2024 VOL. 11, No. 2

Abstract: This paper presents a conceptual model which explains the challenges of providing high quality sustainable, teacher professional development at scale. It provides a framework to support holistic thinking at a systemic level, applicable across different systems.It draws on sociocultural theories of learning and encourages the user to think about the knowledge and skills required by actors at different levels of the system and the structures required to support their learning. It brings together the needs of teachers, school leaders and Education Officers (at the County, District or Provincial level). The empirical evidence for this model comes from a seven-year programme of activity supporting school-based professional development in Zambia. Evaluation findings highlight the importance of the role of mid-level professionals (District and Provincial Officers) in ensuring the sustainability of gains made through development projects. This is important because the professional development needs of those supporting teachers are often neglected.

Keywords: teacher professional development, sustainable change, ZEST, education systems

Traditionally, teacher professional development takes place away from school, during school breaks, and employs a cascade model in which ‘master trainers’ pass on information that policy makers believe teachers need. The work of the Teacher Professional Development @Scale coalition highlights the pillars of effective TPD provision (Boateng & Wolfenden, 2022; Wolfenden, 2022) and is driving a shift towards school-based models which encourage collaboration in context. For example, in Kenya (in 2021), the Teaching Services Commission launched a TPD programme, which requires teachers to meet and discuss practice in school (Mabele et al., 2023), and in Ghana teachers are encouraged to form ‘professional learning communities’ in which to discuss and develop practice. Educational outcomes remain stubbornly low across Sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Bold et al., 2017), but sustainable improvement requires new classroom practices or behaviours, from teachers (Fullan, 2007; Stutchbury & Biard, 2023; Wedell, 2009), and this is difficult to achieve. The focus on new models for TPD in which the training is school-based, collaborative and related to context is welcome.

In Zambia, unusually, school-based continuing professional development (SBCPD) has been part of education policy since 1998, when a version of the Japanese ‘lesson study’ was adopted (Jung et al., 2016; Seleznyov et al., 2024). All teachers are required to attend regular ‘teacher group meetings’ (TGMs) and the Ministry of Education has achieved universal coverage by mandating a prescribed formula that all schools are expected to follow and creating a system through which it is monitored..

Zambia has ten provinces, each divided into districts. Each district is divided into zones, with schools receiving support from zonal in-service coordinators. Schools and zones are monitored by District Education Standards Officers (DESOs) and supported by District Resource Centre Coordinators (DRCCs). These mid-level professionals monitor the implementation of SBCPD; they exercise considerable power and influence but, in some places, their activities are limited through a lack of resources.

In primary schools, the system has not yielded improvements in teaching and learning (Baba & Nakai, 2009; Phiri, 2020; Seleznyov et al., 2024), and our own research suggests that it is not popular amongst primary school teachers. The rigid ‘one size fits all’ model alongside a lack of resources that bring in new ideas, mean that schools and teachers are not empowered to adapt the scheme to meet local needs.

The Zambia Education School-based Training (ZEST) started in 2017, with the aim of introducing adaptations to Lesson Study that addressed some of the challenges. It was originally intended to run until 2022. However, two extensions from the funders have provided the opportunity to focus on sustainability. An endline evaluation was completed in November 2022 but with funding until 2024, we have been able to engage proactively with stakeholders to discuss sustainability and to work with small groups of teachers to better understand how school-based continuing professional development (SBCPD) is experienced. A key contribution from this extended engagement in the setting is a more holistic understanding of layered educational systems that goes beyond a focus on teachers to highlight the role of mid-level professionals in ensuring sustainability.

In this paper, we use our research from the implementation of ZEST to develop a conceptual model which could be applied to any TPD programme operating at scale. It has a strong theoretical underpinning and highlights the questions that need to be addressed for the context concerned.

School-based teacher development programmes are underpinned by the belief that knowledge about teaching is socially constructed in a particular cultural context, and that learning to teach involves practising new teaching approaches, collaboration, and reflection (Kelly, 2006; Putnam & Borko, 2000). Teachers need access to contextualised resources to provide a focus for discussion and help them to make meaning of new pedagogies and develop new classroom strategies.

The Zambian Ministry of Education Strategic Plan (HEA & Management Development Division, Cabinet Office, 2022) states its ambition to “enhance capacity development of teachers, college lecturers on classroom level, practical, and learner-centred pedagogical practices” (p. 34). Much pre-service and in-service teacher education is based on a view that knowledge about teaching is like knowledge about physics — objective, fixed, unproblematic (Stutchbury, 2019). The result is a system which values exam-based qualifications and leaves teachers ill-equipped to cope with the demands of classroom teaching. In this paper we argue that understanding the implications of learner-centred pedagogy requires a different view of knowledge about teaching — one that is more flexible, nuanced, generated in communities in context — and highlights the role of professionals at all levels in the system in bringing about change. ZEST contributes to the operationalisation of the Ministry’s strategic aim by seeking to change the narrative and develop new knowledge of teaching in communities.

The Endline Evaluation Report (Stutchbury, Gallastegi et al., 2023) sets out the achievements of ZEST; this paper draws on project data and theory to draw out learning that could be applied to any large scale TPD programme operating in a multi-layered system. This higher-level analysis contributes to our understanding of the issue of ‘sustainability’ and highlights the parts of the system which need attention if this is to be achieved. We start by providing a summary of ZEST — what we did and why we did it that way. Drawing on our experiences, we set out a socio-cultural learning theory which provides an analytical framework through which to consider issues of sustainability. We will conclude with suggestions for further research and insights that are informing new research.

ZEST has been implemented in Central Province in Zambia and has reached over 4000 teachers in 500 primary schools. Three cohorts of 200 teachers were involved in a co-design process, with a scale-up to 4000 teachers (Cohorts Four and Five) in years four and five. It is an SBCPD program offering small, but important and manageable modifications, to the Lesson Study cycle (Jung et al., 2016). ZEST incorporates the features of successful TPD: access to new ideas, opportunities for professional experimentation, focused collaboration, access to expert support, and the use of technology (Wolfenden, 2022).The innovative use of technology has made resources to support pedagogic change available to teachers on their mobile phones. Each school was provided with a Raspberry Pi computer (small, low power, inexpensive) which was wifi-enabled and acted as a server. Teachers in schools that had no electricity were able to access digital resources in this way through the use of a solar charger (Gaved et al., 2020; Stutchbury et al., 2019; Woodward et al., 2022).

In Lesson Study, teachers identify a ‘problem’ and work as a group to plan a lesson designed to tackle that problem (e.g., What is the best way to teach fractions?). A volunteer teaches a ‘demonstration’ lesson with the others watching. After the lesson, it is critiqued, re-planned and re-taught — the aim being to produce a lesson that others could copy. In ZEST, the random selection of a topic is replaced by a progressive programme of learning. In year one, for example, this focused on nine active teaching approaches. During a TGM teachers discuss an approach (e.g., using pair work), supported by resources, including audio and video assets recorded in Zambia. They each plan a short classroom activity to try out in the following few days. They re-convene to reflect together on how it went and plan another activity using the same approach. By the end of the year, they are linking the activities to create engaging lessons.

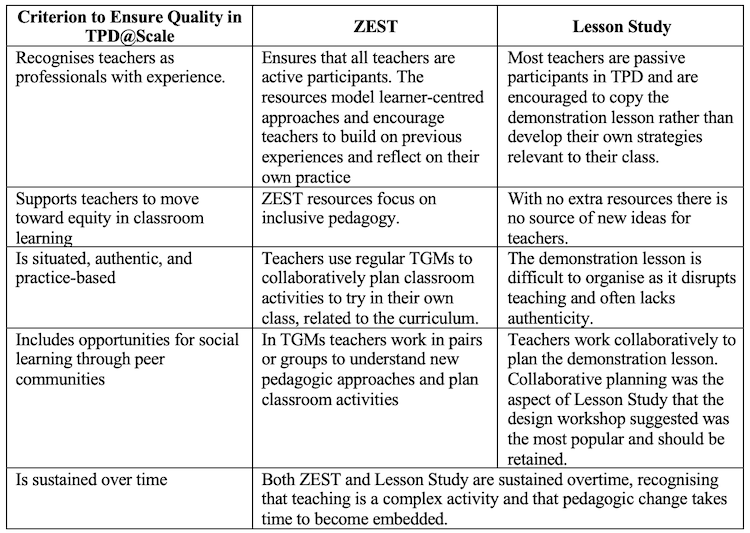

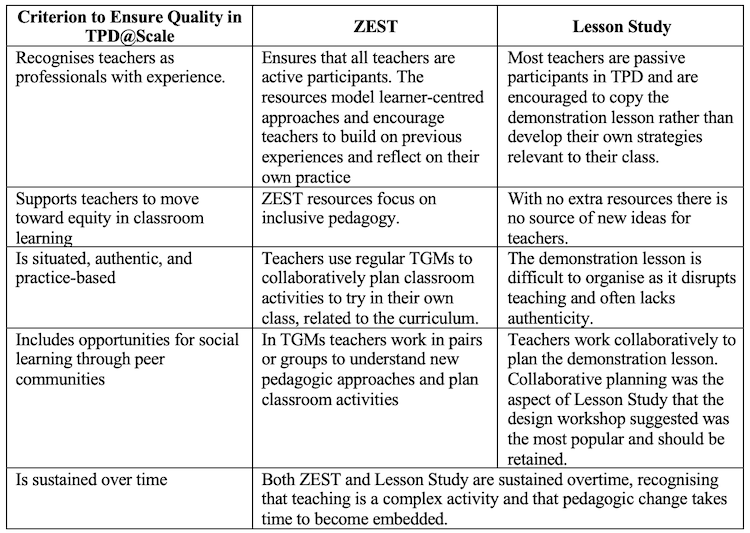

The ZEST program incorporates the elements that have been identified as being important in quality teacher professional development (Wolfenden, 2022), and, in this respect, it improves on Lesson Study (Table 1).

Table 1: A comparison of ZEST and Lesson Study

Implementation of ZEST has been guided by four key concepts: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring (May & Finch, 2009; Stutchbury & Biard, 2023).

Coherence asks implementers to analyse the current situation and to make explicit how the intervention fits into the relevant situation. Crucially, ZEST uses established structures, roles and processes and introduces three small but important changes: a progressive set of problems to be discussed, the replacement of the demonstration lesson by the expectation that all teachers will plan and try out an activity in their classroom that uses the ideas discussed in the TGM, and the use of reflection and informal peer observation to evaluate teaching.

There is ‘coherence’ between ZEST and Lesson Study in terms of their ultimate aims — to improve the quality of teaching. Achieving ‘coherence’ of the underlying philosophy of learning and teaching has been more challenging. Lesson Study is predicated on the view that there is a ‘right way’ to teach certain topics and the stated policy that teaching should be more ‘learner-centred’ is not widely understood. In the design phase of ZEST, we surfaced misconceptions about learner-centred education that should be challenged. The ZEST resources use Schweisfurth’s ‘minimum criteria’ (Schweisfurth, 2015) as a definition for ‘learner-centreness’ and, in introducing ZEST, the notions of ‘fixed intelligence’ and that learners are ‘empty vessels’ waiting to be ‘filled up’ by their teachers, have been gently challenged.

May and Finch (2009), suggest that successful implementation requires intellectual ‘buy-in’ to the ideas that underpin the intervention or change (cognitive participation) by the key actors, and meaningful collective action to bring about change. In our experience there is a dialectic relationship between cognitive participation and collective action. Sometimes teachers or district officials are secure in their understanding of learner-centredness and are excited about planning and taking part in ‘collective action’. More often, ‘collective action’ to bring about small changes in practice (such as asking a few open questions, moving about the room, or organising pair work) elicits new responses from learners, which, over time, changes attitudes towards and in learners and brings about new understandings of the complexity of teaching (Murphy & Wolfenden, 2013). In ZEST, the resources for teachers support ‘collective action’ by providing activities for teachers to do together in TGMs, make explicit the minimum criteria for learner-centredness, and operationalise a view of teacher learning in which knowledge is socially constructed in a particular cultural context. A critique of ZEST that has emerged through the analysis described here is that the ‘collective action’ required by those tasked with supporting teachers (District and Provincial Officers) is less clear.

Reflexive monitoring is an ongoing process in which implementers are encouraged to continually review and evaluate the assumptions that underpin chosen actions and make changes to the implementation process if necessary. In ZEST, this process resulted in the introduction of the Raspberry Pi computers for Cohort Three, the re-conceptualisation of ZEST from a one-year programme of activity to two years, a change to the way in which teacher notebooks were introduced, and, crucially, the realisation of the importance of the role of the district and provincial officials. We observed that the relationships between these groups and teachers did not always model the way in which teachers were expected to relate to children (Stutchbury et al., 2019). Often, teachers are blamed for the lack of implementation of aspirational policies, whereas, the reality is that they lead complex lives, often facing numerous basic challenges (Tao, 2013). On occasions we have observed a lack of curiosity amongst mid-level professionals towards teachers. For example, instead of asking head teachers why they are struggling to hold the requisite number of TGMs in a term, they will restate the policy that they should take place every two weeks. The assumption is that the head teacher is disregarding the policy, whereas the reality is that schools are often under pressure owing to staff illness, local weather conditions, or the requirement to implement a new initiative. A significant error made in Cohort One was to produce a ‘teachers handbook’. The same resources were re-labelled in Cohort Two as a ‘Training Guide’, because we realised that those whose role it was to support teachers, did not think the ‘Teacher’s Handbook’ was relevant to them. One of the key strengths of ZEST is the fact that the knowledge which underpins the intervention is made available to everyone at all levels of the system. This is an equity issue, and the Implementation Guide (co-designed with District and Provincial Officers) is also available to teachers and school leaders. In many interventions it is ‘master trainers’ who receive resources, which they use to prepare formal presentations for teachers, often away from school, in which they are expected to absorb new ideas. As we will demonstrate in the next section, although teacher agency and autonomy are important (and this is what we have sought to support in ZEST), their work is situated within a complex, fluid, layered system. Understanding the relationships within and between the layers is important in achieving equity and sustainability.

Before we do this however, it is worth summarising the main achievements of ZEST and highlighting the challenges that it has revealed. An endline study in which 56 schools were visited, and 160 lessons observed, showed that the median proportion of time in a lesson for which learners were actively engaged increased from 5% to 15% (Stutchbury, Gallastegi et al., 2023); 15% of a 40-minute lesson is six minutes, which we judge to be long enough for a meaningful pair work activity or a set of open questions to be asked and discussed. If every lesson in a day included such an activity, school would begin to ‘feel’ different for learners. There was also a significant increase in the number of lessons for which this proportion was 20% or 30%. The average number of TGMs per school year increased from 9 to 11, and qualitative evidence suggested that relationships in school have improved, and TGMs are better attended, more purposeful and support meaningful collaboration. We received reports that learner attendance and learner achievement have improved, and that teachers are more confident in their use of IT.

However, the ‘median’ hides the fact that in some localities engagement is still poor. Groups of teachers — particularly in places where multiple shift systems operate owing to the large number of school-aged children in an area — remain marginalised. Although the cost of sustainability is relatively low (the cost of a Raspberry Pi computer per school) and the resources are free, with an open license, a political commitment from central government is still required. District and Provincial Officers in Central Province have the experience to train others (without NGO support), but to be effective new attitudes towards teachers need to be modelled and the knowledge base amongst this professional group needs to be developed. A crucial component of teachers’ knowledge is pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) (Shulman, 1986). This is largely absent from pre-service teacher training courses in Africa (Akyeampong et al., 2012; Dembele & Miaro-II, 2013; Westbrook et al., 2014) yet effective teachers will develop PCK as part of their tacit ‘knowledge in practice’ as they observe learners and make decisions about their teaching. There are opportunities for district and provincial officials to develop PCK as they visit schools, observe practice in different settings, and discuss their observations. It is not clear however, that mechanisms for this learning exist. As we will argue below, this matters as they are being asked to support teachers in implementing new practices, which they have often not experienced or used. In a multi-layered, education system actors at all levels of the system have things to learn. By analysing ZEST from different perspectives, we have developed new understandings of the relationships between the layers that could apply to any such system.

It has been suggested that teacher professional development programmes should be positioned within a framework that supports both teacher learning and pupil learning (Soler & Fletcher-Campbell, 2022). We will argue that for sustainability, ‘learning’ should extend to those tasked with monitoring and supporting teachers (District and Provincial Officers), and those with oversight of schools and the curriculum at the Ministry level. Policy makers need to create the conditions for learning and understand that when a TPD programme is introduced, learning will need to take place at all levels of the system. What is learnt and how it is learnt will be different for different actors. In ZEST, the intention was to bring about change ‘from the bottom up’ (Elmore, 1980), with the main effort focused on the point where the change is most needed (the classroom). But the experience of working in the system for seven years and the findings from both quantitative and qualitative research have highlighted the importance of a more holistic view, in which relationships within and across the layers of the system are strengthened. If a programme is to be introduced that is efficient and cost effective, it needs to reach all teachers — it needs to be equitable, recognising that different groups of teachers work in different settings and contexts and will have different needs. Teachers need support from people with skills in mentoring and coaching and the humility to learn themselves. New understandings of culturally appropriate active pedagogies need to be constructed across the system through dialogue, reflection, and practise.

Building on the conceptualisation of knowledge about teaching as being socially constructed in a particular cultural context, ‘learning’ can perhaps be considered in terms of people’s changing participation in the socio-cultural activities of their communities (Vygotsky, 1978). Rogoff (2008) proposes three mutually constituted planes of analysis which co-exist spatially and temporally. This can help to explain the nature of learning in communities, suggesting that we need to consider personal (individual), interpersonal, and community processes. These planes are interconnected and for TPD to be effective and sustainable, attention needs to be paid to each plane. Drawing on these planes, Soler and Fletcher-Campbell (2022), provide criteria that highlight the conditions that should be in place to support professional learning and equitable practice at each level of the system. In their analysis they equate the planes of analysis with the levels of the system. In the analysis that follows, we take a more processual approach, using the planes to analyse the mechanisms that are required to support learning at different levels of the system. We draw on project data to critically review the extent to which ZEST supports system-wide reform, to identify the key challenges that remain, and show how these may be addressed to ensure sustainability.

Rogoff (2008) suggests that the unit of analysis for understanding learning is the ‘activity’ or ‘event’ undertaken by individuals and their social partners (colleagues) in their cultural setting. She argues that the individual and the social setting are mutually involved, that they don’t exist separately and “it is incomplete to assume that development occurs in one plane and not in others” (p. 141). Development (or learning) takes place at three levels: the individual, the interpersonal, and the community. From a socio-cultural perspective, teachers and district and provincial officials are part of a mutually constituted whole, all engaged in the ‘activity’ of ‘education’ in a specific environment. Their actions are interdependent and a change in the ‘activity’ of ‘teaching’ in one part of the community (schools) will impact other communities (District and Provincial Officers). Where that change involves new ideas and new practices, people need to work together (guided participation) to achieve ‘participatory appropriation’. ‘Participatory appropriation’ is “the personal process by which through engagement in an activity, individuals change and handle a later situation in ways prepared by their participation in the previous situation” (p. 142). In other words, people learn to act differently. Using this model, learning is seen as “a process of becoming rather than acquisition” (p. 142). We will now apply this lens to the actors at the different levels of the education system. We suggest that insufficient attention has been paid to what and how mid-level professionals need to learn so that they can exercise the power they possess in supporting sustainable change. For each group, it makes sense to think about what it is they need to learn (the professional knowledge associated with their role) before considering the mechanisms required to support their movement from ‘novice’ to ‘participatory appropriation’ (new practices embedded).

In ZEST the focus has been on teachers. Teachers need good subject knowledge, knowledge of the ideas underpinning educational policy (in the case of Zambia this is learner-centred education), knowledge of inclusive pedagogy, and knowledge of their class. We realised in the design phase of ZEST that TGMs are critical. The ZEST resources exemplify possibilities for inclusive classroom practice and encourage a pedagogy for the meeting which mirrors that expected in the classroom — active participation by all, time for discussion, previous knowledge, and experience is valued. Over time, ‘guided participation’, in which those that are developing confidence support others, becomes ‘participatory appropriation’ (where new practices are ‘owned’ and embedded). Relationships between teachers and between teachers and learners become more respectful as teachers begin to recognise that they are learning from and about their learners rather than ‘filling them up’ with knowledge. This shift from the individual to community learning is supported by the materials. The materials are presented in the form of six ‘courses’ (with a quiz at the end of each one) and we suggest that these be studied over two years. Each teacher registers on the Moodle system and when they have completed all the pages and achieved a certain level in the quiz, a certificate is generated. These certificates have been appropriated in some areas as evidence of individual achievement and provide credit towards re-licensing. The ‘quiz’ is not a conventional test. It can be done several times and the idea is that it will be discussed as part of the joint meaning-making process. What matters is not the individual responses but the shared understanding of teaching in context generated through the activity. In terms of teacher learning, therefore, we would argue that ZEST has put in place the mechanisms that support a deepening of pedagogical knowledge within context — a process of ‘becoming’ rather than simply acquiring knowledge.

Implementing changes to SBCPD has implications for school leaders. School leaders need knowledge and understanding of the ideas underpinning educational policy and the ability to recognise how these manifest themselves in the classroom, alongside knowledge of their teachers, their development needs, and knowledge of the community which the school serves. They also need knowledge and skills in instructional leadership and the humility to recognise that they are not necessarily expert in classroom teaching as, in many cases, it is an activity that they no longer participate in. They have access to the training materials and evidence from research carried out in one district (Stutchbury, Woodward et al., 2023) suggests that effective head teachers take part in TGMs — not as facilitators but as participants, recognising that they need to understand and be part of the conversation about what LCE entails in their context. What is less clear from our work in ZEST is what opportunities there are for school leaders to meet as a peer group and whether they have opportunities to share experiences of good practice to develop their own understanding of how to recognise learner-centredness.

Policy on TPD is set by the Ministry of Education and disseminated to Provincial and District Officers who are responsible for ensuring its implementation. To be effective, this professional group need knowledge and understanding of the ideas that underpin the policy. They also need to model the attitudes and values that it represents in their relationships with schools and teachers and be able to recognise learner-centred teaching. They need skills in instructional leadership and enough pedagogical knowledge and wisdom to be able to gain the trust of teachers. Many teachers in Africa attend professional development sessions, at a central location, which consist of formal lectures urging them to adopt active teaching strategies (e.g., O’Sullivan, 2010). It is well-known that in teacher education ‘the medium is the message’ — teachers and student teachers are more likely to be learner-centred if they have experienced learner-centred attitudes, values, and approaches as part of their training. Experience in ZEST suggests that for this professional group mechanisms to move from personal learning to ‘participatory appropriation’ are limited.

Evidence for this came from Cohort Two of the project. In Cohort Two, ZEST was introduced into an urban district. We observed that District and Provincial Officers were much more involved in schools than in rural areas, where fuel shortages and a lack of transport make it difficult for them to carry out their role. We found that only 29% of teachers were using the notebook that we supplied. The aim was to encourage them to make notes and reflections during TGMs when they were collaboratively planning classroom activities. Researchers were surprised that one of the most frequent questions that we were asked was, ‘What do I write in my notebook?’. The answer, ‘Whatever is useful to you.’ was unhelpful. In some schools the books were being taken in and stamped by district officials and we found evidence of teachers copying text from the resources into their notebook, rather than noting down their own ideas. At the heart of the issue was a lack of understanding at the district level of the changes implied in a shift to a more learner-centred mind-set. The fact that the relationship between Education Officers and teachers is hierarchical, with the former considering themselves to be the ‘experts’ and teachers expecting to be told by them what to do, was also unhelpful. The reality is that just like teachers and school leaders, District Officers need opportunities and mechanisms through which to learn how to adapt their role to make it consistent with the policy they are implementing, especially when the policy is asking them to think differently about learning and learners.

Many Education Officers and ministry officials in Zambia are former teachers. But their training and experience came before the widespread uptake of ideas about active learning and learner-centredness, so they are being asked to implement something of which they have limited experience. For this reason, the ‘training handbook’ is important because it gives actors at all levels of the system access to an account of how learner-centred education can work in practice. But that is not enough — it needs to be contextualised and the ideas adapted for different school-contexts. Education Officers (in theory) have the opportunity to visit different schools and observe different practices. But they will be only ever peripheral members of the communities of practice that exist in schools. What is not clear so far from our work in ZEST is what mechanisms exist at the district, provincial and national levels for actors to develop their knowledge in the interpersonal and community planes.

In the next section we draw these ideas together to present a model to structure thinking about implementing TPD@Scale, and use the model to review the sustainability and prospects for a more equitable system that meets the needs of all teachers.

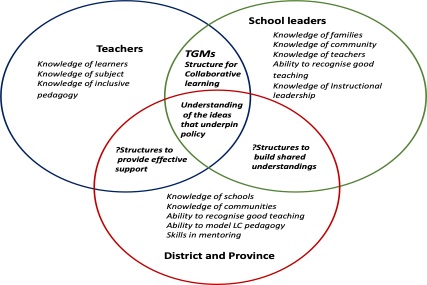

A popular model in this field draws on ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) and represents education systems as concentric circles with the teacher or learners at the centre and the different layers of the ecosystem around them. This is a useful reminder that teachers do not work in isolation, and that it is the support they receive that is crucial. However, Rogoff (2008) suggests that this representation does not take full account of the interaction between individuals and their cultural setting. Drawing on our experience of ZEST we have found it helpful to conceptualise the education system as a Venn diagram with distinct ‘communities of practice’ which overlap. By focussing on what the ‘overlaps’ represent we can identify how better quality and equity could be sustained in the current system. This model (Figure 1) could apply to any multi-layered education system.

At the heart of any educational initiative is a set of ideas about knowledge, learning, and learners. Scott (2010), in his analysis of social structure calls these the ‘discursive’ structures. He argues that when groups of people take action in a social setting, the actions they take will have a theoretical rationale. If this is widely understood (cognitive participation) then implementation is more likely to be successful. In the English education system those ideas are based on cognitive science; in Kenya, the competency-based curriculum is underpinned by Vygotsky and ideas about learner-centred-education; and in Singapore ‘mastery’ is a core concept. These ideas need to be made explicit by policy makers and modelled by those implementing the initiatives. In Zambia, the ideas are based on learner-centred education; they are made explicit and modelled through the ZEST materials. In the Implementation Guide, the first responsibility for all the roles at the district and provincial level, for example, is to familiarise themselves with the resources so they can support schools and teachers appropriately.

The TGMs are a crucial mechanism through which teachers and school leaders move from what Rogoff describes as ‘novice’ to ‘participatory appropriation’ — where the new practices have become embedded and relationships have become more equitable and respectful. This (the overlap between the teachers and the school) has been the focus of ZEST. We provided a facilitator guide and ensured that all teachers could access the materials on their mobile phone through the provision of the Raspberry Pi computer. Our data confirms that TGMs are important but that the quality of those meetings remains variable (Kalaluka, 2024, in preparation).

District and Provincial Officers can and do engage in individual learning by reading books and taking courses. More is required however, to make meaning of their learning in context. We need to understand more about what happens in the overlaps between the district and province with the other groups (indicated by ‘?’). What activities (if any) are undertaken between schools and in district and provincial offices to enable these actors to learn? Do they have ‘district group meetings (DGMs)’, for example. This was put to a group of District Officers in a capacity building workshop and consideration of this will form a part of new research. We know that through slight changes in practice (participation) teachers elicit new responses from learners, which, in turn, bring about further change and, eventually, new attitudes to and in learners (Murphy & Wolfenden, 2013; Stutchbury & Biard, 2023). But what is the equivalent mechanism for actors at different levels — especially those who are not school-based? We argue in the final section that achieving quality and sustainability depends on being able to explore the answer to this question to understand the mechanisms through which mid-level education professionals achieve ‘particpatory appropriation’ with respect to teaching — an activity in which they are not directly engaged. Our data suggests that, at present, these overlaps are characterised by a monitoring mindset. For sustainability we are arguing that a more dialogic relationship is needed based on mutual respect and a willingness to learn. New structures are needed to enable deep learning to take place.

The embedding of Lesson Study throughout Zambia has been achieved through a clear top-down directive and associated checking mechanisms, alongside a set of clear instructions about what teachers are expected to do. In a hierarchical culture this can work. The problem is that the system is not delivering ‘quality’ and schools and teachers do not feel empowered to adapt the system to meet their needs. In ZEST we have demonstrated the strength of the systems, roles and processes in place and introduced small changes so that the system meets the criteria for quality in TPD@Scale (Wolfenden, 2022). The Endline Evaluation provided evidence of success but also highlighted significant challenges to quality. For example, teachers often face multiple initiatives that may overlap and contradict. They need strategies and support in selecting how best to tackle the issues they face, and the flexibility to adapt what is being suggested by policy makers; and the needs of teachers in remote and marginalised communities are not understood. New research is being carried out in a research project that is part of the Empowering Teachers Initiative (FIT-ED, 2023) to better understand how SBCPD can be further adapted in Zambia to meet the diverse needs of teachers. This conceptual framework will inform the questions we ask about the roles of mid-level Education Officers.

But are the changes made through ZEST sustainable? The analysis above suggests that there are three pillars for sustainability: resources, access, and support. The resources provided are open access and, therefore, freely available for download, adaptation, and copying. They are approved in Zambia by the Curriculum Development Centre.

Access is online or via Raspberry Pi computers (offline servers). To implement ZEST, schools need access to the internet (data bundles for teachers’ phones) or a Raspberry Pi computer. It is possible that this low-cost device could be bought by schools with contributions from the local community, church groups, or other charitable organisations. They would need a grant of around $100 to buy the Raspberry Pi, SD (Secure Digital) card and a solar charger.

The analysis above shows that the question of support is more challenging. Mechanisms are needed to support deep learning for those who are not classroom-based but who exercise power and influence within the system. District and Provincial Officers have access to the resources (individual learning) and opportunities for interpersonal learning. How they might interact effectively with each other, teachers, and school leaders is much less clear. A recent emphasis on mentoring is encouraging but needs to move beyond compliance and be conceptualised as a mutually developmental professional conversation. New working practices at the district and province level are required, such as regular learning circles, opportunities to share experiences, and on-going reflection and analysis about what they are seeing in schools, to make meaning in the context of their individual learning. What constitutes ‘collective action’ for those not directly involved in teaching, and what structures are needed is not clear. We need a better understanding of the knowledge base required by mid-level professionals and the structures available to secure ‘participatory appropriation’ with respect to LCE, and to understand how they can support teachers more effectively, ensuring changes are more likely to become embedded.

Although developed in Zambia, we believe that this way of thinking about TPD@Scale has wide applicability. It draws on well-established social theories of learning and implementation (Rogoff, 2008; Scott, 2010; Stutchbury & Biard, 2023) and is set in an educational system that is similar to many other African countries. We would also suggest that it builds on the work of researching improving systems of education (Pritchett, 2015) because it takes account of all the structural factors highlighted in his work but also recognises the importance of a shared understanding of the ideas that underpin the education system concerned. Many initiatives fail because of a disconnect between the theoretical ideas that underpin policy and practice; making explicit and surfacing different perspectives on those ideas in all levels of the system and defining ‘collective action’ for different professional groups is a crucial part of implementing educational change.

Teachers do not work in isolation. They are part of a cultural system, seeking to improve the lives of the population through a commitment to quality education. How the people working in the different levels of the system interact with each other will ultimately determine whether these changes are sustainable, and whether the TPD can be implemented equitably at scale. Our analysis and experience suggest that more needs to be done at the school and community level to create conditions in which teachers are trusted, and learning about teaching becomes a shared endeavour between professionals at different levels of the system, rather than the handing down of perceived wisdom from ‘experts’ to those on the ground.

Acknowledgements:

This work was funded by the Scottish Government. It could not have been completed without the support of the Ministry of Education Officers in Zambia, or the expertise of World Vision Zambia — our implementing partner. We would like to thank Prof Freda Wolfenden and Dr Jennifer Agbaire for helpful feedback as the paper developed.Akyeampong, K., Lussier, K., Pryor, J., & Westbrooke, J. (2012). Improving teaching and learning of basic school mathematics and reading in Africa: Does teacher preparation count? International Journal of Education Learning and Development, 33(3), 272-282.

Baba, T., & Nakai, K. (2009). Teachers’ institution and participation in a Lesson Study project in Zambia: Implication and possibilities. The Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 12(1), 107-118.

Boateng, P., & Wolfenden, F. (2022). Moving towards successful teacher professional development in the Global South. Foundation for Information Technology Education and Development. https://tpdatscalecoalition.org/publication/successful-tpd-briefing-note/

Bold, T., Filmer, D., Martin, G., Molina, A., Rockmore, C., Stacy, B., Svensson, J., & Wane, W. (2017). What do teachers know and do? Does It matter? Evidence from primary schools in Africa (Policy Research Working Paper 7956). World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/882091485440895147/pdf/WPS7956.pdf

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513.

Dembele, M., & Miaro-II, B.-R. (2013). Pedagogical renewal and teacher development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and promising paths. In B. Moon (Ed.), Teacher education and the challenge of development: A global analysis (pp. 183-196).

Elmore, R.F. (1980). Backward mapping: Implementation research and policy decisions. Political Science Quarterly, 94(4), 601-616. https://doi.org/10.2307/2149628

FIT-ED. (2023). Empowering Teacher Initiative. Empowering Teachers Initiative - TPD@Scale Coalition (tpdatscalecoalition.org)

Fullan, M.G. (2007). The new meaning of educational change (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

Gaved, M., Hanson, R., & Stutchbury, K. (2020). Mobile offline networked learning for teacher Continuing Professional Development in Zambia. World Conference on Mobile, Blended and Seamless Learning. https://www.learntechlib.org/j/MLEARN/v/2020/n/1/

Higher Education Authority, & Management Development Division, Cabinet Office. (2022). Strategic Plan 2022-2026. Minsity of Education. https://hea.org.zm/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/HEA-STRATEGIC-PLAN-2022-2026-Final.pdf

Jung, H., Kwauk, C., Nuran, A., Perlman Robinson, J., Schouten, M., & Tanjeb, S. (2016). Lesson Study: Scaling up peer-to-peer learning for teachers in Zambia. The Brookings Institute. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3956230 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3956230

Kalaluka, K. (2024). A deep dive into the ZEST endline data (in preparation).

Kelly, P. (2006). What is teacher learning? A socio-cultural perspective. Oxford Review of Education, 32(4), 505-519.

Mabele, W., Likoko, S., & Onganyi, O. (2023). Future of teacher professional development in Kenya: Strategic leadership approach. European Journal of Education Studies, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v10i1.4658

May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, embedding and integrating practices: An outline of Normalisation Process Theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535-554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509103208

Murphy, P., & Wolfenden, F. (2013). Developing a pedagogy of mutuality in a capability approach: Teachers’ experiences of using the Open Educational Resources (OER) of the teacher education in Sub-Saharan Africa (TESSA) programme. International Journal of Educational Development, 33, 263-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.010

O’Sullivan, M. (2010). Educating the teacher educator—A Ugandan case study. International Journal of Educational Development, 30, 377-387.

Phiri, N. (2020). Exploring the effectiveness of continuing professional development (CPD) through lesson study for secondary school teachers of English in Lusaka, Zambia. Multidisciplinary Journal of Language and Social Sciences Education, 3(1), 68-97.

Pritchett, L. (2015). Creating education systems coherent for learning outcomes: Making the transition from schooling to learning. RISE. https://www.riseprogramme.org/sites/www.riseprogramme.org/files/inline-files/RISE_WP-005_Pritchett_1.pdf

Putnam, T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Education Researcher, 29(1), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029001004

Rogoff, B. (2008). Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In K. Hall, P. Murphy, & J. Soler (Eds.), Pedagogy and practice: Culture and identities. (pp. 58-74). Sage.

Schweisfurth, M. (2015). Learner-centred pedagogy: Towards a post 2015 agenda for teaching and learning. International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 259-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.10.011

Scott, D. (2010). Education, epistemology and critical realism. Routledge.

Seleznyov, S., Lin Goel, S., & Ehren, M. (2024). International policy borrowing and the case of Japanese Lesson Study: Culture and its impact on implementation and adaptation. Professional Development in Education, 50(1), 59-73.

Shulman, L.S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15, 4-14.

Soler, J., & Fletcher-Campbell, F. (2022). The evaluation of “equity” within TPD@Scale. [TPD@SCale Briefing Note]. Foundation for Information Technology Education and Development. https://tpdatscalecoalition.org/publication/equity-briefing-note/

Stutchbury, K. (2019). Teacher educators as agents of change? A critical realist study of a group of teacher educators in a Kenyan university [Doctorate in Education, The Open University]. http://oro.open.ac.uk/67021/

Stutchbury, K., & Biard, O. (2023). Practical theorising for the implementation of educational change: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Educational Development, 98, 102746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102746

Stutchbury, K., Gallastegi, L., & Woodward, C. (2019). Supporting open practices with teachers in Zambia. Journal of Learning for Development, 6(3), 208-227.

Stutchbury, K., Gallastegi, L., Woodward, C., & Phiri, J. (2023). Zambian Education School-based Training (ZEST): Endline Evaluation Report [Project report]. The Open University. https://oro.open.ac.uk/94372/1/ZEST%20Endline%20Report%20final_Nov_23.pdf

Stutchbury, K., Woodward, C., Phiri, J., Sampa, F., Biard, O., & Gallastegi, L. (2023). Instructional leadership—What it is and why it matters. UKFIET. https://www.ukfiet.org/2023/instructional-leadership-what-it-is-and-why-it-matters/

Tao, S. (2013). Why are teachers absent? Utilising the Capability Approach and Critical Realism to explain teacher performance in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 33, 2-14.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher pyschological processes. Harvard University Press.

Wedell, M. (2009). Planning for educational change: Putting people and their contexts first. Continuum.

Westbrook, J., Durrani, N., Brown, R., Orr, D., Pryor, J., Boddy, J., & Salvi, F. (2014). Pedagogy, curriculum, teaching practices and teacher education in developing countries. Department for International Development.

Wolfenden, F. (2022). TPD@Scale: Designing teacher professional development with ICTs to support system-wide improvement in teaching. TPD@Scale Coalition for the Global South. https://tpdatscalecoalition.org/publication/tpdatscale-working-paper/

Woodward, C., Stutchbury, K., Gaved, M., & Gallastegi, L. (2022). Internet not available! Using offline networked learning to enhance teachers’ school-based continuing professional development in Zambia. Pan Commonwealth Forum 10, Calgary, Canada. https://doi.org/10.56059/pcf10.608

Author Notes

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1915-5753

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4857-5797

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2046-5457

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9022-1824

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6480-6818

Dr Kris Stutchbury is a Senior Lecturer in Teacher Education at the Open University. She has 20 years of experience as a secondary school teacher. She led the Open University Initial Teacher Education programme and now teaches in the Applied Master’s in Education. Her research focuses on pedagogic change, teacher learning, teacher education and the issues surrounding implementation. She is the Academic Director of TESSA and co-led ZEST (Zambian Education School-based Training) — a seven-year programme of activity in Zambia designed to enhance the current system of school-based continuing professional development. Kris is PI for Achieving Quality, Equity, Efficiency and Sustainability in TPD@Scale in Zambia’ — a new research project that is part of the Empowering Teachers Initiative. Email: Kris.stutchbury@open.ac.uk

Dr Lore Gallastegi is a senior lecturer in Education at the Open University. She is a Staff Tutor based in Scotland with responsibility for associate lecturers in the Education Studies (Primary) degree. She represents the Open University in Education forums in Scotland and has been involved in the Scottish Government’s International Development programme for over 10 years. She worked on a research and development programme in Malawi, designed to encourage more girls into teaching and co-led ZEST. Email: lore.gallastegi@open.ac.uk

Clare Woodward is a retired lecturer in education. After a career in English language teaching, she joined the Open University to work on a multi-million pound development project in Bangladesh, designed to improve the quality of English Language teaching — English in Action. She specialises in using video to support teacher development and used this expertise to lead the development of video resources to support ZEST. She also worked on the Open University Education Studies (Primary) degree and PGCE programmes, developing video resources for students. Email: clare.woodward@open.ac.uk

Olivier Biard is a Programme Manager at the Open University. He brings over 20 years of experience in implementing development projects in Africa from the NGO sector. At the Open University he oversees research and development programmes, including TESSA, ZEST and OpenSTEM Africa — a programme bringing interactive digital resources that support practical science to secondary schools and universities in Ghana and Kenya. His research interest is in implementation and how it can be done effectively. Email: Olivier.Biard@open.ac.uk

John Phiri is a project co-ordinator at World Vision as part of the Education Programme Team. He has eight years of experience as a teacher, a school inservice co-ordinator and then a zonal inservice co-ordinator. He was a provincial education specialist for Teaching at the right level. At World Vision, John was project co-ordinator for ZEST, organising the Endline Evaluation. He is currently project manager for ‘Achieving Quality, Equity, Efficiency and Sustainability in TPD@Scale in Zambia’ — a new research project that is part of the Empowering Teachers Initiative. His research interests include TPD, educational technology, foundational learning and international development. Email: john_phiri@wvi.org

Cite as: Stutchbury, K., Gallastegi, L., Woodward, C., Biard, O., & Phiri, J. (2024). Teacher professional development @scale: Achieving quality and sustainability in Zambia. Journal of Learning for Development, 11(2), 237-252.