2024 VOL. 11, No. 2

Abstract: Development for empowerment focuses on leveraging education via digital technologies and micro-credentials for training and education as part of the integration, social inclusion and capacity building for displaced persons. Development for empowerment builds upon the previous concepts of development including Amartya Sen’s ‘development as freedom,’ the core concept of education and learning as development, and the use of digital technologies for building human capacity so people can make their own choices and pursue the lives they wish to lead. Development for empowerment for refugees broadens the construct of development and is integral to promoting and nurturing ‘equity, access and success’ amongst refugee populations. The authors highlight critical resources that support the basic tenets of human empowerment such as the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights, the UN’s Basic Needs Approach to Refugees, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, and the key strategies of online delivery and micro-credentials development. Moreover, the authors emphasise that the integration, social inclusion and integration of refugees is a highly complex construct to implement and sustain, thus reflecting the constant tension of refugees’ emotional desire to return home versus rebuilding a new life in a new country. In the final analysis, ‘development for empowerment’ + open and distance learning + digital micro-credentials create a powerful synergy for serving refugees and fulfilling the spirit of preserving human rights through education and the pursuit of one’s chosen life as a precious human ideal.

Keywords: refugees, integration, equity, access, inclusion, development, micro-credentials, online learning, human rights

We conclude that educating people is a vital component of development. It should not be seen primarily as the creation of human capital for the purpose of economic production, but as the nurturing of human capability that gives people the freedoms to lead worthwhile lives. This suggests that education for the 21st century should develop people’s capacity to become self-directed learners. (Daniel, 2014).

The concept of ‘learning for development’ has evolved and changed over the past twenty years (Daniel, 2014; Panda, 2023; Tait, 2014). Perhaps more importantly, development has matured to reflect more than simply economic expansion, personal gain or national GDP. It has inevitably expanded beyond geographic and economic boundaries. As Sir John Daniel (2014) so eloquently reminds us by drawing upon Amartya Sen’s (1999) concept of ‘development as freedom,’ development is pursuing one’s preferred life with freedom of choice to pursue and nurture one’s human capacities to the full extent for the individual, the community, society and the nation. Infused within this broader pursuit and conceptual framework of development, one can embrace Sen’s (1999) core ‘development as freedom’, where equity, equal opportunity, social justice and inclusion are core attributes of all aspects of development.

Inevitably, we return to a core concept of ‘development’ where education is a human right and learning is a core attribute of development. Lifelong learning and self-directed learning become development tools that contribute to identity, community, and skills development (Panda, 2023). Development embraces a bottom-up rather than top-down approach, combining a mix of capacity building and grass-roots technology applications (Daniel, 2014; Panda, 2023). The concept of ‘development for empowerment’ is a synthesis of human capacity building and modern digital technologies (online and micro-credentials) to empower displaced persons to leverage their futures through education and learning for promoting the use of open and distance learning (COL, 2024).

Development for empowerment for refugees broadens the construct of development and is integral to promoting and nurturing ‘equity, access and success’ amongst refugee populations. This paper builds upon the concept of development as a viable approach for conceptualising the role of education and open and distance learning for refugees and other persons displaced due to war, famine, natural disasters, dictatorships, and global shifts in environmental, and political and economic power. Development for empowerment leverages the capacity of refugees to maximise their individual capacity to meet challenges, define future goals, and, through various supports, rebuild their lives (Commonwealth of Learning, 2024). In essence, learning and development are interwoven into fostering human resilience and empowerment in order to return to the pursuit of one’s life.

Micro-credentials are not new to education. During the latter half of the 20th century universities, community colleges, and higher education institutions across the globe offered non-credit continuing education and short-term training for adults. The primary limitation of these offerings was weak evaluation and assessment. Most of these resulted in participants receiving certificates of attendance or participation, rather than formal validation and certification of specific skill domains (McGreal & Olcott, 2022).

The recent trend towards micro-credentials has been driven by greater demand for credentials that are pathways from school to work and are of shorter duration than traditional degrees and certificates. This does not diminish the value of degrees and certificates, however, the massive debt accumulated by students is also driving a push towards alternative digital credentials (International Council for Open and Distance Education [ICDE], 2019; COL, 2019; McGreal & Olcott, 2022). The differentiating factor of micro-credentials in 2024 is twofold. First, most, if not all, short-term micro-credentials will be storable and accessible digitally (ICDE, 2019). Second, and more importantly, rigid assessment processes to validate minimum levels of competency will be employed to certify different levels of skill proficiency (Credentials as You Go, 2024; McGreal & Olcott, 2022; Olcott, 2021).

For example, we could develop a micro-credential for learning to play the guitar at Level I, II, and III. Each level has progressively more difficult knowledge and performance requirements. Each level is only certifiable when the student completes each competency at a designated performance level.

Why do micro-credentials have the potential to be a viable delivery for serving the needs of refugees? First and foremost, unlike traditional training and educational programmes for adult learners, which are often advocated as ‘convenient’ for the returning adult student, there is no need to rush. Conversely, serving refugees is contingent upon provider capacity to mobilise efficiently because expediency and immediacy, not convenience, are the critical drivers towards equity, access, and success.

A highly integrated implementation strategy that brings together training, micro-skills, and digital tools to leverage equity, access, and success is needed. The natural connection to use micro-credentials for fast-track training for refugees using open and distance learning methodologies is a sound strategy and provides an immediate social and community means to begin the first phase for assimilation and integration.

The general global humanitarian crisis of refugees is complex. The United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) data reports that refugees comprise 1.6 million people annually and that the total number worldwide has seldom dropped under 10 million since 1982 (Concern Worldwide, 2024a). The total has accelerated recently due to the Gazan, Syrian, and Ukrainian conflicts.

The causes of the global humanitarian crisis of refugees are equally complex. Armed conflict is perhaps the most common cause known to the public with cases such as the recent Gazan, Syrian, and Ukrainian wars. And, whilst the core of conflict is based upon violence, the fact is not all violence is conflict, such as the attacks on the Rohingya people in Rakhine State where refugees are a result of massive violations of human rights. Additional factors contributing to this humanitarian crisis are climate change, migration, hunger and famine (Concern Worldwide, 2024; Olcott et al., 2023).

Indeed, the global humanitarian crises across the globe are disheartening and disconcerting for the human condition. We now have over 30 million refugees worldwide. The range of countries includes Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Ukraine (Concern Worldwide, 2024). And just when we thought it could not take a dramatic turn for the worse, the Gazan conflict between Israel and Palestine erupted in October 2023.

The UN Refugee Agency recently reported:

In the past decade, the global refugee crisis has more than doubled in scope. In 2022, the UNHCR announced that we had surpassed the 100 million mark for total displacement, meaning that over 1.2% of the global population have been forced to leave their homes. As of mid-2023, that also includes 30.51 million refugees. Over half of those refugees come from just three countries [Syria, Afghanistan, Ukraine]. These numbers are high — almost beyond comprehension — but each one represents a person who has been forced to leave everything behind due to circumstances beyond their control. (Concern Worldwide, 2024, p. 1)

The authors suggest, respectfully, that the reader may pause here and review the UN Declaration of Human Rights, published in 1948 by the UN (see reference list). This document is essentially the core foundation of all UN educational and humanitarian initiatives and, most importantly, its contents personify the very spirit of Sen’s ‘development as freedom’ and the rights of human beings to pursue the life they choose under the protections of life, liberty, property, and humane treatment reflective of the preservation of human respect, dignity, and integrity. If the reader remembers and learns only one concept from this paper, let it be the exponential value of the Declaration of Human Rights as the core foundations for the rights of all peoples.

The development of Education, Training and Employment opportunities offers a strong model for successful integration. The use of advanced ICT-supported learning in such environments offers new creative options for teaching and support (Brown, 2023; Brown, et al., 2023). Micro-credentials suggest expediency, which is often a critical factor for serving displaced persons effectively and efficiently (McGreal et al., 2022; McGreal & Olcott, 2022; Mays, 2022; Makoe & Olcott, 2021).

ICT-supported learning and digital resources can play an essential part in producing a resource of permanent value to educators dealing with migrant and refugee needs, enhancing self-sufficiency and autonomy, while, at the same time, delivering parallel training and upskilling methodology to provide permanent benefit to refugee participants. The secondary benefit is construction of a viable and transferable training system and content that enhances the career prospects and employability of trainee beneficiaries (Carretero et al., 2015).

Indeed, implementing refugee education, assimilation and integration into a new environment requires a broader ‘development for empowerment’ to empower both host communities, educators, and displaced refugees to collectively reframe development for creating alternative futures. Displaced persons and/or refugees are not just those existing outside their own nation; displacement can create refugee status for many within the borders of their home country as shown in Gaza, Sudan, Syria and Ukraine.

It would be naïve to ignore the immense impacts that refugees have on their host countries — even transition countries (Romania is a case in point). Moreover, the shifting political landscape is moving towards more populist governments, where minority and immigrant populations are often viewed negatively. Indeed, the citizens of host nations have concerns about national resources directed at refugee populations and the impact of integration at local levels.

This paper presents a case for combining open online education with digital micro-credentials as a tool to support and train refugees and to take them from a situation of basic social inclusion to one of social integration, where they gain, with improved independence, increased self-esteem, better employment, and well-deserved democratic rights. At the same time, leveraging micro-credentials for refugees is not an easy, silver-bullet strategy and the magnitude of social, cultural, economic, and educative issues this raises for host countries and educational providers is immense.

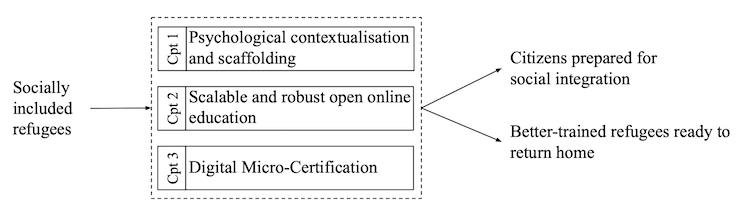

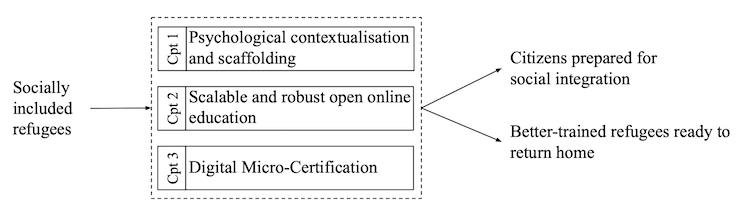

The robustness of this approach comes from the benefit of training for social integration, while, at the same time providing certificated learning outcomes, that can be used for future education and employment opportunities if refugees are able to return to their country. This paper presents a conceptual framework (development for empowerment) for identifying the causal elements necessary for the transition of socially included refugees to socially integrated citizens. This is followed by a detailed analysis of each of the three components that compose it:

As a descriptive study, this article draws upon theoretical constructs, previous literature, case studies, and practical experience of the authors in leadership, online learning, and the development and management of micro-credentials. The research questions for this paper were:

The first step for supporting refugees fleeing from extreme difficulties or conflict at home is obviously enabling them to enter a country and provide them with the basic support for survival, i.e., safety, accommodation, food, etc. This basic assistance is of great importance and can be seen as a fundamental part of what is termed ‘social inclusion.’ However, from the perspective of a country providing such support, this is a short-to-medium term process that is difficult to maintain over time if viewed in terms of the economic equation of what is provided against what is received.

Furthermore, any democratic system requires that a given population not only enjoys the benefits of living in such a country but also accepts the responsibilities of being a citizen there and actively takes part in supporting and maintaining its social cohesion and economic wellbeing. In the case of refugees, mere social inclusion is not enough; they need to be integrated into the economic reality of the country with training in the necessary skills and knowledge required to gain meaningful employment, pay taxes, and participate in the democratic process.

However, this transition from social inclusion to social integration is non-trivial, since there are problems both in getting the refugees to accept it, since they want to return home, and in finding educational institutions to provide the necessary training. The authors of this paper have conceptualised the psychological, pedagogical, and technological features required for an effective training and certification framework, which is presented in Figure 1 below.

Regardless of the strengths of each component in the framework, it will not work if the refugees in question are not prepared to participate. Hence, as can be seen in the figure, and will be further detailed in the following three sections, the results from training undertaken are people both well prepared for social integration, and also, if they desire, to return to their countries of origin with internationally recognised digital certificates that could help them advance professionally, once their countries recover from whatever difficulties had forced them to leave in the first place (Centre for Study of Democracy, 2022).

Despite the range of theoretical and practical frameworks that can be drawn upon to introduce the refugee context, perhaps the easiest to understand and has stood the test of time, is Maslow’s (1954) hierarchy of the basic needs of most human beings. As can be seen in Figure 2, physiological and safety needs are a high priority for all of us and yet for a refugee fleeing harm’s way in a war zone or a natural disaster, these needs are, in fact, a matter of life and death.

Figure 2 accentuates that the priority and largest needs for refugees are physiological and safety needs. This graphic also highlights that despite our typical view of these being sequential they are often thrown into disarray for refugees. At the same time, it is equally important to recognise that self-esteem and acceptance are powerful factors for social assimilation and integration by the host group. In essence, the first four levels are interconnected and reinforce refugee resilience that collectively empowers individual capacity and the potential of digital technologies to support refugees.

Interestingly, economic welfare or employment needs cut across both safety and self-esteem and refugees often emerge from their homeland devasted emotionally and psychologically. Maslow’s needs may have been conceptualised as sequential but life often does not cooperate, and simple and vulnerable human beings gravitate towards different levels of specific needs at any given time.

An observation related to the use of digital technologies in developing countries emerges by reverting to a well-known framework — Maslow’s Hierarchy. Human needs must be met first before people, in this case students, will gravitate towards technology and education. Technology, in and of itself, is not a panacea for resolving educational needs in the developing context. Without addressing poverty and limited economic viability, it is next to impossible for advocates for digital solutions to make their case, particularly to the rural populations that make-up the majority of the developing world. The reality is Maslow is not a simple framework for its readers. In fact, it reflects the cold hard truth that the power of education in the face of displacement, poverty, and lack of basic human needs is only too real.

Most refugees have had their self-esteem depleted, their confidence severely wounded, and their hope depleted by the stress of uncertainty. Love and belonging — feeling welcome and wanted — carry disproportional weight for most refugees as they adapt to many changes. The critical point here is that educators must recognise that for these refugees, crossing borders, settling into new shelter, and heading off to school is not that simple. Both children and adults alternate amongst these needs in Maslow’s hierarchy. All are vulnerable. As educators, we see digital technologies will not in and of themselves resolve these dilemmas for the refugee child or mother. The fusion of human and technology could not be more important than in the space of serving and supporting refugee populations.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UN Refugee Agency) has developed a Basic Needs Approach in the Refugee Response (UNHCR, 2022). Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to conduct a detailed analysis and assessment of the synergies between Maslow’s Hierarchy and the UNHCR resource, suffice it to accentuate that these align closely with serving the basic needs and skills of refugee populations. Taken together they provide a basic and easy conceptual approach for university staff to view the challenges and opportunities that can be brought to those in need.

Finally, implicit in the identified problems hindering the participation of refugees in education programmes in a host country is the underlying desire to return home. The temptation on their part is, therefore, just to wait, thinking that sooner or later they will be able to do this. However, studies show (Crea & Sparnon, 2017) that such people can hang on in a state of psychological hiatus sometimes for more than a decade without being able to go home, or without being better integrated into where they are. The presence of this component in the framework is necessary so that the relevant support can be provided to engage with refugees so they see the value of participating in training programmes, as can scaffolding the educational process once they have started.

It is not the best of times for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), with rising costs and increasing institutional debt. For example, forecasts have been made predicting the closure of up to 50% of American colleges in the next decade (Hess, 2018). Hence, any desire for them to accept the responsibility of training, essentially, non-fee-paying refugees to meet the employment needs of a given country by part of the government there is very optimistic! The sheer numbers alone make face-to-face (F2F) teaching impossible, given the number of places available at these HEIs. Open education has been long been proposed as a solution for a wide range of student needs over the years (Butcher et al., 2011; UNESCO, 2019) and once again here, in this context, could offer a way for refugees to reach higher levels of training, something that is key for social integration.

In its favour, there is the basic requirement for students to have online access, something possible from cheaply available computers or devices such as tablets or mobile phones. Even if they do not have their own broadband or network contract, such access is easily available in many public buildings such as libraries. Many HEIs offer such courses in concert with other quasi-private entities such as Coursera, edX, UC-Irvine, European MOOC Consortium, Western Governors’ University (WGU), FutureLearn, and many others (McGreal & Olcott, 2022).

The critical need for engagement and learning needs to be emphasised (Global Business Coalition for Education, 2016). Rights and inclusion are international issues — a fact not as widely represented in professional teaching formation as it should be. The removal of barriers to participation will be about asserting the primacy of a global vision that challenges traditional complacencies and inherited structures. This also emphasises the role ICT can play in achieving best practice and innovative quality. Barriers to equality stem from prejudice and ignorance. The removal of barriers can be addressed by legislation and monitoring practice. Deeper transformation can be achieved rapidly by educators seizing the opportunities offered by social difference and incorporating them in innovative learning paradigms.

The changes produced in both the human and technological aspects of the globalisation process shape how global education may now include various learning communities previously excluded by reasons of prejudice, discrimination or remoteness. We need to support learners across the globe to transcend barriers and address conflict and persistent discrimination by means of skilful application of potent technological tools in the metamorphosis of traditional educational systems to meet unprecedented levels of socio-economic transformation (OECD, 2015). Because migration and greater numbers of crisis-driven refugees are intimately linked to processes of globalisation and inequality, we can see the importance of linked-up thinking to develop adequate policy and educational responses (Bruce et al., 2018).

Before any type of online refugee engagement with training at HEIs can be considered, via scalable open courses, the underlying language skills and knowledge required have to be established (Read & Sedano, 2024). Following the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2022) basic social integration, including initial steps into the labour market, albeit in menial and far from ideal conditions, is arguably possible with an A2 level. However, for social integration, working in the knowledge economy or learning at HEIs, a high B1 to B2 level is required, which requires significantly more effort, resources, and training. Hence, while any field of knowledge could be considered here to exemplify the second component in the framework, a vitally important one, common to all refugees, would be how to learn the language of the host country.

The complexities of language acquisition in the context of emotionally and physically impacted refugees are significant and significant research has been published previously (Read & Sedano, 2021). Conversely, it is important to recognise that the entry way in a new environment where one’s native language may not be commonly spoken will elevate language training as a crucial priority for many refugees. The authors of this paper, although not as refugees, have experienced the process of immigrating to countries where their native language was spoken only in certain circles — business, education, government. The point is that learning a local language facilitates one’s immersion in meeting Maslow’s needs, particularly physiological ones and safety, and, over time, language opens doors of confidence and self-esteem, the far-reaching potential of love and belonging that allows us to thrive, not just survive, in our new setting. Language is our bridge to Maslow’s needs and that leads to the next bridge — education and training.

Language assimilation is critical for both growth in Maslow’s needs and for educational purposes. Moreover, using distance learning for the delivery of training to non-native language speakers of the delivery language has clearly shown this can be difficult for the learner. And it is not simply linguistic issues. Rather, it also begins to highlight the critical role of context, culture, and informal communications that, in the aggregate, affect refugee assimilation, growth in Maslow’s hierarchy, and the ability to learn effectively, whether in a F2F classroom, in front of a computer, or in hybrid scenario.

The reader may be asking, Does the language issue need to be addressed first (along with basic needs) before educational endeavours can be introduced? The obvious answer is to make language training part of the holistic assimilation and integration process. Research has been undertaken by the authors on the topic of language learning by refugees and migrants. An example can be seen in the ERASMUS + MOONLITE project and the recommendations made about how such language learning can be structured (The Moonlight Project, 2022). However, independence, which comes from consolidation in the labour market, or entering a higher education institution (HEI), requires a high B1 or, better still, a B2. Achieving these subsequent levels goes beyond what is typically available from free introductory language courses offered by charities or non-governmental organisations.

As argued by Read and Sedano (2021), the most effective way to address targeting language learning for refugees and migrants would be via a TLMI (Target Language as Medium of Instruction) MOOC. The course should be enhanced with the provision of subsequent F2F training of the concepts and skills studied online. In both the MOOC and the training, the pedagogic mechanisms needed to enhance interaction and language productivity skills would be based around three elements. Firstly, passive and active scaffolding with reinforced forum support. Secondly, identification of e-leading (pro-active, highly motivated) students and educational proxies (tutors or facilitators from the student community), before and during the training, to support others. Thirdly, and finally, attention to the activity of the participants, building on the concepts of investment, integration and performance, according to which the students become aware of their desire to learn, so they integrate into the learning group/community, and become more engaged in language learning and showing a high level of performance.

While training and learning are important, what is essential both to motivate the students and move them forward with their social integration, is that their studies are certified, providing evidence of prior learning. In the next section this topic is considered.

Micro-credentials are beginning to appear as an institutionally independent format for learning accreditation. They have been defined by the European Commission (2020) as a proof of learning acquired by students that are assessed against transparent standards. The proof is documented in terms of the learner’s details, achieved learning outcomes, how assessment was undertaken, the awarding body, any qualification framework level (if appropriate), and the credits obtained. While such credentials can be used to address the problems of verification and stackability outlined in the previous paragraph, they do not, in and of themselves, solve the economic problems that refugees and migrants face (McGreal & Olcott, 2022; McGreal et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2023; Makoe & Olcott, 2021).

However, as will be explored in the next section, if education is taken to be a basic right for the full development of the human personality, human rights, and fundamental freedoms, as per Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, then the certification costs could be absorbed by governments or directly by the European Commission. Additionally, the European MOOC Consortium has moved the micro-credential landscape forward with its Common Micro-Credential Framework (EMC, 2020), which is aligned with the credit standards of the EHEA.

We have accentuated that as a descriptive analysis this paper aligns more as a field study and/or case study, and less as a formal empirical research article. The two research questions addressed were: 1) the alignment of development for empowerment as a core framework to employ ODL and micro-credentials to serve refugee population assimilation and integration needs; and 2) the viability of micro-credentials as a strategy for addressing the expediency of serving the training, assimilation, and integration needs of refugee populations. It is possible to examine these separately.

The potential of micro-credentials is based upon expediency — the capacity to respond quickly to empower the development of a population (refugees) that is facing dire personal and emotional transitions. Empowerment and empathy are concepts that speak directly to the urgency faced by refugees and the role that providers and host countries can offer to displaced persons. Empowerment is not some play on semantics applied to the concept of development. As previously discussed, the concept of development has been, and will continue to be, a progressive term that is malleable and adaptive to the changing and complex Zeitgeists (norms and climate of a particular era) of the future. Micro-credentials are fast-tracking pathways to stability and survival and they are viable for meeting the urgency of refugees. In sum, there is ample support for the hypothesis that ‘development for empowerment’ is a viable framework to apply to refugees and using ODL micro-credentials. It is also a construct that will likely only grow in the future given the challenges faced by planet Earth.

The hypothesis for the second research question is that the analyses suggest digital micro-credentials — and perhaps non-digital offerings — are a potentially and viably sound approach to the urgency of serving the assimilation and integration training needs of refugees. This does not suggest there are no significant transition issues, resistance from the host-country population and oversight agencies, or economic and social considerations inside the country. However, that is not the purpose of this paper. This paper asks whether development for empowerment and the use of ODL micro-credentials are viable approaches for serving refugee populations. The authors have demonstrated that the answer to both hypotheses is yes.

Consistent with the focus of this paper, institutions considering the use of short-term micro-credentials may position their delivery focus on language training, basic skills and cultural assimilation education, depending on the particular digital skills assessment available to the refugee population. Many institutions are unsure where to make a start in refugee education. The most important advice is to be proactive, not reactive. There is always an initial desire to do something immediately, which is a natural human response. We suggest the following key questions:

A final word on assessment and competencies. The current trend towards micro-credentials places a high premium on quality and setting competency levels to be demonstrated by the learner at a minimum level that collectively results in performance validation and certification (McGreal & Olcott, 2022). The practical context of refugee education is that many refugees lack the time and resources to engage in high-level assessment certification processes. We need to help people with basic assimilation and functioning skills in an often entirely new and alien environment. We can wear our educator and our human being hats at the same time. In sum, much of what we do for refugees will be similar to giving badges out for participation in specific training activities and education. At the same time, part of the response of educational agencies to refugee education will be to build progressively higher levels of training, validation, and certification.

It is not clear to what extent refugees and migrants are able to move up Maslow’s hierarchy and go beyond basic social inclusion, in the sense of having somewhere to stay, belonging to a local community, and working in a menial fashion. What is clear, is that for them to progress in a similar way to other more fortunate people, education is of fundamental importance and, initially, language learning and, subsequently, skill-based knowledge related to their field of expertise are needed (inHERE, 2022; UNHCR, 2022; Sirius, 2022).

Apart from the economic questions relating to the costs of such study, which refugees may or may not be able to afford, there is also the question of the availability of relevant courses. As the number of people wishing to enrol in professional training and HEI study programmes increase, then it is not clear that the demand can be met by the available offerings. This situation supports the need to unbundle HEI study programmes into small learning scenarios that can be followed online. While such means of study are often not popular with refugees and migrants, due to their need for social contact and the value they ascribe to F2F activities, once some experience of such courses is obtained, initial resistance can be overcome. Blended approaches may be highly desired, particularly for language training, basic computer skills, and perhaps even some basic skills knowledge training (Altbach, 2002).

In order for online learning to complement, and in some cases, replace its F2F equivalent, students must have the relevant digital competences and digital literacy skills. It is often easy to assume that most ‘young people’ are ‘digital natives’, and, as such, are more than able to undertake their studies online. As has been noted in the literature (Prensky, 2009), this overly simplistic view of such capabilities does not in fact reflect the true situation. However, this drawback of online studies is not necessarily an unsurmountable obstacle, since most online platforms include some transverse introductory modules helping students to learn the meta-skills they need to study when using them.

As we reflect upon what has been highlighted in the literature (McGreal & Olcott, 2022), small online learning scenarios, that encompass specific skills or areas of knowledge, can provide vulnerable groups, or even mainstream students, who are not able to enter regular HEIs for whatever reason, with the opportunity to continue with their training needs as part of a life-long learning experience. As was noted in the previous section, the problem with such courses is that of certification, and also that of costs or portability of any certificates gained (Brown et al., 2020; Olcott, 2021; Makoe & Olcott, 2021).

When micro-credentials were highlighted by the European Commission as a key part of the second iteration of Europass (EU, 2024), the EDCI (Europass Digital Credentials Infrastructure) was proposed, and is being implemented as a framework that institutions could use to issue credentials. Implicit in this process is the understanding that the process is cost free, so there is no reason, a priori, that HEIs would need to charge to certify their courses. However, such charges are usually justified in terms of a business model based on the economic feasibility of producing and running such courses. This is normal, understandable, and acceptable, since there is no such thing as free! Someone, somewhere, is paying the associated costs (Olcott, 2021).

Therefore, if there is genuine political and social interest in moving from basic social inclusion to social integration, assimilating refugees and migrants into society, and moving the process from mere rhetoric to reality, then society itself must cover the costs. The financial underpinning of this educational process can be situated at the national level, covered by a part of the taxes paid there (and contributed to by the refugees themselves once they are integrated and in full employment), or at a higher level, as something undertaken by the European Commission (Miller et al., 2008).

This paper introduced the concept of ‘development for empowerment’ and the concept of employing ODL micro-credentials to meet the urgent needs of refugees in transition. Moreover, it has argued that empowering refugees, integrating ODL technologies, and enhancing gender equity, access and success are clearly important goals. The majority of refugees are women and children, which, in turn, suggests that ODL + micro-credentials will be essential for training mothers. The authors have addressed two basic research questions and demonstrated that: 1) ‘development for empowerment’ is a viable framework for addressing refugee populations, and 2) micro-credentials, vis-à-vis ODL digital technologies, are a potential and viable means to serve the training needs of refugees.

The plight of the refugee is a metaphor for mobile poverty. And yet, it is worse because they may have left behind brothers, sisters, fathers, friends and they do not know if or when they will ever return or if they will see those people again. Digital technology is no panacea for poverty, which is the real enemy of education and the human condition. At the same time, digital tools are one avenue for opening new doors and opportunities for displaced populations.

We have accentuated that most institutions will need to plan and reposition their arsenal of services and offerings in new ways — some online, some F2F and, certainly, many will be blended — since refugees need social interactions as much as they need food, shelter, and health care. At the very least they must feel they are not alone, that others care for them and are there to help them (Díaz Andrade & Doolen, 2016).

There is no unified definition of inclusive education. There are various determinations of the concept that depend on perspective and teaching context. The common factor to all definitions of inclusion is that they stem from the principle of human rights and are, therefore, defined more broadly because they relate to overall social inclusion and do not merely include the educational dimension of inclusion.

The surrounding environment should not be reduced to some abstract conceptualisation, divorced from everything except theoretical construction. Environment is not simply the physical space around people. Neither is it a reified space, removed from all consideration of control and domination in concrete social contexts. Environment is about other people, and about the relationships between people and the social structures that other people construct in terms of interaction, power-relationships, and hierarchy. Environment is the system (educational, economic, political, social) under which conditions of innovation and creativity, and meaningful learning are forged, tolerated, accepted, rejected or enhanced. Mass migration and increased numbers of refugees shape this environment profoundly and are now part of a permanent reality (English & Mayo, 2019).

Finally, issues and elements around design, inclusion and access connect to concepts of social justice in education. This is critical for strategic planning for future education systems and learning methodologies. This conceptualisation enables us to understand that engaging with and planning for refugee education and integration, like any measure concerning equity and enhanced inclusion, cannot be divorced from wider prevailing issues around power hierarchy and access to resources. Proactive learning strategies responsive to refugee needs are one tool among many intended to remove barriers to participation. The comprehensive nature of its vision means that it challenges the structures themselves.

At the apex of these strategies is a conceptual framework for the transition of social inclusion to social integration, which has been presented above. It can structure, scaffold, and certify learning in such a way as to motivate refugees and migrants to participate. The authors argue that its effectiveness comes from the way the training results enable people both to become better socially integrated into their new country, or, if so desired, to return to their countries of origin with internationally recognised digital certificates that can help them advance professionally once their countries recover from the difficulties and challenges that forced them to leave in the first place.

In conclusion, ‘development for empowerment’ + open and distance learning + digital micro-credentials create a powerful synergy for serving refugees and fulfilling the spirit of preserving human rights through education and the pursuit of one’s chosen life as a precious human ideal.

Altbach, P.G. (2002). Perspectives on internationalizing higher education. International Higher Education, (27). https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/ihe/article/view/6975

Brown, M. (2023). Leading in changing times: Building a transformative culture. In O. Zawacki-Richter & I. Jung (Eds.), Handbook of open, distance and digital education (pp. 509-525). Springer Singapore. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2080-6_28

Brown, M., McGreal, R., & Peters, M. (2023). A strategic institutional response to micro credentials: Key questions for educational leaders. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1-17. DOI: https://doi. org/10.5334/jime.801 https://storage.googleapis.com/jnl-up-j-jime files/journals/1/articles/801/646dff50356e4.pdf

Bruce, A., Graham, I., & Guardiola, M. (2018). Supporting learning in traumatic conflicts: Innovative responses to education in refugee camp environments, Exploring the micro, meso and macro. Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network 2018 Annual Conference. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325876603_Supporting_Learning_in_Traumatic_Conflicts_Innovative_Responses_to_Education_in_Refugee_Camp_Environments

Butcher, N., Kanwar, A. & Uvali-Trumbic, S. (2011). A basic guide to open educational resources (OER). Commonwealth of Learning/UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000215804

Carretero, S., C. Centeno, F. Lupiañez, C. Codagnone, & R. Dalet. (2015). ICT for the employability and integration of immigrants in the European Union: Results from a survey in three member states. JRC-IPTS Technical Report. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280659766_ICT_for_the_employability_and_integration_of_immigrants_in_the_European_Union_A_Qualitative_Analysis_of_a_Survey_in_Bulgaria_the_Netherlands_and_Spain

Centre for Study of Democracy. (2012). Integrating refugee and asylum-seeking children in the educational systems of EU member states: Evaluation and promotion of current best practices. https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/integrating-refugee-and-asylum-seeking-children-educational-systems-eu-member-0_en

Commonwealth of Learning (COL). (2019). Designing and implementing micro-credentials: A guide for practitioners. http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3279

Commonwealth of Learning (COL). (2024). What we do. https://www.col.org/what-we-do/

Concern Worldwide. (2023). The 10 largest refugee crises to know in 2024. https://www.concern.net/news/largest-refugee-crises

Concern Worldwide. (2024). The refugee crisis explained. https://www.concern.net/news/global-refugee-crisis-explained

Council of Europe. (2022). The common European framework of reference for languages. https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-

Crea, T.M., & Sparnon, N. (2017). Democratising education at the margins: Faculty and practitioner perspectives on delivering online tertiary education for refugees. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14-43. DOI: 10.1186/s412239-017-0081-y https://educationaltechnologyjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s41239-017-0081-y

Credentials as You Go. (2024). www.credentialasyougo.org

Daniel, J. (2014). What learning for what development? Journal of Learning for Development, 1(1). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1106076.pdf

Díaz Andrade, A., & Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quarterly, 40(2), 405-416. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26628912

English, L., & Mayo, P. (2019). Lifelong learning challenges: Responding to migration and the sustainable development goals. International Review of Education, 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45201174

European Commission. (2020). A European approach to micro-credentials. https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/micro-credentials

European MOOC Consortium. (EMC). (2020). EMC common microcredential framework. European MOOC Consortium, 1-13. https://emc.eadtu.eu/images/EMC_Common_Microcredential_Framework_.pdf

Europass. (2024). https://europa.eu/europass/en

Global Business Coalition for Education. (2016). Exploring the potential of technology to deliver education & skills to Syrian refugee youth. https://gbc-education.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/03/Tech_Report_ONLINE.pdf

Hess, A.J. (2018). Harvard business school professor: Half of American colleges will be bankrupt in 10 to 15 years. CNBC Make it. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/08/30/hbs-prof-says-half-of-us-colleges-will-be-bankrupt-in-10-to-15-years.html

International Council for Open and Distance Education. (ICDE). (2019). Report of the ICDE working group on The Present and Future of Alternative Digital Credentials (ADCS), 1-54. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b99664675f9eea7a3ecee82/t/5cc69fb771c10b798657bf2f/1556520905468/ICDE-ADC+report-January+2019+%28002%29.pdf

inHERE. (2022). Recommendations from the project: Enhancing the access of refugees to higher education in Europe and their integration. www.inHEREproject.edu

Maslow, A.H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Makoe, M., & Olcott, D.J. (2021). Leadership for development: Re-shaping higher education futures and sustainability in Africa. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(3), 487-500. https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/issue/view/25

Mays, T. (2022). Challenges and opportunities for open, distance and digital education in the Global South. In O. Zawacki-Richter & I. Jung (Eds.), Handbook of open, distance and digital education (pp. 321-336). Springer Singapore. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-981-19-2080-6_20

McGreal, R., & Olcott, D.J. (2022). A strategic reset: Micro-credentials for higher education leaders. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1). https://slejournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40561-022-00190-1

McGreal, R., Mackintosh, W., Cox, G., & Olcott, D.J. (2022). Bridging the gap: Micro credentials for development: UNESCO Chairs Policy Brief Form — Under the III World Higher Education Conference (WHEC 2021) Type: Collective X. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 23(3), 288-302. https://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/6696

Miller, R. Shapiro, H., & Hilding-Haman, K. (2008). School´s over: Learning spaces in Europe in 2020: An imagining exercise on the future of learning. Joint Research Centre, Scientific and Technical Report. European Commission, Brussels. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266160561_School's_Over_Learning_Spaces_in_Europe_in_2020_An_Imagining_Exercise_on_the_Future_of_Learning

The Moonlight Project. (2024). https://moonliteproject.eu/

OECD. (2015). Immigrant students at school — Easing the journey towards Integration. OECD Reviews of Migrant Children. https://read.oecd.org/10.1787/9789264249509-en?format=pdf

Olcott, D.J. (2021). Micro-credentials: A catalyst for strategic reset and change in U.S. higher education. The American Journal of Distance Education. DOI: 10.1080/08923647.2021.1997537

Olcott, D.J., Arnold D.J., & Blaschke, L.M. (2023). Leadership 2030: Renewed visions and empowered choices for European universities. European Journal of Open and Distance Learning (EURODL), 25(1), 74-92. https://sciendo.com/article/10.2478/eurodl-2023-0006?tab=article

Panda, S. (2023). Editorial — Changing perceptions of ‘learning for development’ in the new normal. Journal of Learning for Development, 10(2), i-vii. https://oasis.col.org/items/86bf3dd4-9c04-45fb-b34c-cacb349da8f0

Prensky, M. (2009). H. sapiens digital: From digital immigrants and digital natives to digital wisdom. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 5(3). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/104264/

Read, T., & Sedano, B. ( 2024) (in press). Consolidating language skills in a F2F training enhanced TLMI MOOC. In Innovations in learning technologies for autonomous language learning. Peter Lang.

Read, T., & Sedano, B. (2021). The role of scaffolding in LMOOCs for displaced people. Language and Migration, 13(2), 115-133. https://ebuah.uah.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10017/50621/role_read_L%26M%2013_2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/development-as-freedom-9780198297581?lang=en&cc=no

Sirius. (2022). Ukraine: Statement of support and access to inclusive education for all refugees. https://www.sirius-migrationeducation.org/statement-ukraine/

Tait, A. (2014). Learning for development: An introduction. Journal of Learning for Development, 1(1). https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/39/20

United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). (2022). Basic needs approach in the refugee response. https://www.unhcr.org/media/basic-needs-approach-refugee-response

UNESCO. (2019). Recommendation on Open Educational Resources (OER). https://en.unesco.org/about-us/legal-affairs/recommendation-open-educational-resources-oer

Author Notes

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8966-9680

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3051-1528

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4542-9305

Dr Timothy Read is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Computer Languages and Systems at UNED, Spain. He completed his first degree in Real Time Computer Science at the University of The West of England and his Doctorate in Cognitive Science at the University of Birmingham (United Kingdom). He worked at the University of Granada before moving to UNED in Madrid. He is the co-founder of the ATLAS research group and has directed several national and international projects on applying Information and Communication Technologies to Languages for Specific Purposes. He currently works in the areas of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning and Language Massive Open Online Courses, and their applications for social inclusion and employability, and the role of analytics in these areas. As well as his academic career, he worked in different international companies, including Rolls Royce, Hewlett Packard, and the telecommunications company ITT. He has been awarded the titles of EDEN Fellow and EDEN Senior Fellow and was President of EDEN UK. Email: tread@lsi.uned.es

Dr Alan Bruce is CEO and Director of Universal Learning Systems — an international consultancy firm specialising in research, learning innovation and project management for the educational, development and management sectors. He lectures for the National University of Ireland Galway in equality, diversity and systematic training. An international academic adviser for the University of Memphis, he was appointed to its Graduate Faculty in the Department of Psychology and Counselling in 2014. In 2014, Dr. Bruce was appointed to the Board of NCRE (National Council on Rehabilitation Education) in Washington, DC. In 2018 he was appointed to the Board of CORA (Council on Rehabilitation Accreditation) in Memphis, Tennessee. Senior Research Fellow in Education with the University of Edinburgh (2009-2014), he also lectures in the Master’s in European Project Management in Florence, Italy. In 2015 he was elected as Senior Fellow of EDEN (European Distance and E-Learning Network). In 2010 he became Vice-President of EDEN. In 2014 he was appointed Associate Professor with UOC (Open University of Catalonia) in Barcelona on conflict resolution and innovative learning. In 2016 he was International Expert for Innovative Learning with the Open University of Hong Kong and the launch of the Institute for Research in Open and Innovative Education (IROPINE). In 2016 he was appointed as Visiting Professor for Global Learning in the Changhua University of Education in Taiwan. In 2016 he developed the Master’s in Online, Open and Distance Learning for Charles Sturt University, Australia. He was also appointed as Learning Design Expert with Universidad Nacional de Educación (UNAE) in Ecuador. Email: abruce@ulsystems.com

Dr. Don Olcott, Jr, FRSA is a Consultant Associate with Universal Learning Systems, specialising in global open and distance learning; and Professor Extraordinarius of Leadership and ODL at the University of South Africa. Don was the 2024 recipient of the United States Distance Learning Assocation (USDLA) Leadership Award for outstanding contributions to open, distance and online learning. He was the 2023 recipient of the ICDE Prize of Excellence for Lifelong Contributions to open, flexible, distance and online learning. Don is a Senior Fellow of EDEN Digital Learning Europe and was Chair of the EDEN Council of Fellows for 2021-2022. He was adjunct Professor of Leadership and ODL at the University of Maryland Global Campus from 2011-2021. Dr. Olcott is former Chief Executive of The Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) in the UK (2007-2011) and former Chairman of the Board of Directors and President of the United States Distance Learning Association (USDLA). Dr. Olcott was the 2013 recipient of the International Council of Distance Education (ICDE) Individual Prize of Excellence for his leadership and contributions to global open and distance education. He was the 2016 Stanley Draczek Outstanding Teaching Award recipient from the University of Maryland Global Campus for excellence in online teaching and learning. Email: don.olcott@gmail.com

Cite as: Read, T., Bruce, A., & Olcott, D. (2024). Development for empowerment: Mobilising online and digital micro-credentials for refugees. Journal of Learning for Development, 11(2), 253-269.