capability (both quantitative and qualitative) to generate the data and feedback that will drive quality improvement and inform our learner interventions. We need to enable 365 admissions; and the Assessment Centre must adopt the on-demand, challenge assessment policy.

Alongside this transformation effort, we are maintaining continuous iterative development of our digital learning platform, alongside ongoing enhancement of our education technology more generally.

Beyond innovating to meet the changing needs of its core constituency of learners, Open Polytechnic’s digital and organisational transformation opens the way to expanded collaboration with other education providers. In terms of organisational strategy and positioning, Teixeira, Bates & Mota argue that as part of ensuring their future role it is critical that specialist ODFL providers partner with traditional higher education institutions with the aim of building system capability (Teixeira, Bates & Mota, 2019).

In a New Zealand context, there is potential for networked institutions to share learning products and services to enhance overall system efficiency and responsiveness, a view strongly reflected in the Government review of the ITP sector noted above.

In his Cabinet paper launching the review, the New Zealand Minister of Education, Hon Chris Hipkins, said: “To help us achieve a world-class skills system, I believe there is value in exploring how the network of tertiary education providers can operate more as a system – so that we can use the resources of the network as a whole to achieve high quality provision across the country.”

It is within this context that a transformed ODFL specialist can contribute a unique capability within a network of conventional institutions. In their article “Openness, Dynamic Specialization, and the Disaggregated Future of Higher Education”, Wiley & Hilton (2009), suggest that higher education providers respond to changes in technological innovation by increasing connectedness, personalisation, participation and openness. Within their five critical functional areas of institutional organisation, both “structuring and access to content” and “tutoring and learning support services” domains provide opportunities for specialist ODFL institutions to contribute to collaborative networks. The digital capability and “unbundled” organisational flexibility OPNZ is developing, significantly enhances its ability to support other organisations in these domains, and within the wider national network of vocational education and training in New Zealand.

The need for enhanced learner centricity, increased scalability, improved flexibility and interoperability is driving the transformation of ODFL in higher education. Technology enhanced learning and more open educational practices are becoming mainstream in both higher education organisations and non-formal providers. Consequently, specialist ODFL organisations must identify and deepen the unique contribution they make both for their constituency of learners and to the wider system of tertiary education provision. Open Polytechnic of New Zealand has undertaken a major programme of digital and organisational transformation that further differentiates its delivery and enhances its flexibility as an online learning organisation. This institutional reengineering that disaggregates functions and unbundles processes and services, holds potential for both improved performance and enhanced partnering opportunities within a network of provision.

Bates, T. (2015, June 30). What can past history tell us about the Athabasca University ‘crisis’? Retrieved from https://www.tonybates.ca/2015/06/30/what-can-past-history-tell-us-about-the-athabasca-university-crisis/

Daniel, J. S. (1998). Mega-universities and knowledge media: Technology strategies for higher education. London, England: Kogan Page.

Daniel, J. S. (2010). Mega-schools, technology, and teachers: Achieving education for all. New York, NY: Routledge.

Daniel, J. S. (2018). Open universities: Applying old concepts to contemporary challenges. Retrieved from http://sirjohn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/20180630_IRRODL_Paper.pdf

Eckel, P. D., & Kezar, A. J. (2003). Taking the reins: Institutional transformation in higher education. Phoenix, AZ: ACE/Oryx Press.

Garrett, R. (2018). Whatever happened to the promise of online learning? The state of global online higher education. Retrieved from http://www.obhe.ac.uk/documents/view_details?id=1091

Keegan, D. (1994). The competitive advantages of distance teaching universities. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 9(2), 36–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051940090206

Office of the Minister of Education (2018). Approach to reforms of the institutes of technology and polytechnic subsector. Retrieved from http://education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Information-releases/2018-releases/Final-redacted-ITP-Cabinet-paper.pdf

Rumble, G. (1992). The competitive vulnerability of distance teaching universities. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 7(2), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051920070205

Teixeira, A. M., Bates, T., & Mota, J. (2019). What future(s) for distance education universities? Towards an open network-based approach. RIED: Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 22(1), 107–236. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.22.1.22288

Wiley, D., & Hilton, J., III. (2009). Openness, dynamic specialization, and the disaggregated future of higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10(5), 1–7. Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/768/1415

Authors:

Dr Caroline Seelig is Chief Executive of Open Polytechnic, New Zealand. Dr Caroline Seelig has over 25 years’ experience as a senior manager in New Zealand’s tertiary education sector. Caroline is an Honorary Fellow of the Commonwealth of Learning. Email: Caroline.Seelig@openpolytechnic.ac.nz

Alan Cadwallader Executive Director, Learning Delivery, Open Polytechnic of New Zealand. Commencing with Open Polytechnic at the beginning of 2015, Alan has brought to his role a significant depth of experience in the New Zealand vocational tertiary education sector. He has an MBA from Otago University and a research-based Masters in Management from Massey University. He also holds certification in adult teaching and learning. Email: Alan.Cadwallader@openpolytechnic.ac.nz

Doug Standring is Executive Director Marketing and Communications at Open Polytechnic, New Zealand. Doug specialises in marketing and communications in the international ODL environment, and distance learning strategy, management and business models. Doug’s 20-year career in tertiary education in New Zealand and the United Kingdom spans strategic planning, brand, digital and search marketing, corporate communications, business development and partnerships, product and service innovation, and transnational education. Email: doug.standring@openpolytechnic.ac.nz

Cite this paper as: Seelig, C., Cadwallader, A., & Standring, D.(2019). Transformational Change in Delivery at Open Polytechnic, New Zealand. Journal of Learning for Development, 6(1), 37-48.