VOL. 4, No. 3

Abstract: Academics’ engagement in Open Educational Practices (OEPs) is critical for opening up higher education. It is in this perspective that the willingness to engage in such practices among academics in Rwandan public higher education was investigated with an agenda to trigger responsive actions. Via convenience/availability and volunteer sampling, 170 academics were invited to participate in the study and 85 of them completed and returned an email self-completion questionnaire. The results revealed that the majority of participants were willing to contribute to Open Educational Resources (OER) by publishing their work under an open licence. Participants were also willing to engage in diverse OEPs including 1) finding OER and evaluating their quality, 2) participating in and evaluating open courses, 3) aggregating OER, 4) adapting OER and open courses, and 5) assessing accomplishment from open learning based on OER and open courses for credit. National and institutional policies were found to be the potentially most important enablers of academics’ engagement in those practices. In the light of the findings, the researcher argues that the inclusion of more learners in the higher education system would make academics more impactful than simply the citation of their work, a stance that was reflected in subsequent responsive actions. This study may benefit institutions and policy makers who are interested in opening up higher education, especially the University of Rwanda that is expected to contribute significantly to the transformation of the country into a middle-income, knowledge-based society.

One of the most successful practices in OER production has been publishing journal articles and books under an open licence. Through this practice, full texts of academic articles and books have become increasingly available to users free of charge. In many cases, these users are granted permissions to download, adapt, and redistribute the work at no cost other than the one related to Internet access.

To understand the continuity of this practice, it is worth shifting attention to the other side of the coin. Commercial publishers came up with pathways for 1) publishing journal articles and books under an open licence, or 2) releasing earlier versions of journal articles and books under an open licence. In the first pathway, referred to as the Gold route (Weller, 2014), an article or a book is published under an open licence, but the author is required to pay some fee. Arguably, requiring authors to pay a fee for publishing their work under an open licence discourages their contribution to OER, and leads to exclusion of those who work in under-resourced settings and institutions that have no funds to cover the publication fee. In the second pathway, referred to as the Green route (Weller, 2014), authors are allowed to upload an earlier version of the article or book on their own websites or institutional repositories under an open licence but after a certain delay. This delay used to be for six months but there has recently been a tendency to extend it to many years, a practice that slows down the increase of openly licensed content.

Weller (2014) distinguishes another pathway to publish journal articles and books under an open licence that does not charge any fee to the author: the Platinum route. This route is open to both the users and the author of the content. The author only contributes the content for free and the publication fee is paid by other contributors/collaborators. Institutions benefit most from this pathway in that they can access and use the open content from the day of publication without any cost, neither on their part nor on the part of any member of their respective communities (Nkuyubwatsi, 2016a; Nkuyubwatsi et al., 2015). From the perspectives of proprietary, vanity and predatory publishers, the Platinum route may be not practicable and beneficial. From the perspectives of educational institutions, authors and publishers who are honestly willing to contribute to the open access and the open education agendas, the Platinum route is a practicable and sustainable response to an unsustainable increase of fees required to subscribe to proprietary journal articles and the practice of selling the articles in bundles that forces institutions to buy articles they do not need along with the ones they need.

The use of the large amount of existing openly licensed content has not been satisfactory (Lane, 2010; Ehlers, 2011; Conole, 2013). The adoption of OER may have been inhibited by many barriers including: 1) limited access to technologies (Wolfenden, 2012; Wolfenden, Buckler, & Keraro, 2012), 2) limited literacies (OECD, 2007; Rennie & Mason, 2010), 3) the lack of motivation linked to poor salary (Badarch, Knyazeva, & Lane, 2012), 4) the lack of incentives or rewards for OER production, use and sharing (McAndrew, Farrow, Law, & Elliott-Cirigottis, 2012), and 5) the lack of formal recognition of OER production, sharing and adaptation as academic practices (OECD, 2007).

In an effort to move from OER production to OER use to support learning and teaching practices, Open Educational Practices (OEPs) emerged around 2007. According to Geser (2007), the concept of OEPs was backed by advocacy from Open eLearning Content Observatory Services (ALCOS). The International Council for Open and Distance Education (n.d.) defines Open Educational Practices as:

… practices which support the production, use and reuse of high quality open educational resources (OER) through institutional policies, which promote innovative pedagogical models, and respect and empower learners as co-producers on their lifelong learning path.

According to Ehlers (2011), focusing on OEPs would address the whole OER governance community: policy makers, organisational and institutional managers or administrators, professionals and learners. Similarly, Bijsterveld & Dopper (2012) argue that the success of the transition from OER to OEPs depends on policy makers, management, instructors and learners.

To attract academics to OEP-related actions, the two factor theory also known as the hygiene-motivation theory (Turabik & Baskan, 2015) is worth considering. According to this theory, employees are disinterested and less productive when policies, working conditions, salaries, employee benefits, manager-subordinate relationships, promotion and occupational security are not satisfactory, which constitutes the hygiene factor. In the opposite direction, employees are responsible, aim to achieve institutional targets, are independent decision makers, seek advancement opportunities and personal development, and feel appreciated when they are highly satisfied, which constitutes the motivation factor. It is in this perspective that the current study was conducted as part of PhD research that investigated opening up higher education with a focus on the potential contribution of different stakeholders: learners, academics and policy makers/institutional leaders. The current paper reports only data on academics and responsive actions.

The research covered in the current paper was part of a broader PhD study that was conducted within the transformative paradigm. Transformative research falls within the critical research framework in that its purpose is political and practical: it is motivated by a social concern that the researcher wants her/his work to contribute to addressing. Transformative researchers are convinced that social justice can be restored by a political action that will be triggered by the contribution of their research (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005). Although transformative researchers collect quantitative and/or qualitative data that help them answer the research question or confirm a predefined hypothesis, their ultimate objective is to trigger positive changes or responsive actions to improve the prevailing situation.

Since transformative research is motivated by an issue of social concern and is driven by an agenda to contribute to addressing the issue, neutrality is not of interest to transformative researchers. From a transformative perspective, neutrality may lead to indifference/inaction that may constitute ethical blindness, according to Whiteman (2012). This is especially the case if the researcher’s contribution would improve the wellbeing of disadvantaged people but s/he deliberately avoids contributing for the sake of neutrality.

According to Dennis (2009), research methods and standards within the transformative paradigm tend to be rejected. This rejection may justify the scarcity of publications related to transformative studies. Rejection of transformative research may result from the researcher’s priority on catalyzing actions that address the issue of social concern over predefined methodologies, theories and prescribed guidelines. However, transformative research reports must be backed by responsive actions and positive changes that testify to the social impact of the study.

The study from which the current paper emerged had two major components: the Research component and the Parallel development component. In the Research component, the researcher conducted research on different enablers for opening up public higher education in Rwanda, including current and potential practices of academics in Rwandan public higher education. In the Parallel development component, the researcher engaged in different initiatives with an ultimate agenda to influence policies and practices that could contribute to opening up higher education in Rwanda.

Research on academics’ willingness to adopt/develop practices that may contribute to opening up public higher education in Rwanda was conducted at the University of Rwanda: the only public higher education institution in Rwanda which, hence, constitutes the entire public higher education sector in the country. This research was conducted in the light of the research question To what extent are academics at the University of Rwanda willing to contribute to OER and open courses, and adopt open educational practices? Prior to conducting the study, the researcher sought ethical approvals from the University of Leicester and the University of Rwanda. In addition, the researcher sought permissions to conduct research in each college of the University of Rwanda as he was advised by the university’s Directorate of Research, Technology Transfer and Consultancy.

Data were collected using an email self-completion questionnaire. Prior to the use of the self-completion questionnaire, the researcher sent it to experts for critical feedback. The experts confirmed that the data that could be gathered using the questionnaire could help answer the research question. Having the research questionnaire checked by experts added face validity (Bryman, 2012) to the research. The researcher also piloted the questionnaire in an effort to ensure reliability.

Participants were recruited via “convenience sampling” (Denscombe, 2010; Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011) also known as “availability sampling” (David & Sutton, 2011). To recruit participants, the researcher visited different campuses, met academics in their offices or staff rooms, talked to them about the study and invited them to participate. The researcher asked academics that voluntarily accepted to participate in the study to provide their email addresses so that an email questionnaire could subsequently be send to them. For those academics, being part of the sample depended on their presence when the researcher visited their respective campuses and their willingness to participate in the study. The researcher could not, however, meet some academics face-to-face for many reasons, including their travels abroad to study or attend professional development events. The researcher invited those who were in his digital social networks electronically by sending them a Facebook or Skype message. Only academics who had volunteered to participate were included in the sample. Volunteer sampling helped the researcher to include in the study participants who were interested and willing to participate. However, these willing participants’ views may have been different from those of other academics who did not volunteer to participate (Seale, 2012).

In total, 175 academics volunteered to participate in the study and provided their email addresses. However, emails sent to five of these addresses consistently bounced back. That is, the questionnaire was successfully emailed to 170 academics who constitute the sample in the study. Subsequently, the researcher sent to volunteers three weekly friendly reminders to complete and return the questionnaire.

Questionnaires were returned from 88 of the 170 academics who had received the email questionnaire: 85 of them completed the questionnaires and three of them returned the questionnaires without answers to questions that would help answer the guiding research question. The three questionnaires were invalidated. This gave a 50% return rate (85 out of 170 recipients of the email questionnaires returned them with valid answers).

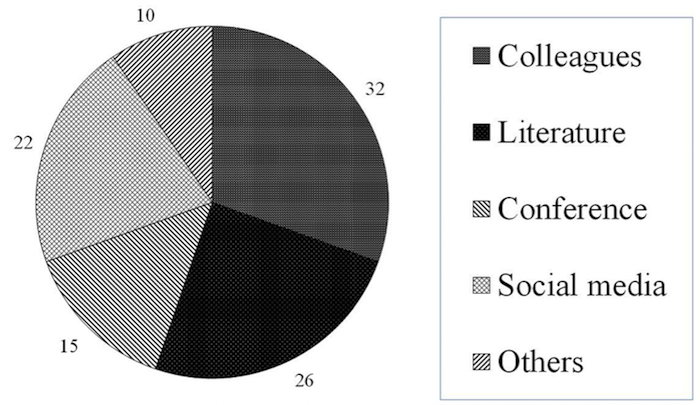

The majority of participants (58, or 68.2%) reported that they were aware of the concept of opening up higher education while 21 (24.7%) were unaware of this concept. As illustrated in Figure 1, 32 of those who were aware of opening up higher education had learned it from colleagues, 26 from academic literature, 22 from social media and 15 from academic conferences they had attended. Other sources of information on opening up higher education included the partnership between the University of Rwanda’s College of Medicine and Health Sciences and Tulane University (highlighted by two participants), workshops (two participants) and the researcher (two participants).

Figure 1: Sources of information on opening up higher education among academics

at the University of Rwanda

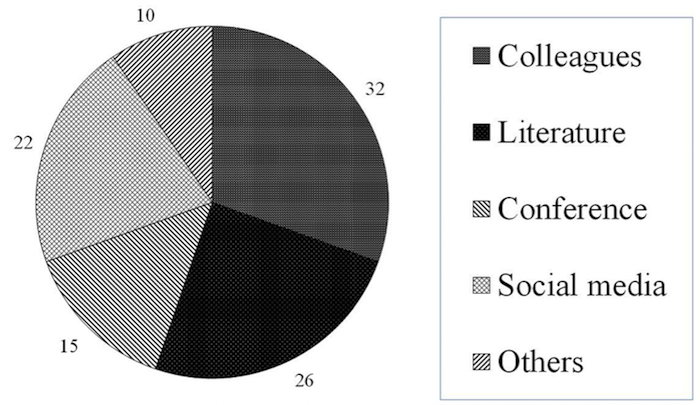

As illustrated in Figure 2, 68 participants (80% of all participants who returned valid data) supported the idea of making a list of competencies needed for the awarding of different qualifications publicly available. These include 52 participants (61.1%) who strongly agreed with the related statement in the questionnaire and 16 participants (18.8%) who agreed with it. Although a few academics commented on the statement, their comments were diversified. While some participants who supported the idea highlighted that this practice would help students focus on competence development and enable the profitability of education to the public, one participant expressed concern about learners’ laziness that could be triggered by the practice.

Figure 2: Academics’ opinions on opening up higher education

With regard to awarding the same qualifications to formal students and non-formal learners based on competencies they demonstrated via the same or similar assessment administered to both categories of learners, 44 academics (51.7%) supported the idea. These include 24 participants (28.2%) who strongly agreed with the related statement and 20 (23.5%) who agreed with the statement. Comments on this statement were also diversified. Two participants highlighted the need for effective assessment that would evaluate those competences. Two other participants emphasised the need to award qualifications based on competencies developed and evidenced rather than based on the learning mode. One of these two participants expressed his support as follows: “It is obvious and a matter of justice. The qualification should sanction the mastery of competencies not the mode of education delivery”.

However, not all comments were positive about the idea. One academic stated that non-formal learners are interested in qualifications rather than competence development. Another one stated that although competencies would be the same for both formal students and non-formal learners, recognition of formal education is a mandate.

Most participants saw national and institutional policies and strategies as the most important enablers for opening up higher education. Sixty-one participants (71.6%) agreed with the statement, “Opening content and assessment of open learning accomplishment can help open up higher education if they are supported by institutional policy and strategy”. Twenty-three of these participants (27%) strongly agreed with the statement while 38 (44.7%) agreed with it. When attention shifts to a national policy and strategy, 62 participants (72.9%) reported that this policy and strategy would enable opening up higher education. These include 42 participants (49.4%) who strongly agreed with the statement and 20 participants (23.5%) who agreed with it.

Participants’ opinions on the appropriate learning mode for competence development were also diversified. Forty-five participants (52.9%) expressed disagreement with the statement “Without attending higher education face-to-face, learners cannot develop competencies required for academic credit and qualification”. These include 27 participants (31.7%) who strongly disagreed with the statement and 18 participants (21.1%) who disagreed with it. Comments provided on the statement highlighted that courses that require experiment and practical work would necessitate face-to-face sessions. Some other academics stressed the role of the learners and one of them emphasised this role in these words: “It can depend on the learner if he/she is lazy or hard worker”.

Opinions tended to be more distributed when the statement applies to participants’ respective departments and the nature of courses in those departments. Nineteen participants (22.35%) strongly disagreed with the statement “Due to the nature of the field of study and courses, learners in my department can develop competencies needed for qualification via only the face-to-face mode”, while 14 others (16.47%) disagreed with it. A similar number of participants (14 or 16.47%) strongly agreed with the statement, while 12 participants (14.11%) agreed with it. Comments on this statement reiterated that modules that have experimental, clinical or practical components would need face-to-face sessions.

Participants in the survey responded to the statement: “There is no way the concept of opening up higher education in Rwanda can be applied without undermining quality”. Thirty participants (35.29%) strongly disagreed with the statement, nine (10.58%) disagreed with it, 12 (14.11%) agreed with it and 10 (11.76%) strongly agreed with it. Eighteen participants (21.17%) were neutral. Comments that expressed concerns on quality degradation if an agenda to open up higher education is undertaken were provided. These concerns were mainly triggered by inadequate infrastructure, the lack of academics’ preparedness and the lack of access to technologies by learners. On the optimistic side, one comment highlighted that different stakeholders can work on opening up higher education without undermining quality.

Academics’ opinions on opening up higher education with a particular focus on technological infrastructure was captured in the statement, “I think opening up higher education cannot be successfully implemented in Rwanda because there are no technologies to make it happen”. Thirty-three participants (38.82%) strongly disagreed with the statement and 17 participants (20%) disagreed with it. Eighteen participants (21.17%) were neutral on the statement, five participants (5.88%) agreed with it and eight participants (9.41%) strongly agreed with it.

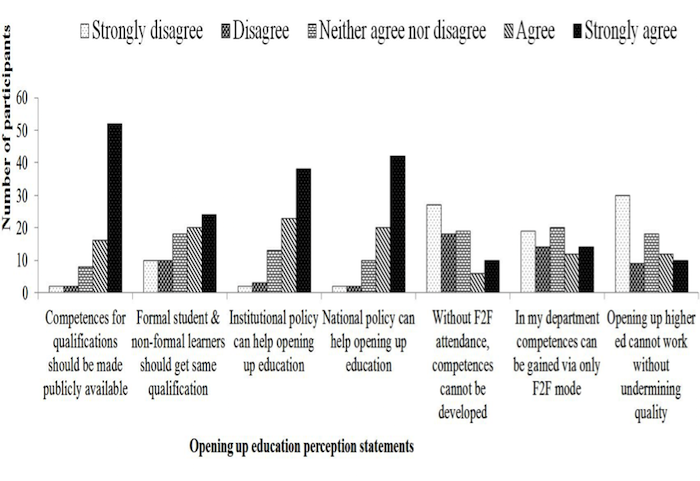

Comments on this statement tended to agree that the basic technologies to open up higher education are available in Rwanda. The comments also agreed on the need to upgrade the existing technological infrastructure progressively. The most important barrier was rather the lack of enabling policies. Other barriers that were highlighted included the lack of political will, the lack of related competencies among academics, the lack of awareness and the lack of involvement of all stakeholders. Only two of 14 comments on this statement highlighted that technological infrastructure is not enough to successfully open up higher education in Rwanda, but one of the two participants who made such comments saw a valid solution in the statement, “I think opening up higher education can be successfully implemented in Rwanda if the Ministry of Education, the University of Rwanda, academics and learners are all involved and develop ownership”. Academics’ responses on this statement will be detailed in the following subsection.As indicated in Figure 3, most of participants have not published content under an open licence, but were willing to do so. Fifty-seven participants (67%) strongly disagreed with the statement that claimed that they would not publish under an open licence because they would lose some benefits and five others (5.88%) disagreed with it. Fifty-two participants (61.1%) expressed their willingness to publish under an open licence if the institution accepts this practice. Similarly, 61 participants (71.7%) were willing to publish under an open licence if this practice does not incur more cost and their open publications lead to academic promotion. Although academics who thought they would lose some benefits by publishing under an open licence were not numerous, it is worth noting the concerns they raised. One of them highlighted that s/he prefers to publish in high impact journals that are often not open.

Figure 3 Academics’ willingness to contribute to OER

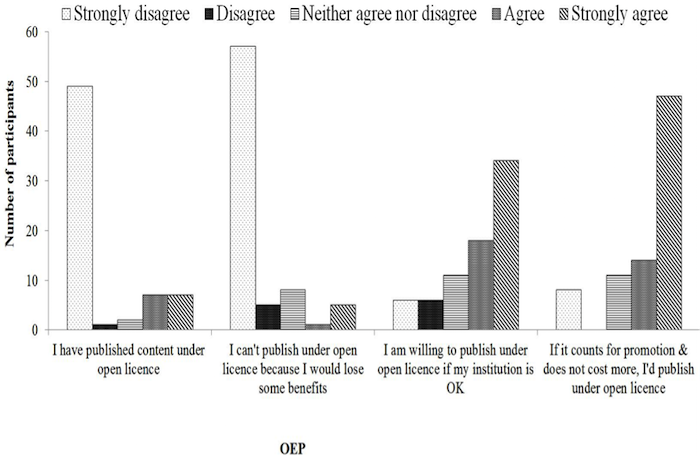

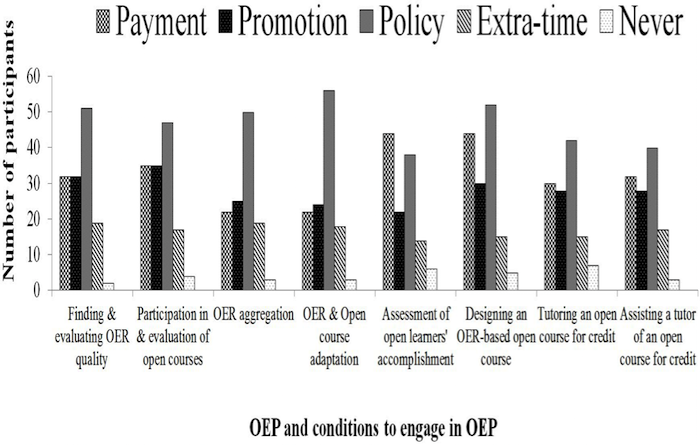

Academics also expressed willingness to engage in different OEPs and conditions under which they would engage in those practices were investigated. The specific OEPs and conditions under which academics would engage in those practices are summarised in Figure 4. The OEPs include 1) finding OER and evaluating their quality, 2) participating in and evaluating an open course, 3) aggregating OER, 4) adapting OER and open courses, and 5) assessing accomplishment from open learning based on OER and open courses for credit.

Figure 4: Conditions for academics to engage in OEPs

The overwhelming majority of participants would engage in these practices if one or more of these four conditions is met: 1) they are paid for it, 2) their practices lead to academic promotion, 3) these practices are supported by a national or an institutional policy, and 4) they have extra time. Academics who said they would never engage in these practices varied between 2.3% who would never find OER and evaluate their quality and 7% who would never assess open learning accomplishment for credit. When it comes to participation in open courses and evaluation of their quality, only 4.7% of participants reported that they would never engage in this practice. As for OER aggregation as well as OER and open course content adaptation, 3.5% reported that they would never participate in these practices.

Overall, policy was found to be the most enabling condition for academics to engage in different OEPs. Exception was on assessment of accomplishment from open learning based on OER and open courses for credit on which payment would be the most important catalyst of academics’ engagement. On this specific OEP, policy was the second most important condition. For all the four remaining OEPs, promotion and payment were either the second or the third most important condition for academics’ engagement after policy.

Figure 4 also indicates academics’ willingness to contribute to open courses and conditions under which they would make this contribution. Similarly, policy was found to be the most important enabler of academics’ potential contribution to open courses. The second and third most important enablers were found to be payment and promotion respectively. Only 5.8% of participants would never design an OER-based course. When it comes to tutoring an open course for credit, only 8.2% of participants reported that they would never engage in this practice. As for assisting a tutor of an open course offered for credit, only 3.5% said they would never engage in this practice.

It is also worth noting academics’ responses to the statement, “I think opening up higher education can be successfully implemented in Rwanda if the Ministry of Education, the University of Rwanda, academics and learners are all involved and develop ownership”. Fifty-two participants (61.1%) strongly agreed with the statement and 17 others (20%) agreed with it. Eight participants (9.4%) expressed neutrality on the statement and only three participants (3.5%) disagreed with it.

Eleven participants commented on the statement and six of them tended to agree on the importance of engaging all stakeholders for successfully opening up higher education. One participant stated that, “Once these stakeholders join their hands, it can happen…”. Another participant highlighted that, “If the mentioned parts [sic] take things serious, it can be successfully implemented”. A third participant went further to stress that the best model would be to involve all stakeholders in related policy design. However, some comments expressed skepticism about the possibility of involving all stakeholders in making opening up higher education run successfully. “The main problem is that decision makers would hardly be committed to this cause”, so stated another participant. Two participants also emphasised giving enough attention to challenges (including financial constraints and resistance to change, mentioned by one of them).

Finally, participants were given an open opportunity to express their ideas or concerns. Many of the responses to this opportunity reiterated the critical role of policy as well as concerns about technological access and quality in open education. Others were optimistic about the potential of open courses for increasing access to higher education. One participant asked to organise a workshop at the university level as soon as possible, so that academics could learn more about open learning and opening up education, while another expressed the desire to be trained in the use of social media to support learning: “I wish I could be educated on how to use the social media programs to support the learning process of my students”. There was also a pessimistic comment:

You ask questions as if you are not Rwandan: With this working motivational environment (little salary, poor equipment and infrastructure, etc) how can you use such social media oriented in academics [sic]? Have you ever seen any lecturer getting a laptop from the institution as it happens to other civil servants in public administration?

Although 71.7% of participants expressed willingness to publish under open licences if the cost barrier is removed and this practice leads to academic promotion, it is worth noting the reason advanced against this practice: “high impact journals are often not open access”. The citation-based impact factor has recently been adopted in deciding academics’ promotions. That is why many of them have been influenced to overestimate the value of the number of citations of their work over the real impact of the work in changing learners and societies.

While citation is important, it is interesting to see that, for some academics at the University of Rwanda, the citation-based impact has tended to be more important than making higher education more accessible and affordable. In 2014/2015, this university was unable to accommodate thousands of learners from low income families who had been admitted on a merit basis but could not secure student loans due to the shortage of funds (Nkuyubwatsi, 2016a, Nkuyubwatsi et al., 2015). Arguably, the inclusion of these thousands of learners enabled by the institutional and individual adoption of OEPs would be much more impactful than thousands of citations. An academic, institution and policy maker who care about socioeconomic inclusion of citizens in their respective countries (and beyond) would support an open licence for academic work to avoid the high cost and the high price of higher education (see Jansen, 2015) and adopt other OEPs.

The citation-based impact factor attracted serious criticism due to the malicious manipulations it triggered: 1) coercing authors to cite articles in the same journal in return for acceptance of their manuscripts (Matthews, 2015), 2) an explicit bias toward experiential sciences over social sciences (Calver & Beattie, 2015), 3) putting the reputation of the author over the quality of the manuscript (Ramaker & Wijkhuijs, 2015; Wijkhuijs, 2015), 4) editorial self-citation and development of citation networks (Hall & Page, 2015), 5) commercialisation of co-authorship (Hvistendahl, 2013), and 6) paying for affiliation with highly cited authors (Haustein & Larivière, 2015).

Policy was found to be the most important condition for academics to contribute to OER and open courses, and engage in other OEPs, followed by payment and promotion. These findings concur with studies that found policy (Butcher, 2011; Wyk, 2012; Conole, 2013), incentives (OECD, 2007; McAndrew, Farrow, Law, & Elliott-Cirigottis, 2012), and salary (Badrach, Kanyazeva, & Lane, 2012) to be among the most important enablers of OER and OEP adoption. In the current study, the potential influence of the national policy was found to be slightly higher than the influence of the institutional policy (72.9% versus 71.6% of participants) and this has a meaning in the Rwandan context: national policies inform institutional policies.

Although 80% of participants supported the idea of making a list of competencies needed for awarding different qualifications publicly available, a concern that such a practice would trigger laziness among learners was expressed. Benson, Anderson, & Ooms (2011) found a similar concern in their study on academics’ perceptions, attitudes and practices towards blended learning in a British university: some academics were concerned about the potential laziness of students if teachers provide resources rather than letting students find the resources themselves. Therefore, the concern of learners’ laziness that may be triggered by open sharing of learning resources is not a particularity of Rwandan academics.

Some academics also raised a concern that opening up higher education would affect the quality of education, because they thought that the infrastructure that exists in Rwanda is inadequate. This concern was also voiced in other settings (Atkins, Brown, & Hammond, 2007; Bateman, Lane, & Moon, 2012.). In some under-resourced settings, however, OER adoption was backed by an agenda to overcome infrastructural challenges (Omollo, Rahman, & Yebuah, 2012). The other concern raised by participants was the lack of academics’ preparedness, which relates to limited competencies (OECD, 2007; Rennie & Mason, 2010; Badrach, Kanyazeva, & Lane, 2012). Equally, the lack of access to technologies by learners that was also highlighted in Lane (2009), Bates (2012), and Liyanagunawardena, Williams, & Adams (2013) was raised among the concerns.

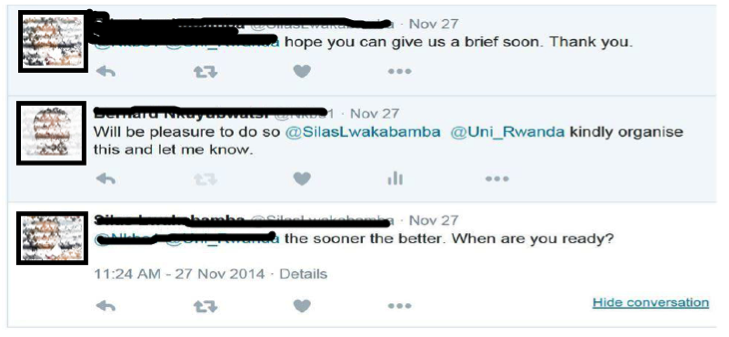

Subsequent to the study, there have been responsive actions: 1) The National Open, Distance and eLearning (ODeL) policy was developed following an open Twitter discussion on opening up higher education the researcher held with the Minister of Education and the latter’ s invitation of the researcher to contribute a policy brief (see Figure 5). Both the discussion on opening up higher education in Rwanda and the subsequent contribution of the policy brief were part of the Parallel development component highlighted in the Methods section. The National ODeL policy was followed by 2) the University of Rwanda’s institutional ODeL policy on which the researcher was invited to review and provide constructive feedback. In the light of the University of Rwanda’s ODeL policy, the researcher led experts who developed 3) a methodology for ODeL capacity building for the University of Rwanda staff and 4) an ODeL strategic plan for the University of Rwanda. These four responsive actions evidence the significance and impact of the study and its transformative design.

Figure 5: The Minister of Education’s invitation to provide a policy brief

Both the methodology for ODeL capacity building and the ODeL strategic plan were developed by ODeL Footprints, a consulting company created by the researcher to support initiatives that may contribute to opening up higher education. The methodology and the strategic plan are responsive to the voice of the University of Rwanda’s academics reflected in the previous sections and to the data collected from other stakeholders. ODeL Footprints recommended that open educational practices (OEPs) that contribute to ODeL expansion: a) are supported in the ODeL strategic plan and the methodology for ODeL capacity building, b) lead to academic promotion, c) are part of academic workload, and d) the staff involved share 60% of income from related open educational services (Nkuyubwatsi, 2016b and 2016c), which may counter the dissatisfaction expressed in one of the comments (the hygiene factor, according to Turabik & Baskan, 2015).

Academics expressed willingness to publish their work under open licences, design OER-based courses, tutor open courses for credit and assist tutors of open courses for credit. Equally, academics expressed willingness to find OER and evaluate their quality, participate in open courses and evaluate their quality, aggregate OER, adapt OER and open courses, and assess accomplishment from open learning for credit. Institutional and national policies were found to be the potentially most important enablers for these practices to occur. The study was followed by responsive actions reflected in the development of: 1) the national ODeL policy, 2) the University of Rwanda’s institutional ODeL policy, 3) a methodology for ODeL capacity building for the University of Rwanda staff and 4) an ODeL strategic plan for the University of Rwanda. OEPs that will be triggered by these responsive actions may enable academics in Rwandan public higher education to develop, deliver and expand ODeL within the framework of transformation of Rwanda into a middle-income, knowledge-based society.

Atkins, D.E., Brown, J.S., & Hammond, A.S. (2007). A review of the open educational resources movement: Achievement, challenges and new opportunities. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from this URL.

Badarch, D., Knyazeva, S., & Lane, A. (2012). Introducing the opportunities and challenges of OER: The case of the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Baltic States. In J. Glennie, K. Harley, N. Butcher, & T.V. Wyk, (Eds.), Open educational resources and changes in higher education: Reflection from practice. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning.

Bateman, P., Lane, A., & Moon, B. (2012). Out of Africa: A typology for analysing Open Educational Resources initiatives. Journal of Interactive Media in Education. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-11/

Bates, T. (2012, August 5). What’s right and what’s wrong about Coursera-style MOOCs. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://www.tonybates.ca/2012/08/05/whats-right-and-whats-wrong-about-coursera-style-moocs/

Benson, V., Anderson, D., & Ooms, A. (2011). Educators’ perceptions, attitudes and practices: Blended learning in business and management education. Research in Learning Technology, 19 (2), 143-154. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://www.researchinlearningtechnology.net/index.php/rlt/article/view/10353/11979

Bijsterveld, C., & Dopper, S. (2012). Integrating open educational resources into the curriculum. In R. Jacobi, & V.D.N. Woert (Eds.), Trend report: Open educational resources 2012 (pp. 17-24). Retrieved January 13, 2017, from https://www.surfspace.nl/media/bijlagen/artikel-697-ee18ac0f1441bb158e6122818f5f589e.pdf

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butcher, N. (2011). A basic guide to Open Educational Resources (OER). Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002158/215804e.pdf

Calver, M., & Beattie, A. (2015, May 31). Our observation with metrics is corrupting science. The conversation. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://theconversation.com/our-obsession-with-metrics-is-corrupting-science-39378

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). Oxford: Routledge.

Conole, G. (2013). Designing for learning in an open world. New York: Springer.

David, M., & Sutton, D.C. (2011). Social research: An introduction (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Dennis, B. (2009). Theory of the margins: Liberating research in education. In R. Winkle-Wagner, A.C., Hunter, & H.D. Ortloff (Eds.), Bridging the gap between theory and practice in educational research: Methods at the margins. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 63-75.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The good research guide for small-scale social research projects (4th ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.

Ehlers, U. (2011). From Open Educational Resources to Open Educational Practices. eLearning Papers (21). Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.oerup.eu/fileadmin/_oerup/dokumente/media25161__2_.pdf

Geser, G. (2007). Open educational practices and resources: OLCOS roadmap 2012. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://www.olcos.org/cms/upload/docs/olcos_roadmap.pdf

Hall, C.M., & Page, S.J. (2015). Following the impact factor: Utilitarianism or academic compliance?. Tourism Management, 51. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261517715001089

Haustein, S., & Larivière, V. (2015). The use of bibliometrics for assessing research: Possibilities, limitations and adverse effects. In M.I. Welpe, J. Wollersheim, S. Ringelhan, & M. Osterloh (Eds.), Incentives and performance: Governance of research organizations. New York: Springer.

Hvistendahl, M. (2013). China’s publication bazaar, Science 342 (6162), 1035-1039. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from https://www.sciencemag.org/content/342/6162/1035.full

International Council for Open and Distance Education. (n.d.). Definition of open educational practices. Retrieved November 26, 2015, from http://www.icde.org/en/resources/open_educational_practices/definition_of_open_educational_practices/

Jansen, J. (2015, October 15). UFS responds to concerns around high costs of higher education. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://www.ufs.ac.za/template/news-archive-item?news=6526

Kincheloe, L.J., & McLaren, P. (2005). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In K.N. Denzin, & S.Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publishing Inc.

Lane, A. (2009). The impact of openness on bridging educational digital divides. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 10. Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://oro.open.ac.uk/24791/1/IRRODL_2009.pdf

Lane, A. (2010). Global trends in the development and use of open educational resources to reform educational practices. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://iite.unesco.org/pics/publications/en/files/3214676.pdf

Liyanagunawardena, T., Williams, S., & Adams, A. (2013). The impact and reach of MOOCs: A developing countries’ perspective. eLearning Papers (33). Retrieved January 22, 2017, from http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/32452/

Matthews, D. (2015, November 5). Lost credibility. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved November 23, 2017, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/11/05/editorial-says-journal-impact-factors-have-lost-credibility?utm_content=buffer0162a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook&utm_campaign=IHEbuffer

McAndrew, P., Farrow, R., Law, P., & Elliott-Cirigottis, G. (2012). Learning the lesson of openness. Journal of Interactive Media in Education. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-10/

Nkuyubwatsi, B. (2016a). A critical look at the policy environment for opening up public higher education in Rwanda. The Journal of Learning for Development, 3(2), 47-61. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from http://www.jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/141

Nkuyubwatsi, B. (2016b). The outcome of constructive alignment between open educational services and learners' needs, employability and capabilities development: Heutagogy and transformative migration among underprivileged learners in Rwanda. Cogent Education, 3(1). DOI:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1198522. Retrieved October 10, 2017, from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2016.1198522

Nkuyubwatsi, B. (2016c). Positioning extension Massive Open Online Courses (xMOOCs) within the Open Access and the lifelong learning agendas in a developing setting. The Journal of Learning for Development, 3(1), 14-36. Retrieved April 17, 2016, from http://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d

Nkuyubwatsi, B., Ndayishimiye, V., Ntirenganya, B.J., & Umwungerimwiza, D.Y. (2015). Towards innovation in digital and open scholarship for non-rivalrous lifelong learning and supporting Open Learning: The case of the Open Scholars Network. eLearning Papers (44), 53-59. Retrieved April 17, 2016, from http://openeducationeuropa.eu/en/paper/teacher-s-role-educationalinnovation

OECD. (2007). Giving knowledge for free: The emergence of open educational resources. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.oecd.org/edu/ceri/38654317.pdf

Omollo, K.L., Rahman, A., & Yebuah, C.A. (2012). Producing OER from scratch: The case of Health Sciences at the University of Ghana and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. In J. Glennie, K. Harley, N. Butcher, & T.V. Wyk (Eds.), Open educational resources and changes in higher education: Reflection from practice. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning. pp. 57-73.

Ramaker, R., & Wijkhuijs, J. (2015, January 29). The fight for open access. Univers. Retrieved January 26, 2017, from https://universonline.nl/2015/01/29/the-fight-for-open-access

Rennie, F., & Mason, R. (2010). Designing higher education courses using Open Educational Resources. In M.S. Khine, & I.M. Saleh (Eds.), New science of learning: Cognition, computers and collaboration in education. New York: Springer. pp. 273-282.

Seale, C. (2012). Sampling. In Seale, C. (Ed), Researching society and culture (3rd ed.). London: Sage, pp. 134-152.

Taiwo, A.A., & Downe, G.L. (2013). The Theory of User Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): A Meta-analytic review of empirical findings. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 49(1). Retrieved October 3, 2017, from http://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol49No1/7Vol49No1.pdf

Turabik, T., & Baskan, A.G. (2015). The importance of motivation theories in terms of education systems. 5th World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership, WCLTA 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2017 from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042815022661

Weller, M. (2014). The battle for open: How openness won and why it doesn’t feel like victory, London: Ubiquity Press. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from http://www.ubiquitypress.com/site/books/detail/11/battle-for-open/

Whiteman, N. (2012). Undoing ethics: Rethinking practice in online research. New York: Springer.

Wijkhuijs, J. (2015, July 2). Dutch universities start their Elsevier boycott plan. Univers. Retrieved January 24, 2017, from https://universonline.nl/2015/07/02/dutch-universities-start-their-elsevier-boycott-plan

Wolfenden, F. (2012). OER production and adaptation through networking across Sub-Saharan Africa: Learning from TESSA. In J. Glennie, K. Harley, N. Butcher, & T.V. Wyk (Eds.), Open educational resources and changes in higher education: Reflection from practice. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning. pp. 91-105.

Wolfenden, F., Buckler, A., & Keraro, F. (2012). OER Adaptation and reuse across cultural contexts in Sub Saharan Africa: Lessons from TESSA (Teacher Education in Sub Saharan Africa). Journal of Interactive Media in Education. Retrieved January 23, 2017, from http://www-jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2012-03/

Wyk, T.V. (2012). Taking OER beyond the OER Community: Policy issues and priority. In J. Glennie, K. Harley, N. Butcher, & T.V. Wyk (Eds.), Open educational resources and changes in higher education: Reflection from practice. Vancouver: Commonwealth of Learning. pp. 13-25.

Author:

Bernard Nkuyubwatsi is a Research Professor of ODeL and Learning Innovation at EUCLID University and the founder of ODeL Footprints. He holds a PhD in Education/eLearning and Learning Technologies from the University of Leicester and an MA in Online and Distance Education from the UK Open University. His research interests include ODeL, MOOCs, OER, and transformative research. Email: nkuyubwatsi1[@]gmail.com