VOL. 1, No. 2

Most countries have enshrined the right to education in their constitution but, in reality, to fulfil this commitment, countries do face a number of challenges. And this is true with the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, which unlike other countries has a long history of war, conflicts, insurgency and hence insecurity. Although there have been positive steps towards rehabilitation of the education system and signs of promise can be seen in its achievements, access to quality education remains inequitable, particularly across the provinces as a result of remoteness and geographical isolation, harsh climate, insecurity which impedes growth and sustainability of access points, high gender gap in all sectors of education, particularly from the lower secondary stage to the higher stages of education, poor infrastructure prevalent in most schools, untrained teachers and the low number of female teachers affecting participation, retention and continuity of studies.

This paper highlights the current school educational status in Afghanistan to reveal the daunting challenges still existing for the country to achieve its constitutional goals. It also points out how an Open schooling system can take charge of the challenges in Afghanistan to provide a channel of educational opportunities to those who cannot and do not go to school, particularly females.

Education is central to development. It is fundamental for the construction of democratic societies, being among the most powerful instruments known to reduce poverty and inequality. Therefore, governments around the world including Afghanistan, whose citizens have suffered too long and none more so than its children, place considerable emphasis on investments in education and, in particular, on the provision of schooling. Schooling has direct implications for individual outcomes, for national aggregate outcomes, and for the distribution of outcomes across society. In fact there is a direct economic relationship between government spending and the returns on investments in education.

Further, international committees established under human rights treaties have laid down the following five criteria with respect to the rights of children to education.

Education must be:

Most countries have enshrined this right to education in their constitution but in reality to fulfil this commitment countries do face a number of challenges. And this is true with the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Unlike other countries Afghanistan has a long history of war, conflicts, insurgency and hence insecurity. In spite of this there have been positive steps towards rehabilitation of the education system and achievements and signs of promise can be seen.

According to the National Educational Strategic Plan (NESP-II), since 2001 there has been a seven-fold increase in demand for education in Afghanistan, which has placed significant pressure on the existing system. The demand for education has continuously exceeded supply, leading to increased donor dependence. There are now nearly 7 million children enrolled in school, over 37 % of which are girls, compared to slightly more than 1 million enrolled just seven years ago. However, 42% of school age children, mostly girls, are out of school. By 2020, about 8.8 million children are likely to require access to primary education and even with drop outs the secondary attendance will also increase by 3 million.

However, many studies have revealed that daunting challenges still exist in Afghanistan for the country to face to achieve its constitutional goals, from which it is evident that the formal schooling system as a single delivery system will not be able to realize the cherished hopes and aspirations of Afghanistan to universalise school education. The country has no choice but to look for an alternative system that compliments / supplements the formal school system and, in this context, Open Schooling finds a relevant place.

Many countries around the world, initiated the Open and Distance Learning (ODL) system to augment opportunities for education, particularly as an instrument for democratising education and making it a lifelong process. Many have strategically placed Open Schooling system, which evolved out of the ODL system, to respond to challenging educational demand effectively, alternatively and as a complement/supplement to the formal school system. According to the Commonwealth of Learning (COL), Open Schooling involves "the physical separation of the school-level learner from the teacher, and the use of unconventional teaching methodologies, and information and communications technologies (ICTs) to bridge the separation and provide the education and training" (http://www.col.org/resources/publications/Pages/detail.aspx?PID=322).

The Open Schooling System, with its structural flexibilities related to place and time of learning, eligibility criteria, and the student’s choice in selecting a combination of subjects and scheme of examinations, has shown the potential for “reaching the unreached”, and “reaching all”. However, to meet country specific needs and demand, it is necessary to assess the viability of Open Schooling System in an attempt to answer one main question: Can the concept become a reality and should one proceed with it? With this rationale the situational analysis of the current school educational status in Afghanistan was undertaken to identify the challenges that are still there confronting the country.

Geography and Demography

Afghanistan is a land-locked country in south central Asia measuring 647,500 sq. km (250,001 sq. mi). It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and the east, Iran in the west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the north, and China in the far northeast. The topography of the country is a mix of central highlands and peripheral foothills and plains and it has an arid continental climate. Summers are dry and hot, while winters are cold with heavy snowfall in the highlands. Precipitation is low, although some areas in the east are affected by the monsoon. Decades of conflict have taken its toll on the environment, triggering deforestation, soil degradation, and depletion of ground water. Coupled with droughts and floods, there is a negative impact on the well-being and educational development of the country.

There is an estimated settled population of about 25.5 million, making Afghanistan the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world.

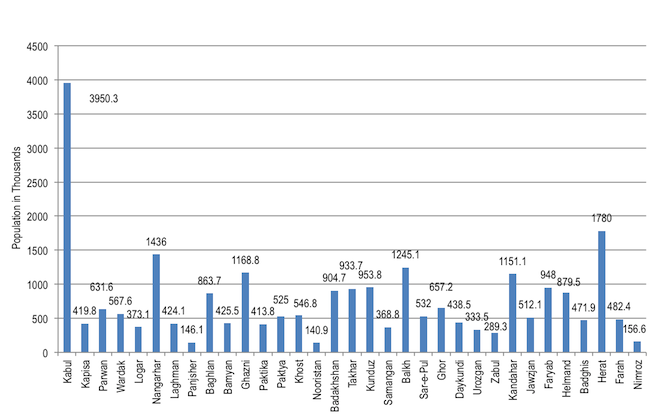

There are 34 provinces in the country, which are further divided into districts and there are a total of 398 districts. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the settled population in different provinces.

It can be seen that the population concentration is highest in Kabul, followed by Herat, Nangarhar, Balkh, Ghazni, and Kandahar. A great majority (76.18%) of this population is rural.

Fig. 1: Distribution of Settled Population in Different Provinces

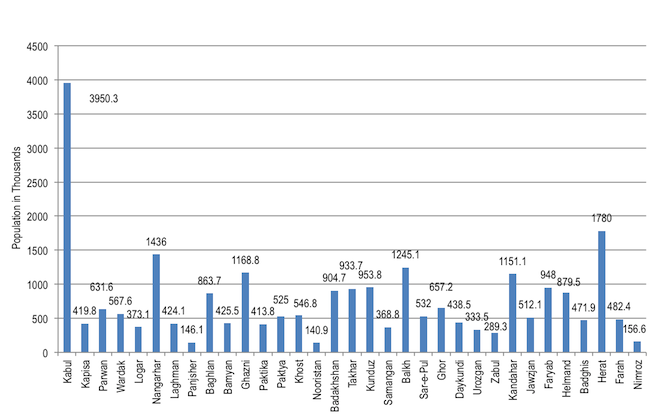

Fig. 2: Ethnicity Breakdown of the Population

The country is inhabited by different ethnic groups, such as the Pashtun, Hazara, Uzbek, Turkmen, Baloch and Hazara. The ethnicity breakdown of the population is shown in Figure 2. The official languages of the country are Pashto and Dari (Persian), although Persian is spoken by about half of the population and serves as the lingua franca for the majority. Pashto is spoken widely in the south, east and south west of the country. The Uzbek and Turkmen languages are spoken in parts of the north. Smaller groups throughout the country also speak more than 30 other languages and numerous dialects. Afghanistan, therefore, has a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual society.

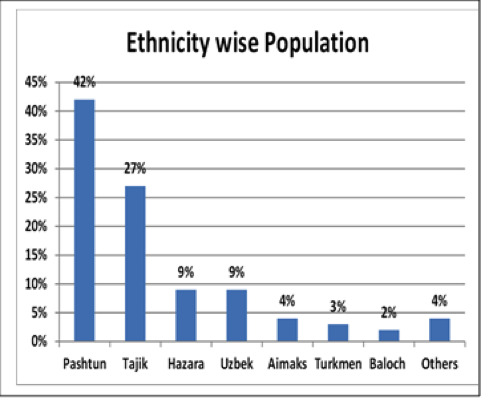

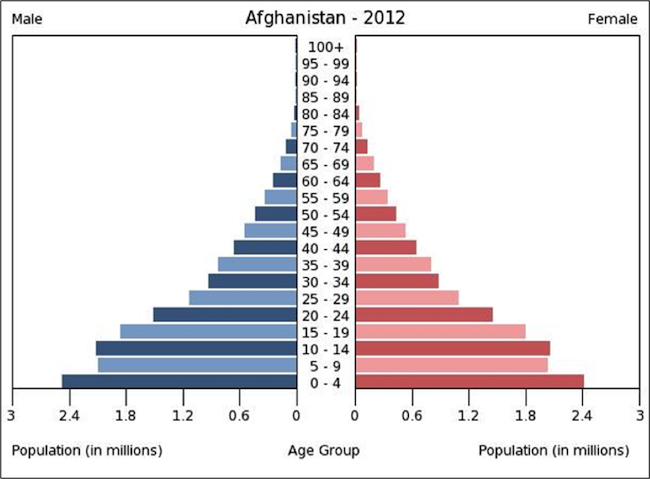

The Population Pyramid shown in Figure 3 illustrates the Age and Sex distribution for the year 2012. It is an expansive pyramid showing a broad base, indicating a high proportion of children, a rapid rate of population growth, and a low proportion of older people. The age structure is estimated as below:

The age structure of a population is a factor in a nation's key socioeconomic issues. Countries with young populations (a high percentage under age 15) need to invest more in schools, while countries with older populations (a high percentage aged 65 or over) need to invest more in the health sector. The age structure can also be used to help predict potential political issues. For example, the rapid growth of a young adult population unable to find employment can lead to unrest. In the case of Afghanistan the data shows that the country is young, with 64.8% of the population of both sexes being in the age range 0-24 years, and within this school-going age population the proportion in the age range 5-19 years is 39.2%. So Afghanistan’s population pyramid has the classic appearance of a country with a significant youth bulge, i.e., the proportion of young people is significantly large in comparison to other, older age groups.

Fig. 3: The Population Pyramid

(Source URL)

Thus, the geography and demography of Afghanistan poses the following challenges, which are difficult to control:

Educational Scenario

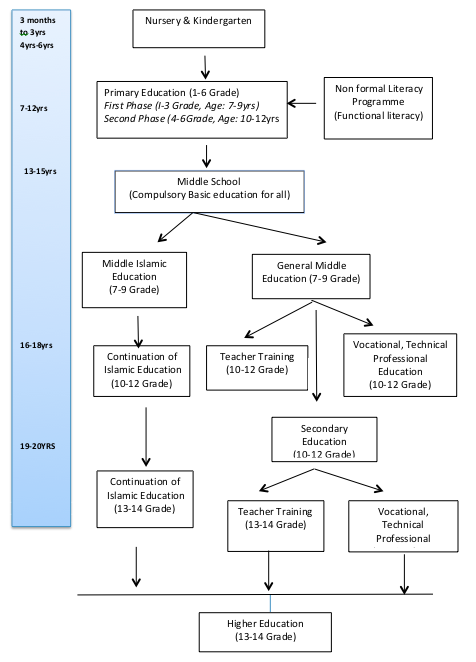

The structure of the education system in Afghanistan, as illustrated in Figure 4, Is comprised of three sub-sectors:

General Education covers primary, lower secondary and upper secondary levels of education from Grades 1 to 12 in state schools. The first six years of General Education is for primary schooling and the next three years, Grades 7-9, is for lower secondary. Together, the first nine years of schooling is considered as a complete cycle of basic education. Grades 10-12 constitute upper secondary education.

Fig. 4: Structure of the Education System in Afghanistan

To track progress on access, quality and equity indicators over time in Afghanistan‘s schools, data from the following were considered:

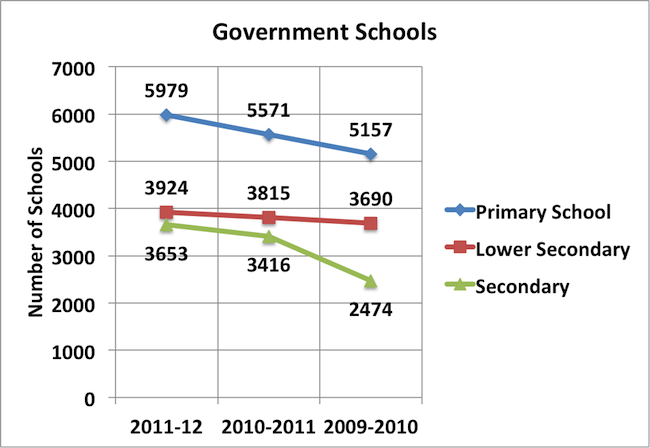

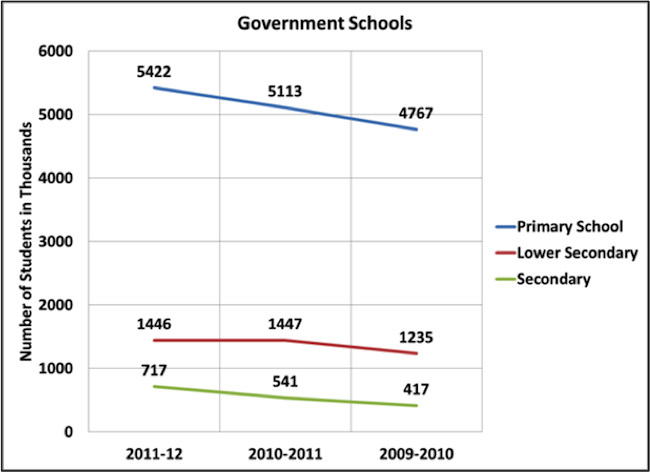

To facilitate access to education, state schools are being established every year. In the last three years the growth of primary, lower secondary and secondary schools is shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that more primary schools were established every year, compared to lower secondary and secondary schools. Consequently, there has been an increase in enrolment in different levels as shown in Figure 6.

Fig. 5: Number of Government Schools

Fig. 6: Total Enrolment in General Education in Government Schools

The data shows that the total enrolment of girls increased by 1% every year, being 37% of the total enrolment in 2009-10, 38% in 2010-11 and 39 % in 2011-12, respectively. In 2011, the picture of enrolment of girls in some provinces, as shown in Table 1, is rather dismal, being less than 30%. The percentage of female teachers has been around 31%. In provinces with a low percentage of girls enrolled, the percentage of female teachers is also less than 30%, as shown in Table 1. The student-teacher ratio in government General Education schools has been 44:1. Lack of female teachers is known to have an impact on the quality of education and school participation by girls.

Table 1. Enrolment of Girls and Female Teachers in General Education in Some Provinces.

Sr No. |

Province |

Girls Enrolment (%) |

Female Teachers (%) |

1. |

Paktika |

20 |

0 |

2. |

Paktya |

26 |

6 |

3. |

Khost |

26 |

4 |

4. |

Urozgan |

13 |

3 |

5. |

Zabul |

20 |

15 |

6. |

Kandahar |

26 |

16 |

7. |

Helmund |

20 |

19 |

8. |

Badghis |

27 |

12 |

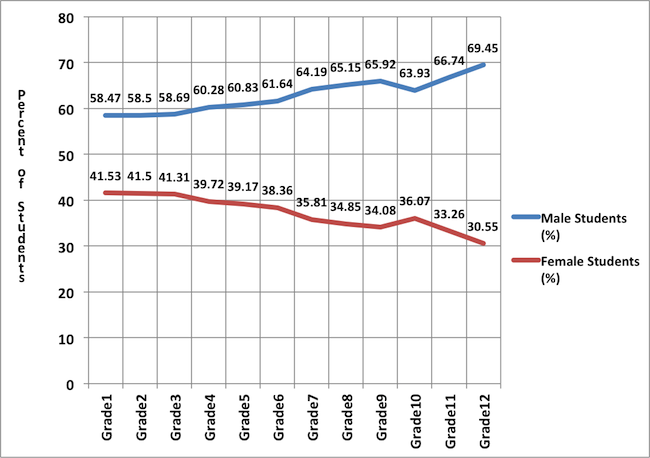

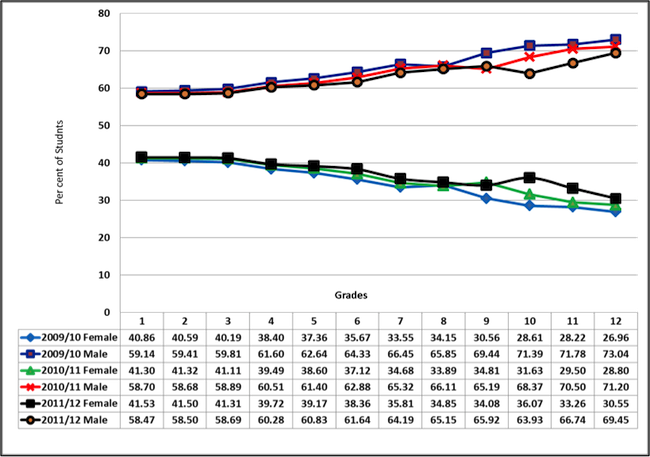

The grade and gender data for the year 2011-12 reveals that for the first three grades of primary school, enrolment numbers remain reasonably steady for both male and female students. Thereafter, the system is unable to retain female students. Compared to male students, there is a decline with attrition increasing at each grade. In other words, the gender gap increases with increasing grades, which is illustrated in Fig 7.

Fig. 7: Grade-wise and Sex-wise Enrolment in Government Schools, 2011

In 2011, there were 451,467 girls in Grade 1 and just 48,965 girls in Grade 12, that is, about 10% of females reach Grade 12. Inefficiencies in transition and completion are more marked for girls than for boys. The gap in primary enrolment between boys and girls has remained more or less constant, as shown in Figure 8, despite an overall increase in enrolment. At the secondary level, the numbers are far worse: older girls have particularly low rates of enrolment.

Fig. 8: Grade and Gender-Specific Enrolment, 2009-12

However, Figures 7 and 8 also show that, in Grade 10, there is a slight dip in the number of male students. Up to Grade 9, education is free and compulsory and is the transition stage from middle school to secondary level. Many male students may decide to discontinue at this stage. It is known that isolation, poor facilities and insecurity combine to limit access to school for rural children, particularly the girls.

It is known that when women typically have less access to and control over facilities, opportunities and resources, there is gender inequality. In terms of education this needs to be understood as the right to education [access and participation], as well as rights within education [gender-aware educational environments, processes, and outcomes], and rights through education [meaningful education outcomes that link education equality with wider processes of gender justice] (Wilson, 2003). Measuring meaningful progress towards the right to education is the first step in assessing progress towards gender equality. Also essential is assessing both quantitative and qualitative information and phenomena that underpin the rights of both men and women (Subrahmanian, 2003/04).

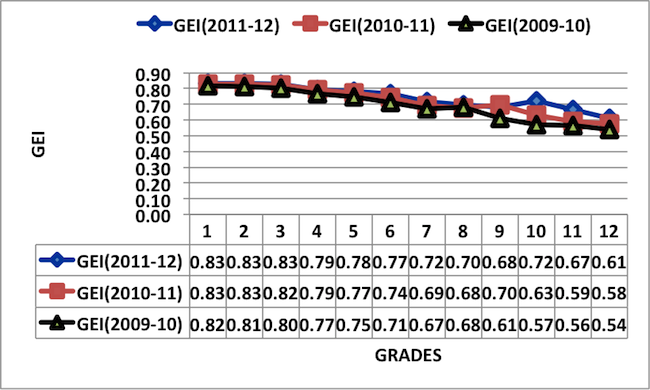

In the Human Development Index (HDI) of UNDP, adult literacy rates and combined primary, secondary and tertiary Gross Enrolment Ratios (GERs) are used as indicators. Since the share of enrolment at school education level is an element of HDI, one of the indicators that can be considered here is called Gender Equality Index (GEI), which is a comparison index.

The Gender Equality Index (GEI) can be considered as an indicator of the relationship between males and females in terms of educational access and participation at a given moment in time. Analysis of gender equality trends can then serve as an important signal of the probability that wider changes have taken place.

Fig. 9: Grade-specific Distribution of Gender Equality Index, 2009-12

In the context of Afghanistan, and considering the data for the last three years, Fig. 9 shows the Grade-specific distribution of the Gender Equality Index for the enrolment of male and female students in General Education. It is clear that for every grade the GEI remains more or less the same over the period 2009-12, indicating that, in spite of more schools, there has been no extensive change in the enrolment situation nor in girls' participation in schools. Although the number of boys and girls in a school is a key quantitative indicator of gender equality, there are also several other critical measures.

As international research suggests, the chances of acquiring and retaining literacy and numeracy are very limited without four to five years of good primary education, and many children fail to reach even minimum standards. Gaining access and staying in school is much more difficult for girls than it is for boys.

The Afghanistan Educational Sector Analysis 2010 report provides insight into the following two factors:

Another factor pointed out by this report is learning time, which has implications on the foundations of learning. The Education Law in Afghanistan mandates the Ministry of Education (MOE) to determine the beginning and the closing of the school year in different climatic zones and to set the number of weekly teaching hours. The following three factors appear to suggest that Afghanistan is at the lower end of the spectrum of learning time:

Even accepting that Afghanistan has a six-day school week there is clearly inadequate classroom learning time in general education schools in Afghanistan, which leads to a weak foundation for learning. As per NRVA (2007-2008), the major reasons for school-age boys and girls not attending schools is geographic distance, which is an access issue. Financial obstacles on the home front is another reason for boys not attending, indicating the existence of child labour. For girls cultural barriers are a major reason and reducing these would imply the need to build support in communities.

According to the MOE (Annual report, 2010), the major challenges in General Education are as follows:

Nevertheless, like any other country, Afghanistan also remains active in attempting to educate its citizens and, hence, as per the policy document NESP-II, the MOE has decreed that by 2014:

The issue is, therefore, one of coping with such educational challenges and meeting the set targets to accelerate the development of Afghanistan.

It is evident that to enrol the 10 million children into General Education by 2014 will require an expansion of capacity, i.e., more schools, more and better teachers, more learning materials and better support,which will undoubtedly put an enormous strain on the prevailing system that is already struggling to implement existing programmes. The formal schooling system as a single delivery system will not be able to realize the cherished hopes and aspirations of Afghanistan to universalise school education.

The challenges that the education sector in Afghanistan has to confront to achieve the education goals and targets set for 2014 and 2020 are daunting and immense. The country has to meet its constitutional commitments so that a literate and educated population underpins development and stability. Hence, exploration of strategies and new methods has become essential to cater to the multiplicity of learning needs beyond the formal system of education but parallel to it. Many believe that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to meet the demand and need for school education, particularly secondary education, without resorting to Open Schooling approaches. But why should a country have confidence in the open schooling system? Can Open Schooling meet the challenges a country faces?

Openness and flexibility are the two important features in Open Schooling. Withdrawing the barriers of space, place and pace of learning, Open Schooling has introduced a new dimension in education, which combines freedom to learn with functionality. It is apparent that the "open" in Open Schooling refers to the openness of the system; usually there are no rules dictating student ages, prerequisites, content of courses or number of courses in which learners must enrol. As a result, Open Schooling meets the needs of a broad range of learners:

Considering the educational challenges in Afghanistan and the unique features of Open schooling system, Table 2 following illustrates how to build confidence in establishing a new schooling system in the country.

Table 2. Educational Challenges versus the Unique Features of Open Schooling System.

Aspects |

Challenges in Afghanistan |

Can Open Schooling Cope with the Challenges? |

How? |

Topography |

|

P

P |

|

Demography Socioculture |

|

P

P |

|

Gender |

|

P

P

P |

|

Vulnerable groups |

|

P

P

P

P |

|

Infrastructure |

|

P

P

|

|

Resources |

|

P

P |

|

** In the case of NIOS, the largest open schooling open schooling system in the world, female students interest in general education is less than male students, in spite of flexibility and openness, while in vocational education, more female students take advantage of the system than male students. Hence, even if the gender gap is reduced it still needs to be equalised.

It is apparent that the inherent characteristics of an Open Schooling system, i.e., openness and flexibility, can deal with the educational challenges in Afghanistan, if implemented in the right spirit, that is, to provide a channel of educational opportunities to those who cannot and do not go to school.

The advantages of having Open Schooling system in Afghanistan are as follows:

With all conviction it can therefore be said, that an Open Schooling system in Afghanistan at the national level is feasible, and that it must be established with a vision, a mission and a set of objectives to meet challenges and provide educational opportunities to all.

Open Schooling is not only concerned with increasing access to schooling, but also with equalizing educational opportunities for citizens regardless of their geographic location or socio-economic background. Open schooling can be set up to reap the benefits of the economies of scale that distance education holds out as a possibility.

If a country like Afghanistan needs a population that is equipped to rise to the challenges that they it face in future, it will be difficult (if not impossible) for the country to meet the demand and need for school education on the scale envisaged without resorting to Open Schooling approaches. Open Schooling is the most feasible alternative that Afghanistan can have to address the challenges created by poverty, lack of social and educational infrastructures, cultural issues, insecurity and conflict, in order to fulfil its cherished educational goals.

Sushmita Mitra is the ex-Director (Student Support Services) National Institute of Open Schooling, India. E-mail: sushmitam@hotmail.com