VOL. 4, No. 3

Abstract: Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”, emphasises the need for “providing women and girls with equal access to education, health care, decent work, and representation in political and economic decision-making processes [which] will fuel sustainable economies and benefit societies and humanity at large” (UN, 2015). Millions of girls are forced into early marriage for economic and cultural reasons and denied the opportunity for education. Within the context of sustainable development, it is critical to raise awareness among communities that child marriage has wide ranging negative consequences for development and that allowing girls to have education and training can add enormous value to their society as well as their personal and family lives. This study aims to identify the role of community engagement and local community organisations in contributing towards ending child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) through ensuring equitable access of marginalised and out-of-school girls to education and training. The study was based on data collected from surveys that had been administered to 755 out-of-school girls, affected by CEFM in both urban and rural areas of three selected South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC) countries, that is, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India.

A growing number of young adolescents are out of school, with the global total reaching almost 65 million in 2013. Adolescents of lower secondary school age (typically 12 to 15 years) are almost twice as likely to be out of school as primary school-age children, with one out of six (17%) not enrolled. (UNESCO Institute for Statistics [UIS], 2015). The hardest to reach children are still out of school. They are poor, rural and, often, girls (UIS & UNICEF, 2015).

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, “achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”, emphasises the need for “providing women and girls with equal access to education, health care, decent work, and representation in political and economic decision-making processes [which] will fuel sustainable economies and benefit societies and humanity at large” (UN, 2015). Gender equality is not only a fundamental human right, but it is also an imperative, for peace and sustainable development. With Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4), the international community has pledged to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.” (UNESCO, 2015a). The onus is on all stakeholders to make a contribution in realising the SDGs in their entirety.

The following factors are raised in the literature as some of the significant causes for girls not attending school in the countries of this study:

For the purpose of this study the authors only focused on one of the causes, early marriage, for girls not attending school. While being in school is not enough to prevent child marriage, being out of school certainly increases the likelihood of it. Child marriage is not only a painful reality but is also a grave violation of the rights of children. Globally, 720 million women alive today were married before their 18th birthday, and every year, they are joined by another 15 million child brides – the equivalent to the entire population of Mali or Zimbabwe (UNICEF, 2016). The picture of child marriage is more alarming in Sub-Saharan Africa and in South East Asian countries. Although there are slight variations in the reasons, child marriage impacts negatively on the socio-economic progress of these countries.

“Child marriage denies a girl her childhood, disrupts her education, limits her opportunities…” (Government of Canada – UNICEF, 2015). Millions of girls are forced into early marriage for economic and cultural reasons and denied the opportunity for education. If resource-poor families are to invest in the education of their children, boys receive priority. However, if education is both affordable and flexible, girls, too, can have the opportunity to participate without disrupting their responsibilities in the home and the family. Furthermore, if girls are taught the skills necessary for gaining a livelihood, they can be a major source for supplementing the family income.

“Child marriage is rooted in gender inequality; and can be sustained through entrenched discriminatory social norms, poverty, and lack of education or even due to misplaced perceptions of providing protection for girls during a time of increased instability when girls are at a higher risk of physical or sexual abuse” (World Vision UK, 2016). Within the context of sustainable development, it is critical to raise awareness among communities that child marriage has wide ranging negative consequences for development and that allowing girls to have education and training can add enormous value to their society as well as their personal and family lives.

GIRLS Inspire is a Commonwealth of Learning (COL) project to provide schooling and skills development to some of the world’s most vulnerable and hard-to reach girls. Community organisations in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Mozambique and Tanzania are mobilised to leverage the power of open and distance learning (ODL) to end the cycle of child, early and forced marriage (CEFM) and to address other barriers that prevent girls’ economic participation (COL, 2016). The GIRLS Inspire project believes that labour market, employment friendly and community oriented, open schooling will lead to a better livelihood, changes in life-cycle behaviour and postponement of girls' early marriage. The catalysing strategy, therefore, integrates education and learning within the whole community, with its traditions and practices, to support girls' education and learning. The project has the following outcomes:

To achieve the outcomes, partners, with support from the community, trained approximately 25,000 women and girls in vocational and life skills. The vocational skills are context specific and based on the needs of the girls and the labour and employment market. The vocational skills (29 courses in total) vary in the different countries and include the following: tailoring, being a beautician, goat rearing; fashion designing; cloth and bag making; candle making; mobile phone repairs; carpentry, flood resistant crop raising; poultry rearing; curtain making; cooking, and tie and dye making. The training took place at safe learning environments using a blended approach that involved one or more of the following: print, computers, the Aptus, videos, radio and television. Partners also used mobile training units for hard to reach communities, including Bus and the Boat schools. The Life Skills component, as in the case of vocational skills, was contextualised based on the needs of the girls. However, the content for the 35 Life skills courses were developed around the following themes: financial literacy, Health and hygiene and social rights. Furthermore, partners facilitated girls’ access to employment, microfinancing, entrepreneurship, internship and the opening of bank accounts.

Bangladesh and India feature among the top 10 countries where the highest rates of child marriage prevail. In South Asia approximately one in two girls is married off before the age of 18, making South Asia the region with the highest prevalence of child marriage in the world. Bangladesh has the highest rate of child marriage in the region (52%), followed by India (47%), Nepal (37%) and Afghanistan (33%). According to the study “Asia Child Marriage Initiative: Summary of Research in Bangladesh, India and Nepal” conducted by International Center for Research on Women (ICRW Plan, 2013, p. 17) the causes of child marriage include normative and structural factors as listed below:

The same report reflects on Community leaders’ response to child marriage as follows:

Community leaders and government officers felt that there has been positive changes in the situation regarding child marriage, and that there are fewer child marriages. They credited the work of the government and NGOs in increasing awareness about the issue. They also mentioned the availability of education, which makes it easier for girls to stay in school longer. Some also mentioned the need to eradicate poverty as a means of eliminating child marriage. However, they felt that there was a need for greater awareness about the negative consequences of child marriage and better implementation of legislation. They also mentioned the need for cooperation between the government and NGOs and the critical role of parents and families. (ICRW Plan, 2013, p. 22)

The survey countries resemble each other in their profiles. However, there are significant variations in terms of poverty levels and female literacy rates. Table 1 depicts the basic country profiles of the participating three countries. It is noted that the illiteracy rate among females is still a big challenge. Although other indicators are encouraging, Pakistan seems to lag behind in terms of female literacy, compared to India and Bangladesh.

Table 1: Country Profiles

Country |

Population |

GNI per capita (US$) |

Poverty head count |

Literacy rate |

||

All |

Female |

Male |

||||

Bangladesh |

160 million |

1,190 |

31.5 (2010) |

61.5% |

58.5% |

64.6% |

India |

1.311 billion |

1,590 |

21.9 (2011) |

72.1% |

62.8% |

80.9% |

Pakistan |

189 million |

1,440 |

29.5 (2013) |

56.4% |

42.7% |

69.6% |

Sources: World Bank, 2015; UNESCO, 2015b

Table 2 shows that child marriage is much higher in Bangladesh, followed by India and Pakistan, respectively.

Table 2: Country and Child Marriage Statistics

Country |

Legal marriage age |

Child marriage (Female) |

|

Male |

Female |

||

Bangladesh |

21 |

18 |

52% |

India |

21 |

18 |

47% |

Pakistan |

18 |

16 (18 in Sindh |

21% |

Sources: UNICEF, 2016

The study aims at identifying the role of community engagement and local community organisations to contribute to ending CEFM through ensuring equitable access of marginalised and out-of-school girls to education and training. The study explored the following:

The study is based on the data collected from surveys, which were administered to 755 out-of-school girls,- affected by CEFM in both urban and rural areas of Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India. A structured questionnaire was used for data collection. The data used in this research are baseline and endline data. Baseline surveys were conducted immediately following girls’ registration into the project, and endline surveys were conducted after the completion of project activities. The time gap varied among the three countries because the training model was contextualised and was not necessarily the same time period. The time between a baseline and endline survey could be five to six months. While the study is aimed at identifying the existing status of the girls who dropped out of school and the structure of the community engagement in favour of their learning, the impact of COL’s intervention for mainstreaming girls’ education and skill training can be investigated at endline, compared with the baseline findings.

Standardisation procedures were taken at baseline and endline points to ensure the validity and reliability of data. A web-based data collection platform was used for standardisation and efficiency. FluidSurvey was at first procured but due to the company shutting down its operations, Survey Gizmo was used for the last quarter of the data collection. Both platforms were chosen due to their capabilities for offline data collection, mobile device compatibility and multiple-language hosting. As a result, survey questions were structured to provide restrictions and guidance. All survey tools require the assigned data collector to provide their name at the beginning of each response, which allows administrators to query specific survey responses as needed. Responses were then streamlined into one hub, regardless of the remoteness of project locations and the language used.

Monitoring and Evaluation Focal Points (FPs) were also appointed in each country to act as champions and to create a data-driven culture within their organisations. They received monthly and on-demand training from GIRLS Inspire on M&E concepts and data collection procedures. Resources were also provided to clarify and define terms used in the survey tools (e.g., gender-sensitive, social rights, etc,). Thereafter, they were responsible for using standardised training resources to cascade the skills acquired to appointed field data collectors.

Field data collectors were recruited based on their ability to speak the local language and to establish connections with the survey respondents. When male data collectors were in the field, they were often accompanied by female data collectors, so that women and girls could feel at ease, and parents would allow their daughters to speak to men. Training was also provided to ensure the data was collected in an ethical way. To ensure girls’ safety and to minimise social desirability bias, field data collectors were instructed to emphasise the anonymity and confidentiality of the survey, and to conduct the surveys in safe environments for the respondent. Each baseline and endline tool opened with the purpose of the study and with the explanation that participation is voluntary and responses will remain confidential. Consent forms for guardians of girls under the age of 18 were also provided.

Across the three countries, communities and villages were selected for project operations, according to the prevalence of school dropout amongst girls and incidences of child marriage.

In Bangladesh, 64 villages in the Pabna and Natore Districts of the Rajshahi Division were selected due to their vulnerability to the monsoon season, which limits road access.

In India, the Satara district of Maharashtra has a high incidence of school dropout among girls for reasons such as migration, poverty, and long distances to school. In response, Mann Deshi Foundation focused on reaching women and girls in 150 villages across Satara through community negotiated, safe learning environments and mobile business schools.

In Pakistan, 37 communities were identified in Hyderabad, Multan, Rawalpindi and Peshawar, where female labour participation is low. The overall target was to reach 20,000 women and girls in these areas within the one-year project. The baseline-endline study was designed to capture the perspectives of not only the women and girls but also the community as a whole.

The study collected data among a random sample of women and girls in the intervention who resided within the selected areas. With an acceptable margin of error of 5% amongst the target population of 20,000 girls, the recommended sample size of 377 girls was increased in order to account for possible attrition. An effort was made to survey the same group of respondents at baseline and endline. In the end, 755 women and girls were able to complete the study and were matched at both baseline and endline points.

The data collected in the study was analysed with the use of SPSS software. Sampling for the qualitative research was purposive (rather than random). Table 3 below shows the distribution of the respondents in the study. A total of 755 girls of different age groups in three neighbouring countries were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Similarly, 166 community leaders were also interviewed at baseline and 146 at endline to investigate their existing engagement in girls’ education. As for organisational staff, 24 project staff were surveyed at baseline.

Table 3: Girls’ Age Range by Country (N = 753)

|

Girls’ Age Range |

Total |

||||||

10-14 |

15-17 |

18-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

||||

Country |

Bangladesh |

Count |

8 |

77 |

211 |

39 |

1 |

336 |

|

22.2% |

39.1% |

46.5% |

61.9% |

33.3% |

44.6% |

||

India |

Count |

20 |

57 |

115 |

16 |

1 |

209 |

|

|

55.6% |

28.9% |

25.3% |

25.4% |

33.3% |

27.8% |

||

Pakistan |

Count |

8 |

63 |

128 |

8 |

1 |

208 |

|

|

22.2% |

32.0% |

28.2% |

12.7% |

33.3% |

27.6% |

||

Total |

Count |

36 |

197 |

454 |

63 |

3 |

753 |

|

|

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Marital Status

Table 4 shows that Bangladesh has the highest percentage of married girls among the three countries, followed by India and Pakistan. Of the total girls sampled in Bangladesh 63.7 % were married compared to 47.8% and 22.9% for India and Pakistan, respectively.

Table 4: Marital Status by Country

|

Country |

Total |

||||

Bangladesh |

India |

Pakistan |

||||

Married |

No |

Count |

121 |

98 |

162 |

381 |

% within Country |

36.0% |

46.9% |

77.1% |

50.5% |

||

Yes |

Count |

214 |

100 |

48 |

362 |

|

% within Country |

63.7% |

47.8% |

22.9% |

47.9% |

||

De facto union |

Count |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

% within Country |

0.3% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.1% |

||

Prefer not to answer |

Count |

0 |

11 |

0 |

11 |

|

% within Country |

0.0% |

5.3% |

0.0% |

1.5% |

||

Total |

Count |

336 |

209 |

210 |

755 |

|

% within Country |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

||

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Dropout Grade Level

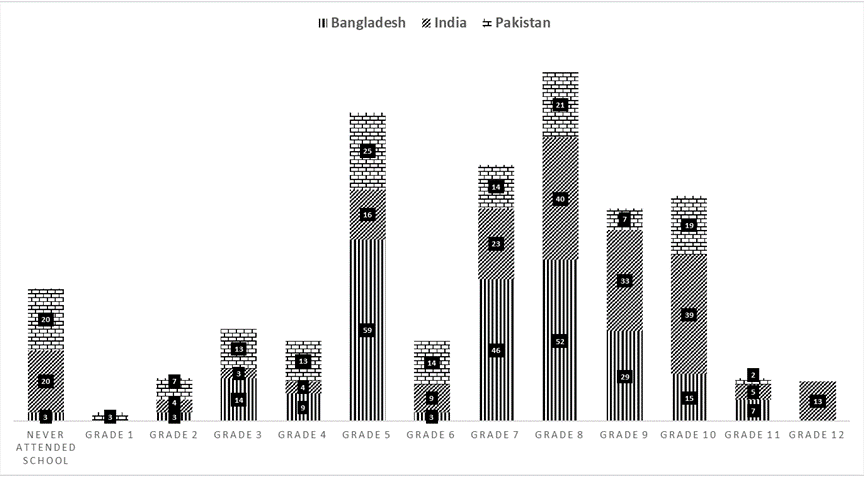

Figure 1 shows the dropout rates against the grade levels. While there is a variation of the dropout grade levels in the three countries the data shows that there are two periods where the dropout is high: one before completion of primary and one before completion of secondary school.

Figure 1 also shows that the respondent girls mostly didn’t continue their study up to the secondary grades. Among the girls who continued their study at post-primary levels, most of them dropped out before completion of their secondary education. The data shows that, overall, the highest dropout rate happens in Grade 8. However, in Bangladesh and India the highest dropout rate happens in Grade 5, where 7.1% of the respondent girls didn’t attend school. Although the rates vary from one country to another, girls’ dropout is a big problem in the participating countries.

Figure 1: Final Level of Schooling by Country

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

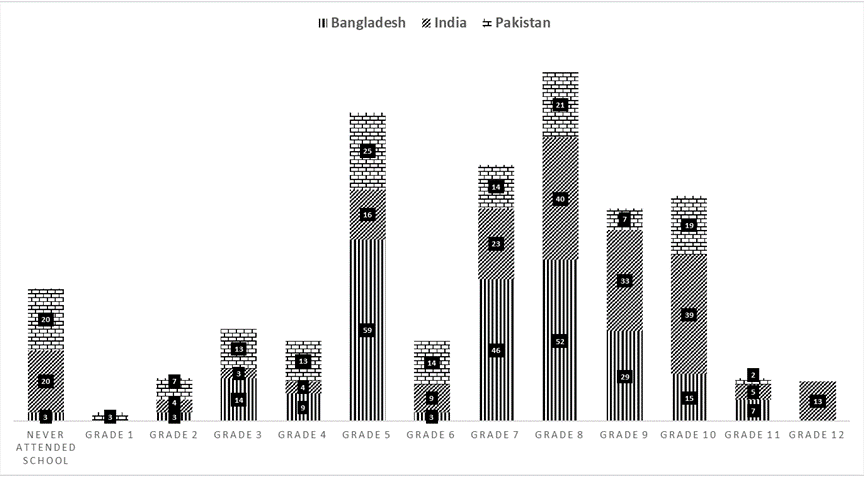

Reasons for Dropout from Education

Although there are several reasons for the girls to dropout at an early stage of their education, Figure 2 shows that overall poverty is the main reason for the respondent girls to dropout from education, followed by marriage. Other reasons for girls’ dropout include family crisis, distance between school and home, culture and domestic responsibilities. In Pakistan and India lack of family support is the second highest reason for dropout, compared to marriage in Bangladesh.

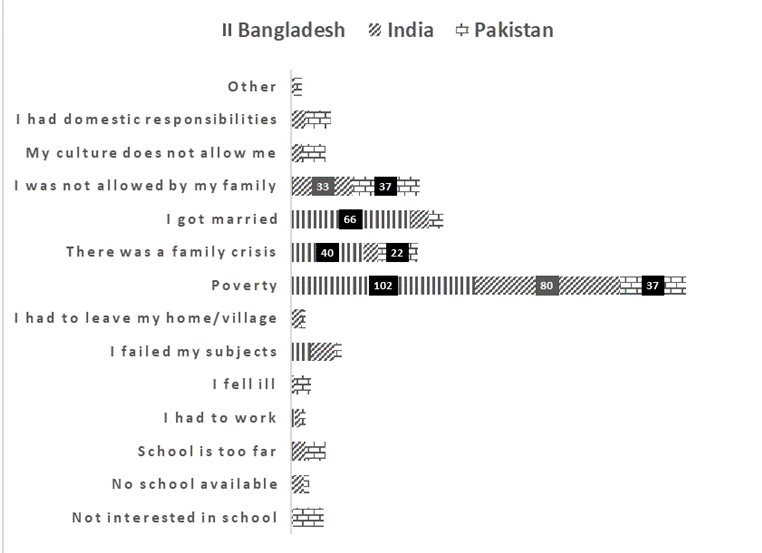

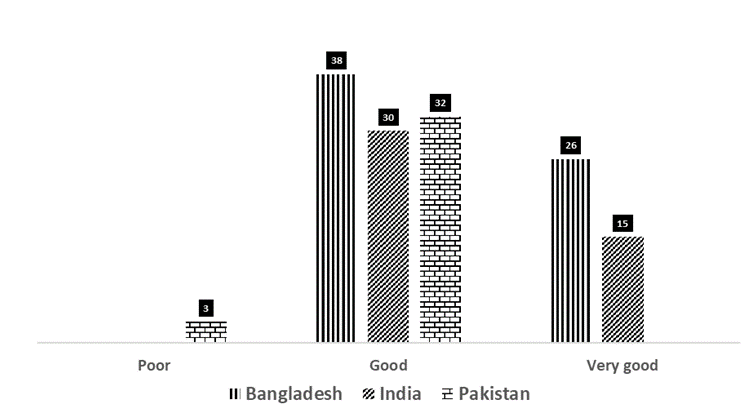

Limited Economic Opportunities for the Girls

Access to economic opportunities for the respondent girls seems to be very limited before they participated in the training. Their skill or freedom to work was not enough for them to be engaged in economic activities. They were mostly engaged in household activities to support their parents. Figure 3 shows that the majority of the respondent girls during the baseline rated their access to economic opportunities to be poor or very poor. They either didn’t find any opportunity to work or they were not even aware of the economic opportunities they could exploit.

Figure 2: Reasons for Dropping out of or not Attending School

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 3: Access to Economic Opportunities by Country

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

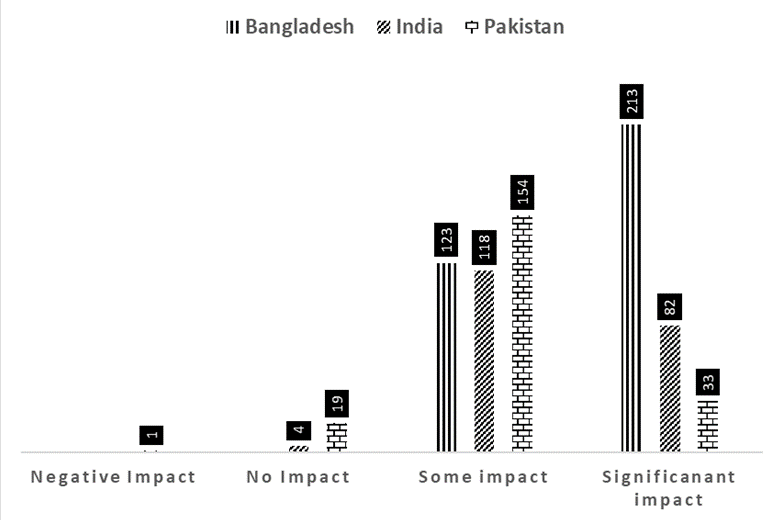

Figure 4: Training Impact on Access to Economic Opportunities

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016

The same respondents showed (Figure 4) a significant shift in how they rated their access to economic opportunities after the training. The majority indicated that the training had some significant impact on their access to economic opportunities. A very small number (24) indicated negative to no impact.

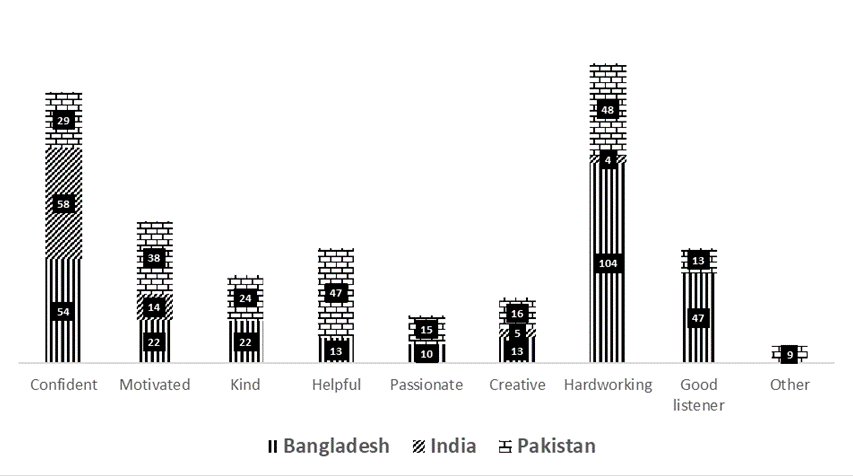

Girls’ Perception about their Qualities

The study also explored girls’ perceptions about their own qualities. It seems that the girls were fully aware of their qualities. Figure 5 summarises the perceptions of the respondent girls about their qualities. Overall, the top three qualities girls’ rated them in order from high to low were hardworking, confident and motivated.

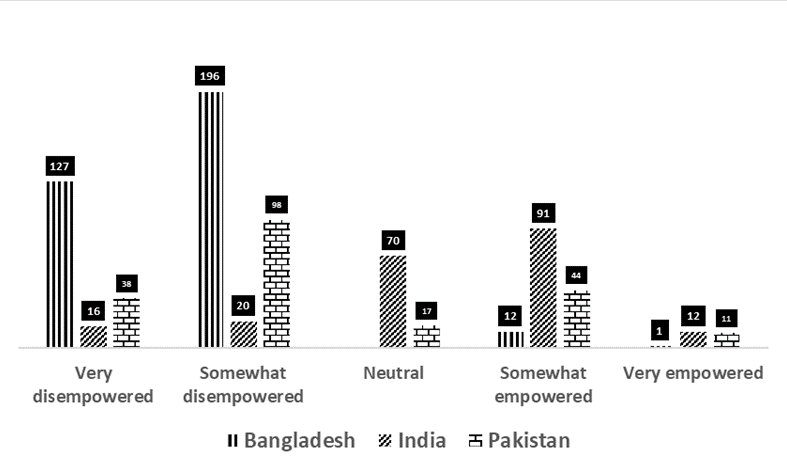

Ability to Contribute Family Decision Making

Girls and women’s participation in family decision-making is a challenge, however, it is important for gender equality and empowerment. The respondents were asked before and after the training on how they rated their ability to contribute to family decision-making. Figure 6 summarises the perceptions of the respondent girls and women regarding their contribution in family decision-making process before the training, and Figure 7 summarises it after the training. Figure 7 shows that the majority indicated that they are somewhat disempowered in the family decision-making process. A bigger portion of the respondents remained neutral, as they may not have had an opinion on any role they have in the family decision-making process. In the endline study, Figure 7 also indicates a significant shift, where they indicated that the training had somewhat to significant impact on their decision-making.

Figure 5: Baseline – What Quality Best Describes You

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 6: Ability to Participate in Family Decision-Making?

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 7: Training Impact to Participate in Family Decision-Making

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016-2017

Desire to Have Education

The majority of the girls indicated their desire to have an education. Figure 8 shows that most of the girls from the participating countries showed a strong desire to continue with their tertiary education during the baseline study with a slight overall increase of the same at the endline. According to Figure 8 the biggest group who indicated that they did not want to continue tertiary education are from India.

Figure 8: Interest to Continue to Tertiary Education

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016-2017

Organisational Readiness For Girls Education

Organisational arrangement is important for girls’ equitable access to education. Table 5 summarises the organisational arrangement for girls’ education in the survey countries. It shows that organisational/institutional arrangements for girls’ education were not promising at its current stage. Most of the surveyed organizations in Bangladesh and Pakistan had a gender policy whereas the organisations in India did not have one. In terms of quality assurance policy, Bangladesh and Pakistan were well ahead, whereas the organisations in India did not have any quality assurance policy. In all three countries, the organisations seemed to be lagging behind in using technologies in their learning support and resource sharing. They were also behind in terms of ODL. The training programmes they provide were limited to face-to-face mode of delivery.

Table 5: Organisational Perspectives

|

Gender Policy |

QA Policy |

Protection by Tutors |

Flexibility in Learning Access |

||||||

|

Don’t know |

Yes |

No |

Don’t know |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

F2F |

ODL |

Pakistan (%) |

0 |

90 |

10 |

20 |

40 |

40 |

90 |

10 |

100 |

0 |

India (%) |

8.33 |

0 |

91.67 |

8.33 |

0 |

91.67 |

100 |

0 |

91.66 |

8.33 |

Bangladesh (%) |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

Source: Girls Inspire Reaching the Unreached Baseline Survey 2016

Community Engagement in Girls’ Education

This section reflects on the responses from Community Leaders. Community support is always considered as an important enabler for girls’ education. Traditional and cultural norms are rooted within the community and therefore it is important to engage the community in the education of the girls. In most of the cases, lack of community engagement makes girls education more difficult.

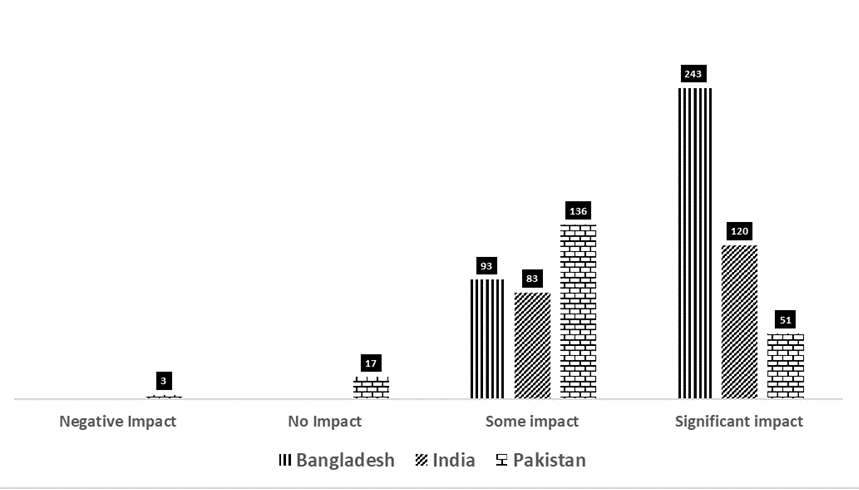

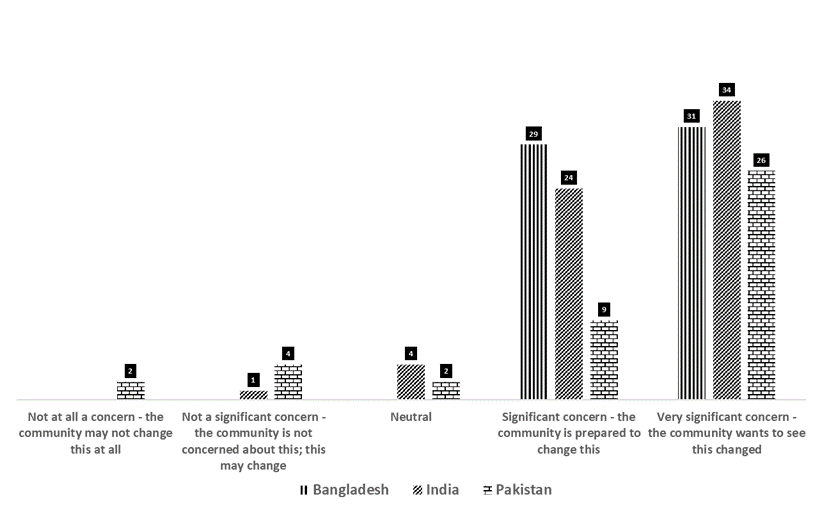

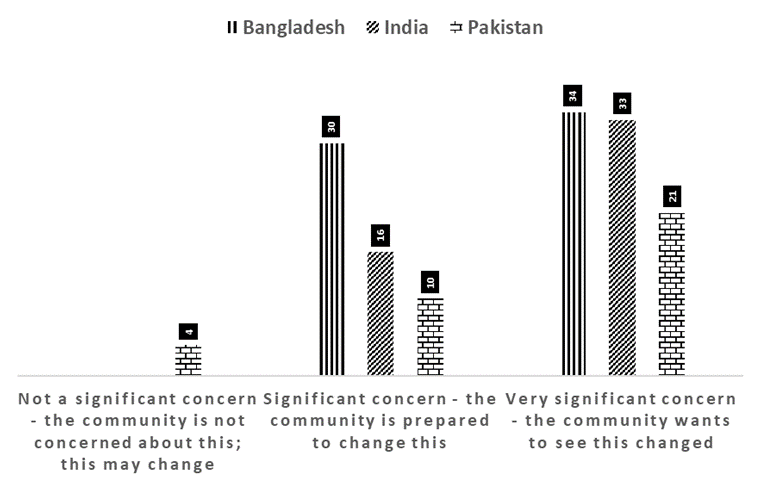

Community Concern about CEFM

From Figures 9 and 10, it can be seen that community leaders of all three participating countries were significantly concerned about CEFM and its impact on their society. In India and Bangladesh, community leaders seemed to be more concerned about the consequence of CEFM as compared to the same in Pakistan. Figure 10 summarises the endline data that indicates that the community leaders in all countries became more aware regarding CEFM and its impact, after the GIRLS Inspire initiatives. Now, most of them are significantly or very significantly concerned, compared to a very low proportion who are not concerned in Pakistan.

Figure 9: Child, Early and Forced Marriage as an Issue in the Community

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 10: Child, Early and Forced Marriage as a Concern after this Project Started

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016-2017

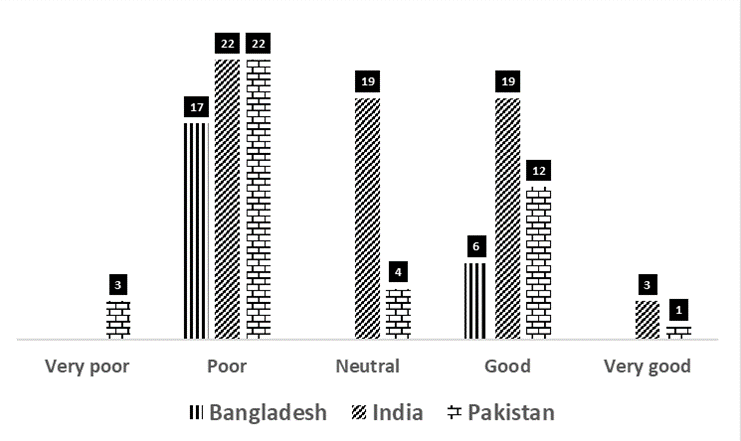

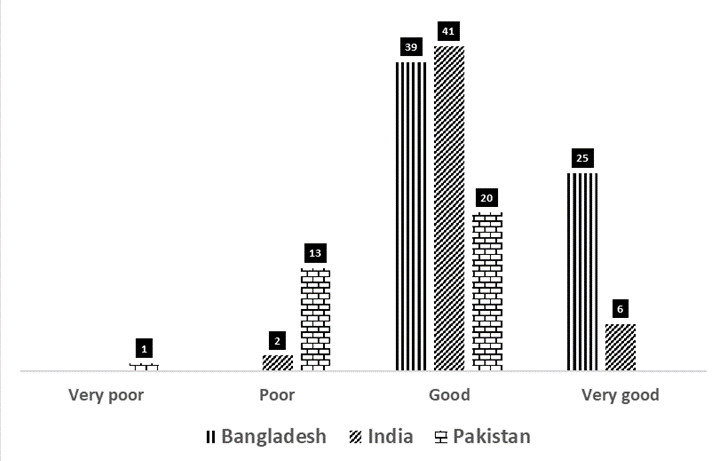

Employment Opportunities

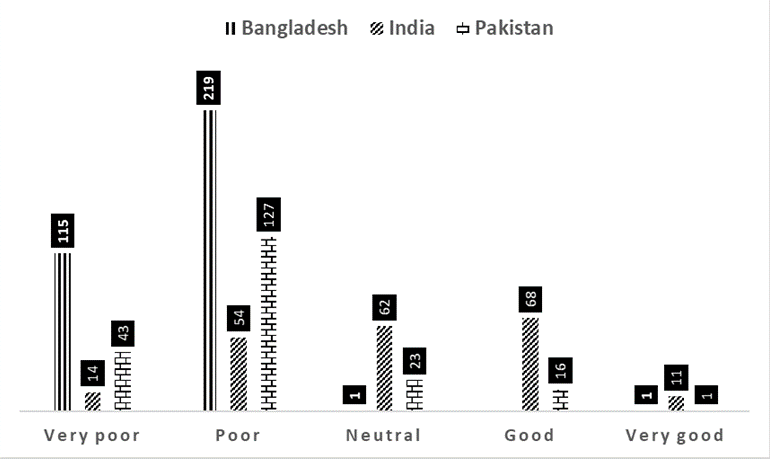

According to community leaders, the girls are in a disadvantaged position in terms of employment opportunities. Figure 11 (baseline data) shows that, employment opportunities for the girls in the communities are poor in all the survey countries. It is interesting to note that few of the community leaders remained neutral in sharing their views about the girls’ employment scope in the communities in India and Pakistan. It indirectly supported their reluctance about securing girls’ employment opportunities in the communities. However, the response of the community leaders in Bangladesh was significant regarding employment opportunities for girls, and most of them, too, acknowledged that employment opportunities for girls in Bangladesh were poor, except for a few who mentioned that the employment opportunity for girls were good. According to the endline data (Figure 12), the picture has changed significantly after the GIRLS Inspire intervention. The endline data in Figure 12 shows that the community leaders endorsed good employment opportunities for the girls in the communities. The scenario has been improved for all the survey countries, though the response of the community leaders in Bangladesh showed a very changed rating about the girls’ employability. An overall change in rating from poor to good and very good happened due to GIRLS Inspire intervention.

Figure 11: Employment Opportunities for Girls and Women in the Community

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 12: Employment Opportunities for Girls and Women in Your Community (Endline Data)

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016-2017

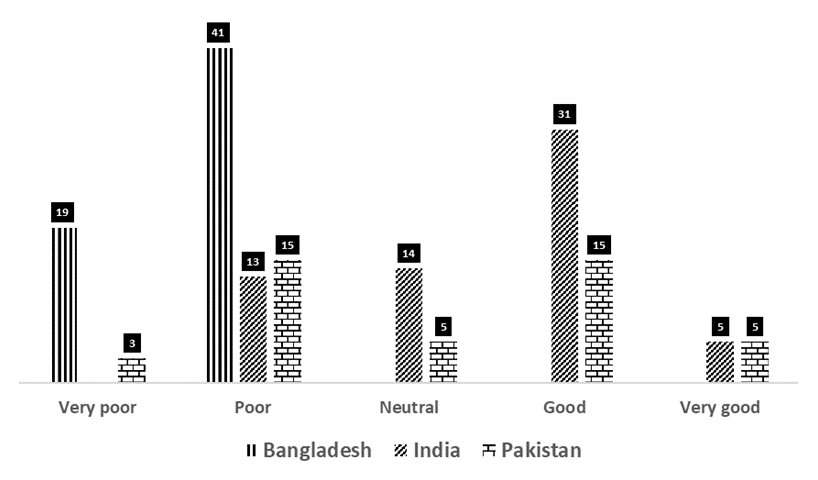

Community Support Toward Girls Education

Community support toward girls’ education seems to be very weak in Pakistan and Bangladesh as compared to India. Again, a significant number of respondent community leaders were reluctant to speak about the essentiality of the community support for girls’ education. Figure 13 (baseline data) shows the comparative figures on community support for girls’ education in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Figure 13 shows that the community support was poor towards women’s and girls’ education in Bangladesh, whereas, in India and Pakistan, it was relatively better. After the GIRLS Inspire intervention, as Figure 14 shows, community support for women’s and girls’ education has significantly improved. Most of the respondents specified that the community support in the survey area had improved to good or very good.

Figure 13: Community's support to women and girls' education

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Figure 14: Community's support to women and girls' education after the project started

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline-Endline Study, 2016-2017

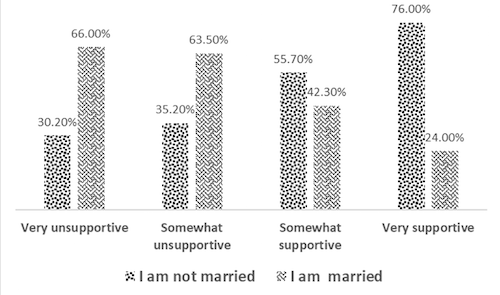

Family Support for Schools or Skills Training

Marital Status by Family Support for Schools or Skills Training

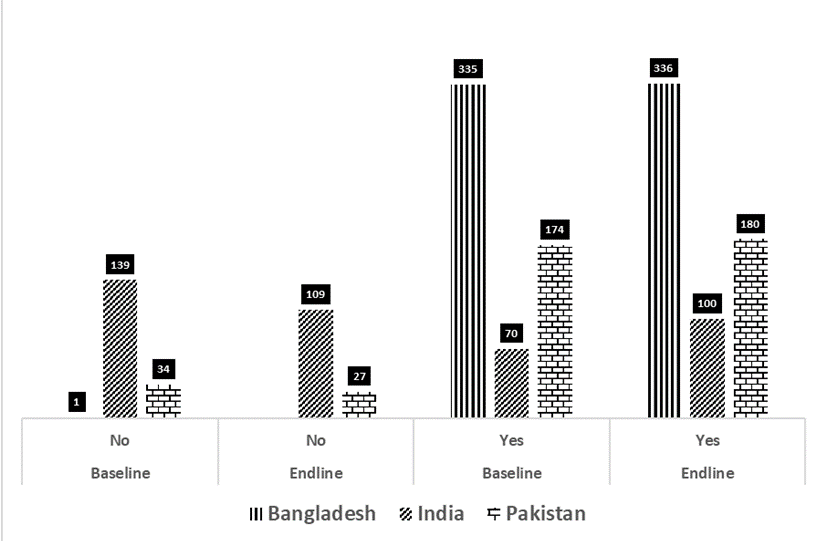

Figure 15 shows that family support for school or skills training to women and girls was low in the case of married women or girls, compared to that of the unmarried women and girls.

Table 6 shows that family support for schooling is, in general, low for married women or girls. Table 6 shows that unmarried girls received a higher level of family support for schooling. Married women and girls who got little family support for schooling were aged between 15 and 18. Most of them mentioned that their families were somewhat unsupportive for schooling after their marriage.

Figure 15: Marital Status by Family Support for School or Skills Training

Source: GIRLS Inspire – Reaching the Unreached Baseline Study, 2016

Age at Marriage and Family Support for School

Table 6: Age at Marriage by Family Support for School or Skills Training

Family Support for School |

Total |

||||

Age at Marriage |

Very Unsupportive |

Somewhat Unsupportive |

Somewhat Supportive |

Very Supportive |

|

Not married |

18 (34.0%) |

89 (35.5%) |

172 (57.7%) |

93 (76.9%) |

372 (52%) |

3 |

- |

- |

1 (0.3%) |

- |

1 (0.1%) |

11 |

- |

- |

2 (0.7%) |

- |

2 (0.3%) |

12 |

- |

- |

1 (0.3%) |

- |

1 (0.1%) |

13 |

2 (3.8%) |

3 (1.2%) |

6 (2%) |

- |

11 (1.5%) |

14 |

2 (3.8%) |

9 (3.7%) |

6 (2%) |

1 (0.8%) |

18 (2.5%) |

15 |

7 (13.2%) |

24 (9.8%) |

15 (5%) |

1 (0.8%) |

47 (6.6%) |

16 |

3 (5.7%) |

39 (16%) |

26 (8.7%) |

5 (4.1%) |

73 (10.2%) |

17 |

12 (22.6%) |

52 (21.3%) |

29 (9.7%) |

5 (4.1%) |

98 (13.7%) |

18 |

8 (15.1%) |

19 (7.8%) |

28 (9.4%) |

7 (5.8%) |

62 (8.7%) |

19 |

1 (1.9%) |

6 (2.5%) |

5 (1.7%) |

3 (2.5%) |

15 (2.1%) |

20 |

- |

2 (0.8%) |

2 (0.7%) |

2 (1.7%) |

6 (0.8%) |

21 |

- |

- |

2 (0.7%) |

1 (0.8%) |

3 (0.4%) |

22 |

- |

- |

1 (0.3%) |

2 (1.7%) |

3 (0.4%) |

23 |

- |

- |

1 (0.3%) |

- |

1 (0.1%) |

24 |

- |

- |

1 (0.3%) |

1 (0.8%) |

2 (0.3%) |

28 |

- |

1 (0.4%) |

- |

- |

1 (0.1%) |

Total |

53 (100%) |

244 (100%) |

298 (100%) |

121 (100%) |

716 (100%) |

Although girls’ education has multiple impacts on the socio-economic development of a nation, there are still a number of structural and economic reasons that blocks the girls’ education from becoming mainstreamed. Based on the data from COL’s GIRLS Inspire Baseline Survey 2016 and Endline Survey 2017, this paper addresses a triangular focus on the reasons of the girls’ dropout from education and recommends ways to improve it as follows:

The findings in the survey suggest that the interventions of GIRLS Inspire enhanced the opportunities for girls’ education and empowerment to ensure sustainable livelihoods. This study recommends the following steps for girls’ education to contribute towards ending the cycle of CEFM and improving girls’ participation in education through the engagement of the community and local organisations in the overall process:

This paper is a revised and updated version of a paper presented at the 8th Pan Commonwealth Forum held at Malaysia in December 2016. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for providing comments for revising the paper.

BBS. (2013). Gender Statistics of Bangladesh 2012. Dhaka. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Statistics and Information Division (SID). Ministry of Planning.

COL. (2016). Theory-of-change. Retrieved from http://girlsinspire.org/explore-our-theory-of-change/#our-vision

Government of Canada and UNICEF (2015). Accelerating the Movement to End Child Early an Forced Marriage Initiative – Consolidated Annual Progress and Utilization Report for the period of 1 April - 31 December 2014. UNICEF Canada (Unpublished report).

ICRW Plan. (2013). Asia child marriage initiative: Summary of research in Bangladesh, India and Nepal. Retrieved from http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/PLAN%20ASIA%20Child%20Marriage-3%20Country%20Study.pdf

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. (2007). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. Mumbai: IIPS. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FRIND3/FRIND3-Vol1andVol2.pdf

Siddhu, G. (2011). Who makes it to secondary school? Determinants of transition to secondary schools in rural India. International Journal of Educational Development, 31(4), 394-401.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). (2015). A growing number of children and adolescents are out of school as aid fails to meet the mark, POLICY PAPER 22 / FACT SHEET 31. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/fs-31-out-of-school-children-en.pdf

UIS & UNICEF. (2015). Fixing the broken promise of Education for All: Findings from the global initiative on out-of-school children. Montreal: UIS. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.15220/978-92-9189-161-0-en

UNESCO. (2015a). UIS sustainable development data digest: Leading the agenda for the production of data to monitor education 2030. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Pages/uis-sustainable-development-data-digest.aspx

UNESCO. (2015b). UNESCO data. Paris: UNESCO.

UNICEF. (2016). State of the world’s children. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/sowc2016/

United Nations (UN). (2015). Sustainable development goals. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

World Bank. (2015). World Bank data. Washington DC: World Bank.

World Vision UK. (2016). POLICY Paper: Ending child marriage by 2030 - Tracking Progress and identifying gaps. Retrieved form http://www.girlsnotbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Ending_Child_Marriage_by_2030.pdf

Zaidi, B., Sathar, Z., & Zafar, F. (2012). The power of girls schooling for young womens empowerment and reproductive health. New York: Population Council.

Authors:

Frances J. Ferreira is Senior Advisor, Women and Girls at Commonwealth of Learning, Canada. Email: Fferreira@col.org

Mostafa Azad Kamal is Professor of Development Economics, and Dean, School of Business, Bangladesh Open University, Gazipur, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Email: mostafa_azad@yahoo.com

Footnote