VOL. 3, No. 2

The Journal of Learning for Development (JL4D) was conceived in January 2013, in discussion with Professor Asha Kanwar and colleagues at the Commonwealth of Learning, Vancouver. Our aim was to create a new space in the journal field, dedicated to the intersection of learning for development, in other words how learning could support and bring about development. So this was not envisaged to be another journal of distance and online learning, although it aims to provide a focus for that field amongst others in terms of the educational dimension, but for all innovation in learning that had as an aim to contribute to social and economic development. As the website notes, ‘JL4D publishes research articles, book reviews and reports from the field from researchers, scholars and practitioners, and seeks to engage a broad audience across that spectrum. It aims to encourage contributors starting their careers, as well as to publish the work of established and senior scholars from the Commonwealth and beyond.’ I spent 2013 with Dr Mark Bullen, then Education Specialist for eLearning at COL, Patricia Schlicht, Programme Assistant at COL, and Dr Godson Gatsha, Education Specialist (Higher Education) at COL, designing and planning the journal, and we launched with a Call for Papers in the autumn of that year, with the first issue appearing early in 2014.

So now, three years later, as I step down from the position of founding Editor in Chief, I would like to review with readers the extent to which we have succeeded, and how the character of the Journal is developing. While we wanted to create this new space, we could not know in advance whether there would be contributors or readers. So how have we done?

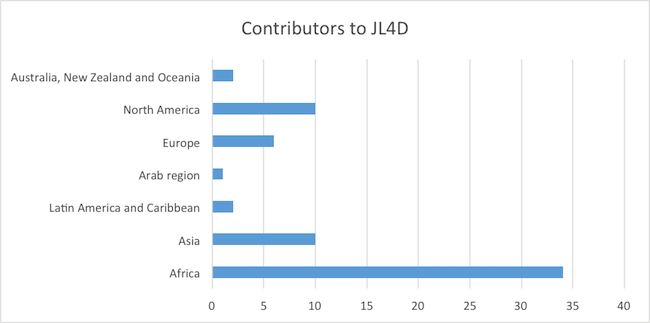

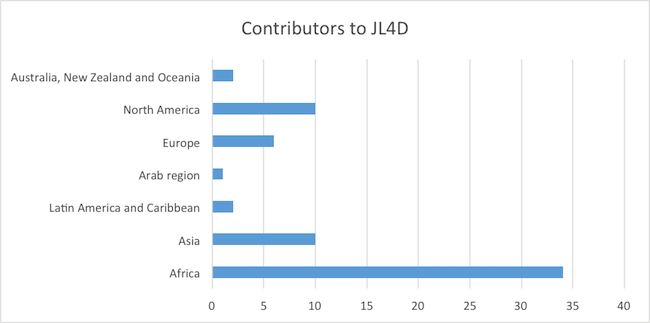

We have produced 6 issues in the years 2014-2015, and in total 20 research articles, including some invited articles from senior leaders in our field in the first issues; 10 case studies and reports from the field; 8 book reviews and 4 other items including commentaries, editorials, etc. We have published 42 items from 65 authors from major world regions (Fig. 1).

We can say at this stage that we have certainly elicited a response from countries in development, if we can distinguish in this way from those richer countries or from the ‘Global North’. It is gratifying to see such strong scholarly response from these regions and from Africa in particular, in the light of concerns about knowledge being produced and defined by the Global North for consumption in the South: this journal is contributing to the instruments that seek to reverse that imbalance.

Figure 1: JL4D papers from around the world

In terms of the major themes addressed in the Journal across all categories of writing, while it is difficult to classify, I can summarise in the following way.

The two largest areas of contribution have been:

While this is not differentiated from many journals engaged with innovation with technologies for education, the fields of application reveal thematic settings that are specific to countries in development, or the Global South. These include:

So it is clear that both the provenance and the thematic priorities that have emerged in the first two years of the Journal’s record of publishing speak to the developing world. I would hope, however, that the framing of innovation in learning for development would also be taken up by the richer countries, who are of course also themselves in development, that is to say, are equally concerned with social and economic interventions to improve the lives of their citizens, albeit from a different base than the rest of the world. It remains true that over and above the universality of relevance for development thinking, there are severe and increasing inequalities in the richer countries, with the re-emergence of social marginalisation at levels that have not been seen for 30 years in many developed parts of the world. The aspiration therefore is not only that the JL4D continues to provide a platform for knowledge to be produced in the Global South, but also that colleagues in the North accept the invitation to frame and analyse their educational innovation for development purposes also.

We should review, finally, the extent to which the articles published have helped the field understand more deeply how education can contribute to development. I set out in my first editorial in early 2014 how policy makers have for the most part moved beyond believing that education is solely to be understood as human capital development for economic growth, accepting that it is one of the most important elements for providing the context in which individual, families and communities can be better equipped, following Sen (2001), to make choices about their lives. This thinking underlay the UN Decade of Education for Sustainability 2005-2014, where a set of tasks was allocated to UNESCO in support of this broad goal, to (UNESCO, 2012, p. 11):

The UNESCO review of the decade in 2012 makes clear that in addition to curriculum focus or refocus on issues of sustainability, climate change, environmental protection etc., there is awareness of a need to focus on pedagogic innovation. Learners skilled and knowledgeable about sustainability need learning competencies that have been realised in pedagogic innovation in methods such as discovery learning, critical thinking, interdisciplinary learning, systems approaches and so on, as well as a range of progressive education practices that support student-centred flexibility (Tait, 2016). This journal’s focus has been envisaged as lying exactly at that convergence of innovation in learning for development purposes. The 2015 agreement on Sustainable Development Goals, with its commitment to Goal 4 for innovation at all levels including post-secondary and lifelong learning, makes this focus all the more central to the tasks of those concerned with education for development. We should, however, add that the traditions of distance learning, reconceived through the digital revolution as e-learning or online learning, now also add very powerful tools both to the potential of scale and pedagogy. There remains, however, a very considerable task ahead of all of us, to rethink how education for sustainable development demands change across all subject areas, building and exploiting digital capabilities, and embedding skills and understanding that will equip our citizens and workforces to provide better lives for themselves now and for the future.

It is difficult for educators to immerse themselves in development thinking and recognise how education contributes as more than a ‘thing in itself’, but as one of an array of crucial streams of activity for human and social development. We have been able to publish articles addressing major focus areas for development, e.g., health, schooling, teacher development, agriculture, and community development that are purposefully constructed with such explicit goals. Taking that dimension of analysis into all programme areas, in partnership with the new thinking needed about sustainability, represents an agenda as ambitious as it is essential. This journal represents one important space where this work can focus.

So, in conclusion, I wish the new Chief Editor Anne Gaskell all strength and success in taking the Journal forward, in partnership with Dr Sanjaya Mishra at COL. I continue in the role of Emeritus Editor and will take a close interest in the field as a whole as well as offer support to the Journal.

References