VOL. 3, No. 1

This paper examines the place of public libraries in supporting distance learners in Makerere University, exploring the factors which affect utilisation of their services. The study adopted a survey design with 300 B.Ed. students, collecting data through focus group discussions, structured questionnaires and individual interviews.

Distance Education has gained a lot of popularity in many Ugandan institutions of higher learning mainly due to an explosive demand for higher education in traditional universities. The conventional system of education can no longer accommodate all aspirants to higher education and this development is, therefore, forcing many institutions of higher learning in Uganda to reposition themselves to become dual mode universities in order to satisfy the ensuing demand (Muyinda, 2012). However, being a relatively new mode of study the management of the teaching and learning processes still remains a challenge especially when it comes to provision of students support services such as off-campus library services. Nabushawo (2014) contends that relevant and quality study materials are the main teaching tool as well as the teacher for distance learners. This therefore suggests that supporting students is a very critical factor in influencing effective teaching and learning in Open and Distance Learning (ODL) programmes (Gil-Jaurena, 2014; Tait, 2003). Provision and access to library services by the ODL students at Makerere University is therefore central to ensuring quality education.

Given the context, this study has focused on the traditional distance education which still depends mainly on print-based study materials, with limited ICT integration in the teaching and learning processes.

ODL at Makerere University commenced in 1991 as the popularly named External Degree Programme (EDP) with the Bachelor of Education and Bachelor of Commerce External (Chick, 1990). These were later joined by the Bachelor of Science External, Bachelor of Agriculture and Rural Innovation, and Diploma in Youth in Development Work. The main objectives of starting external programmes in the Makerere University according to Aguti (2009, p. 219) were to:

The study package in the External Degree programmes at Makerere University includes study materials that are specially prepared to enhance independent study, and textbooks which are supplemented with two residential face-to-face tutorial sessions every semester at the main campus (DDE, 2006). During the face-to-face sessions students meet their administrators, tutors and peers for academic and administrative support. These students come from different parts of the country where they work and live and, therefore, remote support is very crucial in tutoring, access to library services, discussion groups with peers, etc. In this study, we will examine the role of public library services in supporting distance learners.

With non-traditional education having rapidly become a major element in higher education with expansion and an estimated enrolment of 15,000 students in Ugandan Universities (Siminyu, 2003; Matovu, 2012). There is, therefore, greater recognition of the need for library resources and services at locations other than main campuses to facilitate teaching and learning processes (ACRL, 2008). ODL students are entitled to library services and resources equivalent to those provided to students in conventional systems. However, according to Stephens (1996) traditional library services often fail to adapt to the needs of ODL learners, especially in dual mode universities. For instance, they fail to provide off-campus library services like region-wide borrowers’ cards and consortia membership between academic libraries. That is why Parnell (2002) contends that it may be unethical to offer a qualification to students without providing them with adequate resources for study. Hence, to protect the credibility of distance learning courses, adequate investment in library services is needed by university administrators, both on and off campus (ACRL, 2008). This situation may however be changing with the development of online studies and open educational resources which are readily available to the students as long as they are on the network. However, investment is still required in ICT infrastructure to enable students to access e-resources both on campus and off–campus.

Although other research has examined the role of libraries in ODL, especially those on campuses (Mayende & Obura, 2013; Kawalya, 2010; Middleton, 2005; Watson, 2003) there is little research on off-campus libraries and specifically the significance of public libraries in supporting ODL. Gopakumar and Baradol (2009) opines that the constraints that motivate students to opt for ODL are the same ones that limit their ability to use a centrally, often urban-located, library. They are likely to be working full time, and have family commitments, in addition to their student responsibilities; these obligations influence their access to study materials, both in time and space (Aguti, 2004). They, therefore, rely on library services at remote sites, interlibrary loans or travel to the main campus. ODL institutions commonly try to open study centers near to the students to offer academic support, which will often include library services. Library requirements for distance learners are threefold: the need for materials, facilities, and information and user services (Nicholas & Tomeo, 2005). Rather than being expected to go to the library whilst in ODL, the library should go to the students.

The main library service of emphasis to ODL students are the study materials provided by the tutor, and supplementary resource materials such as textbooks, journal articles from various data bases, CDs, audio tapes, video, internet services, e-books and online resources. In ODL, study materials take some of the role of the teacher in the classroom and, regardless of the technology used, their provision and accessibility are central to facilitate teaching and learning processes. Burgstahler (2002) says that the effectiveness of ODL is measured by the availability and accessibility of specially designed learning materials, with learners having enough time to use them to avoid surface learning. In other words involvement in ODL means acceptance of the principle that learners, regardless of their geographic location and obligations, have a right to all support services for the purpose of completing their programmes successfully.

At Makerere University, library services have traditionally been offered through a book bank system where core textbooks are acquired by university departments and study materials are produced specifically for distance learners. Library services, therefore, are offered through the departmental book bank at the main campus, in regional university study centre libraries, and sometimes in public libraries. According to Mayende and Obura (2013), the department has an estimated collection of 350 titles of study materials, with 28,000 copies lent out to students on the main campus and in collaborating libraries. As much as the department has tried to take its services nearer to the students, complaints have consistently come from students regarding the inadequacy of library services up-country. This is mainly because the good text books are in the main library at the main campus and, therefore, cannot be accessed easily by ODL students. The university has also subscribed to several online data bases but the ICT infrastructure is not available in the up-country centers and, therefore, ODL students cannot access these resources (Mayende & Obura, 2013).

According to Bbuye (2010) and Mayende and Obura (2013), with the exception of the upgraded centers of Fort Portal and Jinja, ODL library services in the up-country study centres of Makerere University in Uganda are neither equipped with substantial collections nor provide students with appropriate services. Alongside poor Internet access, and inadequate or outdated study materials, students struggle to get relevant resources to complete assignments and many do examinations without fsupplementary reading, which consequently affects the quality of not only their grades but also the education they receive. Lack of access to library services and related instructional resources is perceived to be an obstacle to starting or expanding ODL programmes (Burgstahler, 2002).

Given the above, many students have found support and assistance from public libraries across the country. According to Corbrett and Brown (2015) public libraries have always supported distance learners as members of the community, being entitled to support like anyone else. In an effort to support ODL students, Makerere University has been collaborating with public libraries to offer library services. Lebowitz (1997) adds that public libraries are often critical to the development of ODL as they enhance teaching and learning processes through provision of library services to the students. However, in Uganda, such support is not fully integrated in the university's provision and better coordination may help secure effective student support. This paper, therefore, examines the place of public libraries in supporting distance learners in Makerere University, Uganda.

In Uganda some public libraries have proven more effective in supporting learners due to their consistent distribution across the country, and the extent of services and facilities they can provide. They have regular opening hours, including weekends, reading space, a variety of reading materials (including research reports, government documents and reference books) and Internet facilities, which provide e-books and online resources. The Makerere University library collections are also accessible through its online catalogue, which provides Web-based access to a broad variety of electronic databases viewed as abstracts and full text. These however, are not accessible to most of the ODL students up-country (Mayende & Obura, 2013). Corbrett and Brown (2015) confirm that public libraries have always purchased databases, journal subscriptions or reference books specifically with students' needs in mind. However, they confess that there is a limit to which public libraries can support university students without better collaboration between library and the university.

As noted earlier, ODL students are unique and have different needs which cannot fit within the existing university infrastructure and policies (ACRL 2008). This, therefore, means that deliberate policies have to be made by the universities to support ODL. This is also echoed by Watson (2003) who says modalities and strategies have to be devised by librarians, distance educators and administrators to take library services to the students. Borrowing of learning materials should not be inhibited by lending restrictions and study materials should be provided in as many locations as possible (Aguti, 2004). Many institutions offering ODL collaborate with public libraries by linking students to their university libraries electronically and by providing deposit collections at public libraries remotely (Corbrett & Brown, 2015).

In this study, we examine the nature of support services offered by public libraries to Makerere University ODL students in Uganda. Our motives for such a study reflect a drive within the University to increase the quality of ODL education. That said, utilizing public libraries as facilitators to ODL may provide a way to support ODL across similar contexts, particularly in those where online access is low, as in rural communities. We focus in particular on the following research questions:

This study employed a survey research design which used both qualitative and quantitative approaches to data gathering and analysis. To attempt to make the study representative, data were collected in the four regions of Uganda (Central, East, North and West). Four public libraries were visited — one from each region. These libraries were selected purposefully to match those areas with the greatest concentration of ODL students. Cluster sampling was used to select 300 students out of 3500 in the B.Ed. programme offered through ODL in Makerere University. The clusters of B.Ed. students included 90 first-year and 210 third-year students, who were asked to share their experiences regarding student-support, and, specifically, library services up-country. The two groups of students were chosen to share their expectations (first-years) and experiences (third-years) in relation to library services in ODL. Thirty key informants were also purposively selected to participate in the study. These included seven librarians, five lecturers, ten students and six members of staff from the ODL Department.

Information from respondents was gathered using a structured questionnaire, interviews and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). FGDs were held in each of the public libraries visited and the purpose was to solicit in-depth information from a cross-section of key informants. An observation check list was also employed to establish the actual facilities available to students. For purposes of triangulation, relevant documentary evidence was used to support and validate information obtained using other techniques. Interview and focus-group dialogue was recorded, categorized, and thematically coded in order to draw conclusions. Some numerical data were also analyzed with descriptive statistics.

In this section, the findings of the study are presented in relation to the research questions.

Students across Uganda were asked to indicate the services and facilities available in public libraries which they had used to facilitate their learning. The details are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Services and Facilities Accessible in Public Libraries

Available Services and Facilities |

YES |

% |

NO |

% |

ODL Study materials |

126 |

42% |

174 |

58% |

Other Supplementary reading materials |

112 |

37% |

188 |

63% |

Computers and other Accessories |

198 |

66% |

102 |

34% |

Internet and online data bases |

223 |

74% |

77 |

26% |

Technical staff (Librarians and ICT) |

220 |

73% |

80 |

27% |

Reading Space |

189 |

63% |

111 |

37% |

Some of the factors raised in the interviews with students, librarians and programme administrators in relation to utilization of the resources are discussed below.

Results from the Table 1 show us that some students have been utilizing the services and facilities in the public libraries, especially the Internet and online databases (74%). They also benefited from technical staff (73%), reading space (63%) and study materials (42%). However, a large percentage said there are no study materials (58%) and supplementary reading materials (63%). Interviews with students who did not visit the library revealed that many students were not aware of the services and facilities available in the public libraries. These responses from students have been analyzed together with the observations and interviews carried out with the librarians and programme administrators, while examining the factors affecting the utilization of public libraries by distance learners of Makerere University.

Analysis of the students' responses from Table 1 show that a good number of students are not aware of the existence of the public libraries and the services therein and therefore made minimal use of them. For example 58% of them did not know that study materials had been deposited in the public libraries and 63% had no idea that they can obtain supplementary materials from the public libraries. This was very prominent in Northern and Eastern Uganda as librarians reported that students had not visited the library in the last four years. This was mainly attributed to breakdown in communication among students, programme administrators and public libraries. The librarian in Fort Portal said; “We have resources here which can be utilized by the ODL students but they do not come! The university should communicate to the students to come and utilise these facilities.”

There is a need to improve communication to students about the existence of public libraries so the resources can be utilised to full potential by ODL students. Emphasis should be given to communicating and maintaining contact with students through a variety of media, using available technologies like mobile phones, networks and systems (Muyinda, 2010). The relationship with other stakeholders like librarians should be nurtured as well to ensure a smooth running of activities by partner institutions. Middleton (2005) observes that if such relationships are not well handled, collaborations can be hindered by factors like inflexible organizational management structures and narrow administrative vision.

Presence of Study Materials

Results in Table 1 indicate that 42% of the students confirmed that ODL study materials were available in the public library, while 58% claimed they were absent. The quality of study materials available to the students is also important as ordinary textbooks may not facilitate learning. Students preferred if they were in a self-study interactive format whether they were print-based or technology mediated. Use of ordinary books and articles may turn out to be counterproductive, as students claim they are difficult to comprehend without the guidance of the tutors. Essentially, the students prefer the study materials that have been specially prepared for their learning, since they are easy to understand and have been prepared for that purpose. ACRL (2008) further advises that study materials should have sufficient quality, depth, quantity, scope, and currency to meet all students’ needs in fulfilling course assignments, meet teaching and research needs, and facilitate the acquisition of lifelong learning skills.

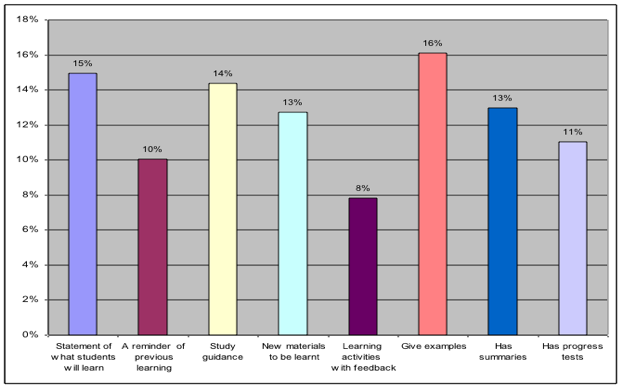

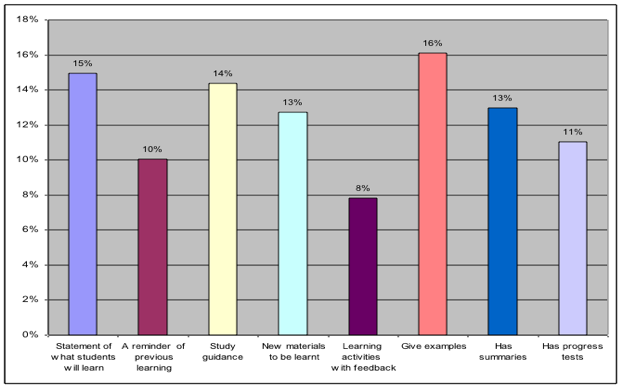

In this respect, students were further asked to indicate multiple responses whether the study materials given to them had interactive features to facilitate learning. The details of students' responses are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Interactive features in study materials

From students' responses, the major characteristic of the learning materials was to give examples (16%). The learning materials also contained statements of what students were to learn (15%), served as study guides (14%), and contained summaries (13%), among others. Usually, where study materials are not written in an ODL mode, the material should be accompanied by a study guide to facilitate learning. During the study, all the students interviewed reported that they are not given any study guides to accompany the study materials. In the absence of study guides, the students are left to use the study materials as they are and yet these are not interactive to facilitate learning.

In view of the challenges regarding the quality of study materials, programme administrators suggested the need for more facilitation to train tutors and writers in materials development so as to improve the quality.

Variety of Study Materials

The study found out that the reading materials in the public libraries were mainly print materials, as reported by 94% of first-year and 76% of the third-year students (Table 2). On the other hand the results in Table 2 below indicates minimal use of audio (5.6%), video (5.6%), and audio-visual materials (5.6 %). This is mainly attributed to inadequate resources both human and financial to produce these materials. According to administrators of the programme, the required expertise and infrastructure is not in place to facilitate production of these materials. The programmes therefore depend mainly on the print study materials which take the form of text books, readers, study guides, handouts and extracts from various literature sources and specially designed materials, written in a style appropriate to distance learners (Aguti, 2004). There is a danger, however, in relying on only print materials because according to Bates (1994), print promotes accumulation of facts and information but not critical thinking. The programme administrators are therefore encouraged to use blended methods of teaching materials to enhance acquisition of the relevant competencies.

Table 2: Variety of Study Materials Available in the Public Libraries

|

Year of Study |

||||

|

First |

Third |

|||

|

Frequency |

Percent |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Print Material |

Yes |

85 |

94.4 |

160 |

76.2 |

|

No |

5 |

5.6 |

50 |

23.8 |

Audio Material |

Yes |

5 |

5.6 |

53 |

25.2 |

|

No |

85 |

94.4 |

157 |

74.8 |

Video Material |

Yes |

5 |

5.6 |

5 |

2.4 |

|

No |

85 |

94.4 |

205 |

97.6 |

Audio Visual Material |

Yes |

5 |

5.6 |

24 |

11.4 |

|

No |

85 |

94.4 |

186 |

88.6 |

Availability of Supplementary Materials

The students (74%) who visited the public library also reported that the study materials deposited there are outdated and therefore not very helpful while doing their research. They however, applauded the library for providing a variety of references, from both the shelves and the Internet, which they have utilized as supplementary references.

In this respect, the librarians requested that the university should send them up to update study materials to facilitate learning.

Information Communication Technologies (ICTs)

New developments in ICT offer a lot to ODL in terms of information retrieval and access, interaction and collaboration. The Internet broadens the scope of ODL by extending the time and location boundaries in which courses can be delivered (Tan, Lin, Chu, & Liu, 2012). All the public libraries visited had ICT facilities like computers and the Internet, which provided opportunity for online research, as well as typing. The librarians also reported that through the national library board, they have subscribed to some online databases like EBSCO, Emerald and some African journals which are accessible by their readers.

Students who had visited the library (74%) confirmed that they had access to IT facilities, including the Internet. They appreciated electronic materials although they did not have access to the databases the university subscribes to because there is no arrangement by the university to have these accessed through the public libraries. The students using the library did have access to computers to do their in-depth research using online resources. However, Mayende and Obura, (2013) contend that with appropriate infrastructure in place, electronic delivery of information materials from the main campus to the public libraries is possible but only if the working relationship between library and university is streamlined.

Without free provision of ICT services, students suffered from financial hardship, which could form a barrier to participation. One B.Ed student who was not aware of the library services lamented: “We have been spending a lot of money in internet cafes to surf and do research when we could access the internet cheaply here!” This is a sign that students are not well informed of the resources available to them at these public libraries.

Librarianship

The public library had trained staff in the field of information science and competently served students. According to records from the public libraries website, all public libraries are being managed by trained librarians. The study also established from the libraries visited that the officers in charge had at least a diploma or degree in library and information science. This was also seen from the way study materials deposited for students were well organized on the shelves but staff complained that only a few students had actually borrowed books. They also indicated the poor reading culture among the students: “Our students do not have a reading culture; even the available resources are not fully utilized”.

Qualified personnel are very important because they can ably assist students to source the references and journal articles from the databases. In case of effective decentralization of library services including online materials, these staff could assist the students competently because of their familiarity with the software (Mayende & Obura, 2013). According to ACRL (2008), in some cases the collaborating institution must provide professional and support personnel with clearly defined responsibilities at the appropriate location(s) to attain the goals and objectives for library services in the distance learning programme.

Reading Space

The study found out that public libraries have ample reading space which ODL students utilized for their reading, with 63% of the students who have been visiting the public libraries reporting a conducive reading environment. Many of these students, as already noted, may not be able to read in their homes or where they work because of family or employment obligations. Many of them claim to do serious reading and studying only when they report for face-to-face tutorials on campus.

Remoteness from the Library

to the public library is also a factor that can affect its utilization. This is mainly a problem because they are all located in urban centres and some students find it difficult to reach them because of poor roads and poor transport. One B.Ed student said: “From my home to Lira town is about 85 miles and I use two taxis! I can only come to the public library if I am sure the study material I need is there.”

The fact that the university took steps to deposit study materials in public libraries for ODL students is evidence enough that the university was concerned about the need to support ODL students. What is therefore required of the university is to renew the contract so as to establish formal collaboration and facilitate smooth working relationships. Inter-library cooperation is not new in education and particularly in ODL. Morrissett and Baker (1993) contend that the backbone of ODL library services is embedded in cooperation of libraries at a local, national and international level. The study established that study materials in the public libraries are inadequate, outdated and do not comply with ODL standards of study materials (ACRL, 2008). As the university renews its commitment to work with the public libraries, up to date and relevant study materials should be deposited, preferably those written in an interactive manner to facilitate independent study. Similarly, given the evolution of ODL from first generation to, now, fifth generation, which is technology mediated, arrangements should be made so that the university can give public libraries access to its databases for ODL students to access e- resources wherever they are.

Noted further was that public libraries have been very supportive in offering library services to ODL students who visited them. However, they are not being utilized fully due to inadequate information about their locations and services. The programme administrators should therefore avail students with relevant and regular information about public libraries, their locations and the services available there. The students who visited the public libraries appreciated the conducive environment for reading, which was not available in the study centres. Students interviewed preferred the study materials deposited in the public libraries, rather than the centers, because of other added advantages like the Internet connection and the availability of supplementary reading materials from the libraries’ other collections. The Internet also enables students to access online databases and other open education resources, which enhanced students' research and knowledge base. The university should harness the working relationship it already has with public libraries so as to utilize their rich resources for students’ learning.

The university should also increase the allocation of funds towards ODL activities as well as continue lobbying the development partners to support the revamping of library services for ODL students. These funds can facilitate the equipping of ODL branch / partner libraries with relevant study materials to ensure adequacy and convenience. Relevant and up to date study materials need to be developed for students and supplementary reading materials bought or adapted. Similarly, to have students access on-line materials requires ICT infrastructure in place and, of course, qualified staff. Interviews with the ODL administrators revealed poor funding towards library services and specifically study materials' production for ODL, such as print study, audio and audiovisual materials, plus e–resources. These materials can be acquired through buying, making and adapting (Perraton, 1993). According to the findings from administrators, huge investment is required in developing study materials for distance learners in terms of acquiring qualified personnel to develop materials as well as the technology required for audio and audio-visual materials. One of the administrators said, “Study materials production is a process that requires huge funds because of the relatively long process involved right from course design, writing, editing, reviewing and finally publishing”.

The study established that, over ten years ago, the university signed a memorandum of understanding with public libraries to deposit some study materials in the libraries to be accessed and utilized by ODL students. This arrangement has been very effective in supporting ODL students because public libraries are widely spread across the country and almost all students can access them. Through this relationship, students have been able not only to access the study materials but also get access to other services in the public library. These include reading space, computers, Internet, and supplementary reading materials from the shelves and also online resources from the databases they subscribe to. However, the study also found out that the study materials deposited in these libraries are outdated and no longer very helpful to the students. This could have been because, over time, the working relationship between the two institutions has become weak, mainly due to a failure to renew the contract, making it difficult to deposit any further study materials at the public libraries. Students’ ignorance about the facilities and services at the public libraries may also be attributed to poor public relations or a breakdown in communication between the university staff and the students.

Authors

Harriet Mutambo Nabushawo is a Lecturer in the Department of Open and Distance Learning, School of Distance and Lifelong Learning. E-mail: hnabushawo@gmail.com

Jessica Norah Aguti is an Education Specialist, Teacher Education at Commonwealth of Learning (COL), Canada. E-mail: jaguti@col.org

Mark Winterbottom is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. E-mail: mw244@cam.ac.uk