2023 VOL. 10, No. 3

Abstract: This study explored learning which occurred when mature distance education students co-developed an open educational resource (OER) with their lecturers using Smith’s critical reflection as a method to guide reflection on their learning. This study is significant since student learning on the co-development of an open educational resource could not be found in the literature. Within an interpretative paradigm, we used questionnaires with mainly open-ended questions to determine a particular group of students’ learning. Findings indicate learning about themselves, their interactions, and their contexts. The study puts forward specific implications to improve future practices based on the findings. The specific contribution is that students who engage in critical self-reflection change their perspectives, allowing them to self-examine and reflect on future actions. This learning experience assists students, lecturers and institutions of higher education in their approach toward critical reflection and the co-development of OER.

Keywords: critical reflection, students as co-developers, Open Educational Resources, mature students.

To support mature students in achieving success, they require a self-directed learning environment that is supportive and hinged on the tenets of constructivism, where such students are offered opportunities to co-construct knowledge with their instructors. Such an environment should provide clear direction to help them explore new opportunities, while nurturing guidance is necessary to instil confidence in themselves to act autonomously. Additionally, critical reflection is crucial in this process, as it allows students to challenge their beliefs, assumptions, and perspectives on their learning, exposing them to various viewpoints. While the initial development of the OER in this study started with individual contributions, this approach allowed them as co-developers to collaboratively refine the OER by engaging in constructive criticism of each other's work. The diverse perspectives played a crucial role in improving the quality of the OER. Yamagata-Lynch et al. (2013) argue that critical reflection allows students to examine their expectations and ideas, thereby gaining confidence in their learning experiences. Further value of engaging in critical reflection is that it helps adult learners achieve personal and professional growth (Cranton, 2002).

Furthermore, Smith (2011) highlights the importance of critical reflection in assisting students to reflect on their learning within a particular discipline. She developed a critical reflection model for healthcare students, which supports their thinking, learning, and self-assessment in their social settings. By adapting Smith’s model (2011), we engaged participants in this study in critical reflection of their experiences as co-developers of an open education resource (OER). OER are open materials that are typically developed by lecturers, researchers, and institutions. These resources are enabled by information technologies offered freely for use by lecturers, teachers, students, and self-learners. OER are a relatively new phenomenon that is part of a larger trend towards openness in higher education, and they are available in the public domain and, in most cases, released under a licence for free use and adaption (Hilton, 2020).

The process of co-producing OER has become a new trend. It is in this light that Hodgkinson-Williams (2014) urges institutions to support lecturers and students to co-produce OER. Such co-creation efforts align with Mezirow’s (2007) disorienting dilemmas where mature students, after critical reflections and self-evaluation, bring the knowledge and experiences they have gained over time to bear to enrich the content they co-develop. The existing literature also shows that such activities promote social inclusion among graduate students while they reuse materials in future iterations (Andone et al., 2020; Hodgkinson-Williams & Paskevicius, 2012). Due to the overdependence on content from developed economies, Amiel (2013) asserts that co-creation of OER will reduce such situations and lead to the “advantage of the technical and legal affordances that have made sharing of knowledge relatively easy and the opportunity to develop and share local knowledge and indigenous ways of knowing” (p. 136).

From the foregoing, there is no shortage of studies on critical reflection and co-development of OER. However, what could not be found were studies about mature students’ critical reflection on their learning while acting as co-creators of an OER. The current study, therefore, aimed to examine mature students’ critical reflection on their learning while they acted as co-developers of an OER in open distance learning (ODL). As lecturers, we identified the need for a contextualised OER in a structured master’s in education programme and invited suitable students to develop the OER with us.

Based on the above, the study was guided by the following research question:

How does mature students' critical reflection as co-creators of an OER foreground their learning to improve future practices?

Merriam (2001) suggested that educators working with mature students should consider a holistic approach to addressing their needs. She contends that adults bring more to the learning setting than mechanical processing of information. Like earlier adult education philosophers (such as those of Knowles, 1980), we agree with Merriam (2001) and Mezirow (1997), arguing that adults bring a wealth of experiences, memories, emotions, and various ideas, which contribute to their understanding of the content. Furthermore, mature students often have a unique perspective on the subject matter based on their life experiences and work history. They can create new knowledge and understanding by sharing their insights and perspectives. The study of Hodgkinson-Williams and Paskevicius (2012) on the role of postgraduate students as co-creators of OER found that students had more experience with new mediating tools, alternative copyright rules, the composition of metadata linking materials to different platforms and sharing materials. They conclude that, amongst others, students developed a growing sense of agency and that it would be a pity not to use their knowledge and skills. Similarly, the study by Andone et al. (2020) found that students were surprised that they could co-create new OER with relative ease due to advanced applications and the ubiquity of mobile devices. The activity improved their digital lifelong learning abilities and inspired them to use OER in their quest for knowledge.

For the reasons mentioned, lecturers should involve mature students in their learning, as Cranton (2002) and Cox (2005) agree that reflection activities may serve as a good example of adult reflection on their learning. Such activities can lead to students making connections between new and existing knowledge and developing new insights for future use. Thus, involving students in the development of OER can promote learner-centred education, empower students, enhance collaboration, and improve the quality and relevance of educational materials. Also, it recognises students as active participants and co-creators of knowledge, fostering a more engaging and inclusive learning environment.

Reflecting on one's learning is a fundamental skill and an indispensable requirement in pursuing education. Therefore, the ability of scholars and students to engage in reflective activities is a crucial goal in higher education (Alt et al., 2022). Denton (2018) defines reflection as a formative self-assessment necessary in modern higher education settings, as the results of the exercise are used to improve practice. Reflection allows students to reconsider and reinterpret the situation in a way that brings clarity or new understanding, potentially leading to more effective decision-making in future practice. As further noted by Alt et al. (2022), reflection promotes higher-order thinking skills in higher education. In addition, reflection through self-assessment provides opportunities for students to express themselves freely and reflect on their beliefs, values, experiences, and assumptions that influence their learning, development and progress over time (Wallin & Adawi, 2018).

Related to our study, Klar et al. (2021) note that reflection is the conscious act of thinking back on a prior occurrence to conceptualise an issue from different angles. During reflection, participants in the current study engaged in thinking and analysis to better understand what they had learned. This involved examining the content from various viewpoints to gain insights and develop a broader understanding of their learning by critically analysing and re-evaluating the subject thoughtfully. As participants reflect on their experiences from different angles and learn from each other through peer cooperation, they become more effective and capable (Tan, 2021).

In describing reflective practice, Mezirow (1990) argues that there is more to reflection than thinking about one’s experiences, suggesting that critical reflection involves critique of current assumptions to improve future practices. Therefore, critical reflection is crucial in the cooperative creation of OER documents as it aids co-authors in rigorously evaluating information, challenging presumptions, identifying gaps, enhancing clarity, encouraging innovation, ensuring inclusivity, and continuously improving the resource (Kahn & Anderson, 2019). Hickson (2011) argues that critical reflection requires understanding of one's experiences in a specific social context and how this knowledge can be used in future practices. Through deliberate and introspective reflection, adults carefully analyse new information in relation to their existing perspectives, thus undergoing transformative learning experiences (York et al., 2016).

Transformational learning theory posits that adult students experience a disorienting dilemma and engage in critical self-reflection, leading to an evolution of their perspectives, where they will self-examine and reflect on future learning (Mezirow, 1978). Mezirow (2003) further summarises the link between transformative learning and critical reflection when he claims that critical reflection requires understanding the nature of reasons and their methods, logic and justification, while transformative learning is metacognitive reasoning involving these same understandings. In transformative learning, adult students always bring in a frame of reference that is important for the learning process (Mezirow, 1997). However, not all adult students’ experience may be relevant. Some of the experiences may be in conflict with the new experiences and there will be a need to unlearn and relearn as aspects of transformative learning.

Not everyone, though, agrees that critical reflection is a desirable activity. For example, Hickson (2011) notes that the term ‘critical’ might focus on the negative aspect of an experience, while Fook (2010) argues that critical reflection can be seen as a Western-orientated activity. Further critique notes a lack of research on the effectiveness, outcomes, and different methods and processes of reflection (White et al., 2006). However, as Fook (2010) argues, if researchers are aware of the critique, it puts them in a better position to incorporate critical reflection in a meaningful manner to fulfil its purpose. In light of the foregoing, the current carefully planned research was executed meaningfully as it aimed to determine mature students' critical reflection as co-creators of an OER to determine their learning and was supported by a specific critical reflection model.

Smith (2011) cautions that students often tend to be critical of their own performance and that critical reflection can become inward-looking and dominate the work itself. For this reason, she proposes that critical reflection should involve decentring oneself (based on the work of Bolam et al., 2003) and stepping back from one’s own practices. She developed a model for her healthcare students and argues that the model is broad enough to provide for different levels and techniques of critical reflection (Smith, 2011).

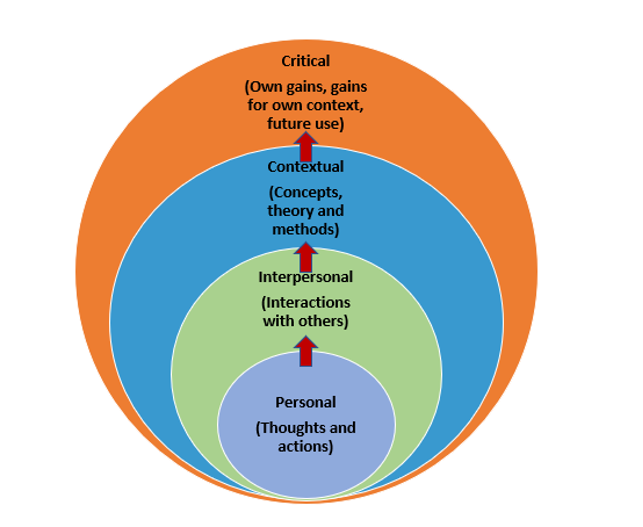

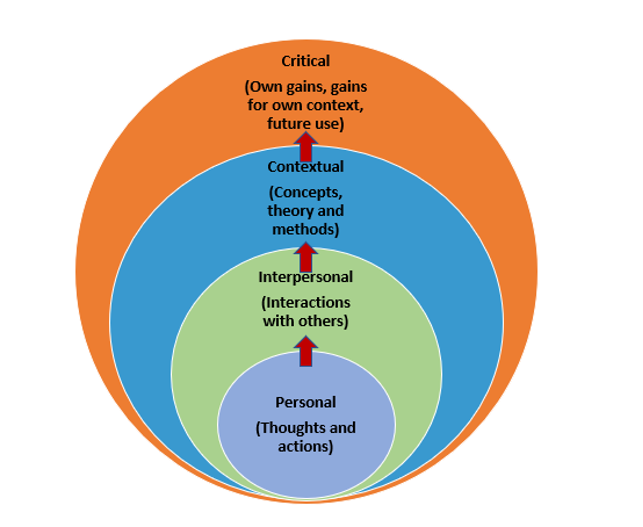

We found this description and the model applicable to our context, although we acknowledge that different models and typologies for systematic reflection in education exist (e.g., Valli, 1997; Jay & Johnson, 2002). We used Smith’s reflection model as our conceptual framework to guide this research. However, in line with Mezirow’s argument that transformative learning involves a critique of current assumptions to improve future practices, we adapted Smith’s original content in the outer circle to include reflection on own gains, gains for own context, and insights for future use. The adapted model is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Drawing from the literature, Smith (2011) identified the above four interrelated levels of critical reflection, which are discussed below.

The first level, personal reflection, involves one’s own perceptions. It has been described by authors such as Larivee (2008) as feelings and mood, agenda, self-awareness, and the ability to present oneself. It involves the evaluation of one's own learning experiences, thoughts, and actions to gain deeper insights and understanding. It requires students to think critically about what they have learnt and how it was learned. Personal reflection encourages individuals to engage in metacognition, which is thinking about one's own thinking, and promotes a deeper level of self-awareness, self-regulation, and continuous learning (York et al., 2016). Through personal reflection, students can analyse their strengths and weaknesses, explore their values, beliefs, and assumptions, and consider how these factors influence their learning and decision-making processes.

In addition, personal reflection allows students to take ownership of their learning and become active participants in the educational process. It helps them develop a sense of responsibility, self-direction, and accountability for their learning outcomes. In this sense, Chang (2019) argues that experiences can be related to a broader perspective through personal reflection, resulting in learning.

Interpersonal reflection, Smith’s second level, focuses on those central to a particular activity. It involves reflecting on one's own behaviours, emotions, and thoughts in relation to how they impact and are influenced by others. Smith (2011) indicates that this level includes the group dynamics and teamwork that influence decision-making. Interpersonal reflection can help students become self-directed by taking control of their learning and enabling them to recognise and negotiate complex theoretical, practical and professional issues for themselves. This level of reflection often occurs in social contexts such as collaborative activities, in this case, the co-development of an OER. It encourages individuals to consider their own perspectives and experiences, as well as those of others involved in the process. It involves self-awareness, empathy, and a willingness to critically examine their experiences and their effects on interpersonal dynamics. In this regard, Nilsson et al. (2017) agree that sharing experiences and learning from others creates connections and a sense of safety and belonging and can provide social support. Interpersonal reflection can be valuable for mature students as it helps them develop social and emotional skills and promotes teamwork and collaboration.

Contextual reflection, the third level of Smith’s critical reflection model, involves articulating the knowledge structures that are being used and asking what would happen if different knowledge frameworks were used. It refers to the different concepts, theories, and methods informing and influencing practice (Johns, 2004). It refers to various concepts that could have influenced theory and practice and how notions of theory have influenced practice (Smith, 2011). When engaged in contextual reflection, individuals can reflect on the theoretical frameworks, models, or concepts that inform their understanding within a specific context. This form of reflection involves considering how theories or concepts apply to the context at hand and exploring their strengths, limitations, and relevance (York, et al., 2016). By considering the theoretical underpinnings, they gain insights into the larger systems, structures, or ideas that influence their experiences and actions.

The fourth level of Smith’s model refers to critical thinking, with reference to political, ethical and social contexts to fit the context. However, because we did not focus on these aspects in this study, we adapted this domain to align with the Mezirow (1990) and Fook (2010) notion of critique of current ODL assumptions to improve future practices. We found this more applicable to the context of the current study, as we were interested in students' critical reflection as co-creators of an OER, foregrounding their learning, to improve future practices. Critical reflection as a theoretical construct and reflective practice are central to Mezirow’s transformative learning theory (Taylor, 2017). Although Smith (2011) argues that critical reflection on this level involves 'what' questions, we also focused on 'why' and 'how' questions, as they allow students to move beyond surface-level observations and reflect on the complexities of a situation. It helps to question dominant narratives and assumptions and explore alternative perspectives. Moreover, critical reflection can drive individuals towards action, prompting them to consider alternatives for change and improvement based on their insights. Therefore, critical reflection stimulates students to question their philosophies and beliefs and to connect theory and practice to solve problems (Chang, 2019).

We believe that moving through these four levels of reflection will assist mature students to start with the self before reflecting on their learning with others and the influence that interaction with lecturers and fellow students or others might have had on their learning. It was also necessary to find students’ reflections on their learning about theories, concepts, and methods. Lastly, in accordance with the literature on critical thinking and transformative learning, the students had to reflect on what they gained, why they perceived this as important and how their acquired knowledge will influence them, their context, and future learning.

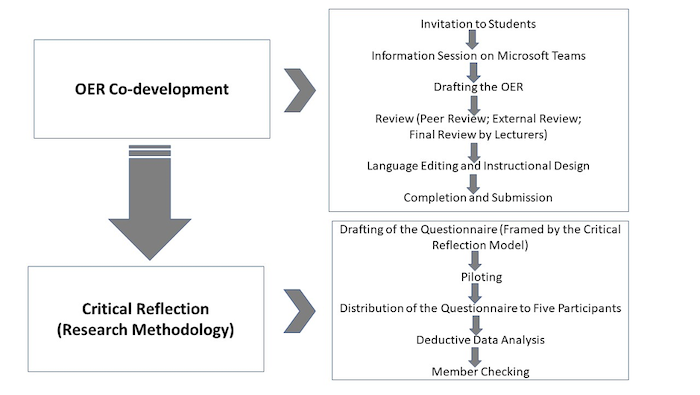

This paper is based on critical reflection on the OER development, based on the content of a structured master's programme at a South African Open and Distance Learning (ODL) university. The two lecturers, as the leading authors of this paper, are responsible for teaching four modules of this programme. They took the initiative to collaborate with students to create an OER using their lecture notes and student assignments. The students were invited via email to participate in the co-creation process and had the opportunity to decide on the themes they would like to cover within the broader topics provided. A Microsoft Teams meeting was conducted to further discuss the project with those who accepted the invitation. Students, as authors, had four weeks to draft their respective OER units. The lecturers took the lead by each completing a theme that served as examples for students to follow. The next step was for students to read each other’s drafts and to add comments for consideration and improvement. The students preferred communication via email and all students and lecturers were included in the communication. The drafts went through three rounds of peer review, during which mainly students were involved. Although they were initially reluctant to add comments to each other’s work, they showed more confidence as the process developed. The comments were mainly related to improving the content, while some were technical in nature. After the internal review process, we sent the draft document to an OER expert for external review, followed by a final review by the lecturers. In this process, students and staff negotiate meaning and control, but lecturers still take ownership of quality control and other aspects of the curriculum, which is in line with Lubicz-Nawrocka’s (2019) description of staff and student co-creation of the curriculum. After the peer review process was completed, the OER was sent for editing and instructional design.

In this study, the initial invitation was extended to six students, of whom five accepted the invitation to participate. The sample size consisted of five participants who completed the Master of Education programme. The sample included a representation of both genders, with three males and two females. These individuals were purposively selected from the 2021 student cohorts based on their academic performance in the four modules, which limited the selection to only the six best performing students. These students were selected because they demonstrated the ability to grasp and apply complex concepts effectively, which was crucial in creating quality Open Educational Resources (OER). Their strong academic performance suggested that they may have a deep understanding of the module content, which makes them better equipped to contribute to the development of Open Educational Resources. Due to their experience as students who completed their modules, they all contributed a unit based on the content of the module, and their contributions were comparable with respect to content, length, and quality.

This case study used a qualitative research approach to collect in-depth and detailed data within an interpretive paradigm (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) to interpret student learning after completing an OER. The empirical research process involved the development of a questionnaire based on the Smith (2011) model. To ensure the trustworthiness of the questionnaire, we conducted a pilot test involving a participant who was not involved in the study (Creswell, 2016). The open-ended questionnaire was administered on Google Forms to collect data (Braun & Clarke, 2019). Reflective questions included personal, interpersonal, contextual and critical reflections. Participants were given a two-week time frame to complete the questionnaire. This instrument was deliberately chosen. Firstly, reading the questions and having to respond in writing gave participants the opportunity to provide in-depth answers. Secondly, we wanted to provide students with the opportunity for honest reflection without the influence of lecturers or feeling an obligation to provide the answers we were looking for. Participants were ensured that their responses were anonymous. However, we acknowledge that because participants provided anonymous responses, data analysis did not allow for providing context and exploring how past experiences and personal positioning of individuals related to their reflections on the process. Thematic analysis was used following a deductive approach to analyse the data (Braun & Clarke, 2019). The themes or codes were derived from the critical reflection model, serving as a pre-established set of categories to apply to the data. The data were transcribed, anonymised, and organised for analysis. The coding process entailed using the pre-established themes for the data, with adaptations made as necessary to capture nuances and variations (Creswell, 2016). The analysis revealed themes supported by quotations and examples from the data (Braun & Clarke, 2019). We interpreted these themes within the context of the critical reflection model, drawing connections to existing literature, and providing insights into the research question (Creswell, 2016).

This study conducted member checking by sharing the research findings and interpretations with the participants. This allowed them to verify the accuracy of the data collected and provide feedback on the interpretations (Lincoln et al., 2011). By involving the students in this way, they also became co-researchers and co-authors, as they were involved in decisions when finalising the paper. Several authors have written on students as co-researchers and have reported on the benefits to both students and faculty. Although the way scholars write about students as co-researchers is often vague and can refer to any activity that involves students in the research process (Dollinger et al., 2022), we believe that involving students as co-developers of the OER as well as the critical reflection process and involving them as co-researchers added value to this paper. Their roles were clear from the beginning.

Ethical approval was obtained for this study (certificate number: 2022/10/12/1131109/25/AM).

Figure 2 below depicts this study's OER development and research processes.

Participants in this study had experience in higher education. Their experiences as distance education students varied between two and fifteen years. Responding to a question about their experience of using or developing OERs, only one participant indicated experience of OER development, while the others had only used them during their studies in the master’s programme.

In line with the conceptual framework of this study, four themes emerged and will be discussed next:

This section of the questionnaire focused on evaluating the participants’ own learning experiences, thoughts and actions to gain deeper insights and understanding of their experiences and had three questions. The first question asked students why they decided to be part of the co-development process. Although all participants were invited, participation was voluntary and there was no apparent benefit. Answers varied, and while two participants indicated that they intended to use OER in their own teaching, the others said that they wanted to share their knowledge, work closely with others, and make a contribution to the field.

As an example, a participant stated:

I want to develop as a researcher and share the knowledge acquired in the ODL space. And work closely with experienced mentors and colleagues.

Participants’ responses revealed the desire not only to develop themselves but also to learn from others. The notion is confirmed by Hodgkinson-Williams, and Paskevicius (2012), stating that postgraduate students as co-developers of an OER provided evidence that they were committed to sharing the materials they developed with others in their communities.

Participants were asked about their chosen topics for the OER, allowing them to reflect on their choices. As reasons, they indicated that they were either familiar with or interested in the topic and shared a desire to contribute to the body of knowledge. One participant linked the choice of the topic to the assignment for the master's programme, indicating that s/he chose the topic because the topic was well understood. The responses showed that participants were confident about their chosen topics and provided clear reasons for their choices.

The last question under this theme referred to challenges that participants experienced while involved in the co-development process. Three participants revealed that lack of time was their biggest challenge. This response was not surprising since all participants were teaching full-time. One of the participants, though, stated that s/he did not experience challenges, and the fifth participant indicated a few different challenges from the rest by stating that:

There was a need to read widely, and I had to set aside time to read before developing my sections. I was also not clear about what an OER looks like, and I had to seek the assistance of the project coordinators.

This reflection shows that lecturers cannot assume that students are familiar with OER and how to develop them. Despite our introductory online meetings as lecturers and researchers with the participants, the information and guidance were insufficient for this participant. This reflection was essential and shows that all involved in developing OER need sufficient knowledge and training.

The second section covered reflection on collaboration, background, and experiences with others involved in the process, and had three questions.

Participants were asked how their disciplinary background had influenced their choice of topic. In their responses, all participants agreed that their discipline influenced their choice. In this regard, a participant wrote:

It [my disciplinary background] was my main guide in contributing. I wrote about what I know and use daily.

The responses were important because they confirmed that participants were familiar with the contents and could confidently reflect on their contributions. They also brought a wealth of experiences, memories, knowledge and various ideas contributing to their understanding of the content, as confirmed by Merriam (2001). The fact that they could choose the topics for the OER also assisted in the sense that they could choose a topic they felt they were familiar with.

Participants were asked to reflect on their collaborators in the co-development process. In their responses, participants referred to their lecturers but indicated different levels of collaboration and support. While some indicated a substantial amount of support by stating that the support “greatly aided me in my understanding of what [was] needed” and “the feedback helped me to improve my writing and better package my ideas”, others were more independent and self-directed, adding that “I wrote the section alone, but the initiators of the publication always provided support and updates from revisions”. Here it is interesting to note that even though participants collaborated as students in their studies, they did not do so in developing the OER, and all chose to work on their own topics. Because the lecturers sent the draft OER to all for their input and encouraged them to add comments to all sections for peer-review and quality assurance purposes, a question was added to determine their experiences. The responses indicated that they added comments on different sections of the OER. While some acknowledged that they only made technical changes and added suggestions to the reference list, formatting and consistency in the OER, others indicated that they commented on the content. As an example, a participant stated that:

I read through other co-developers’ work and gave suggestions to add more literature and also suggested sub-sections that could be included in the particular topic.

Another participant added:

Yes, I did make some changes to the document, and the one that immediately comes to mind is the summary of learning theories – specifically constructivism, which I revised and provided feedback on.

From the responses, it is clear that participants claimed collective ownership in this collaborative initiative and showed student agency, an aspect Hodgkinson-Williams and Paskevicius (2012) found necessary in making decisions when students had to rework and improve the OER. Students were able to be active contributors to the OER and their own learning.

This section covered the theories, concepts, and methods contributing to students’ learning and had five questions. The first question asked about the influence of different theories or authors on the development of the OER. While two responses referred to different authoritative authors who are experts in ODL without mentioning specific names, the others were very specific, referring to distance education theories and learning theories that have influenced their learning, while another participant mentioned concepts she learned from content about the use of technology, as stated by several authoritative authors in the field. This reflection confirms that participants could reflect on their learning in the context of ODL, acknowledging some key theories and concepts that have informed their practice (Johns, 2004).

In the initial stages of the OER development process, all participants, as authors, were advised to use the content of their written assessments. The reason for the encouragement was threefold: 1) the relevance of their assessment content to the OER topics; 2) not to burden authors with more work than needed; and 3) the fact that, as students, they had submitted quality work and received high marks. Butcher (2015), in a basic guide for OER, supports using student assignments as OER and indicates that, in general, not much additional work is needed to publish them under an open licence. From the responses, it seemed that all used the content of their assessments but had to read further to add additional content.

For example, one participant said:

Yes, I used my assignment content, but I had to review the literature to support the elements of the theory I used and enrich my section.

Another participant added content from practical experience at the workplace and stated:

Some of the information I used for the content was practical information I learned while participating in strategic planning at my place of employment.These reflections show that although participants could use their assignments for the OER, they thought about the content and took responsibility for adapting or improving it to suit a different context.

The next question wanted participants’ opinions on their contribution to existing knowledge or practice in ODL. All participants believed that their contributions would add value. Although their responses did not come as a surprise, it was interesting that not all had the same reasons. For example, one participant stated that the context they brought to the OER would add specific value. At the same time, another referred to the value that the work would add to future groups of master's students. Furthermore, participants referred to the value the OER might have for ODL institutions, for example, by stating that:

It won't just help the ODL students who are pursuing a master's degree; in my opinion, it can also help ODL organisations how to manage their strategic planning.

The last question referred to challenges related to the adaption of the OER to a broader audience. From the responses, participants had no challenges in adapting their topics to a broader audience. They indicated that although they wrote from a specific context, the content would be applicable to different contexts. Additionally, they indicated that the OER could easily be adapted to different contexts. As an example, a participant stated:

I had no problems because I addressed the chosen topic using my experience working for my institution and my experience as a registered student. Additionally, I think my theme will apply to various organisations and students from outside this specific university.

Student reflection indicated that they were aware of the context they needed to address, and they could remove specific information that they did not find to be applicable. Since the purpose of this OER was to create contextualised content, this was a significant reflection.

This theme showed participants’ ability to move beyond obvious observations and reflect on the complexities of a situation. On this level, reflections are based on “how” and “why” questions; therefore, driving individuals towards action, prompting them to consider alternatives for change and improvement based on their insights. The theme had four questions. The first question referred to participants’ most valuable insights in the OER co-development process. Interestingly, most participants (four out of the five) indicated collaboration and the lessons and insights from others. As an example, one participant said:

Collaboration with others as we were able to work together and share ideas on each other's work and advice accordingly.

Another stated:

I realized how much we all learned from each other in different ways and how each of us focused on different topics in the same subject.

The reflection of participants confirms the collaborative nature of OER planning and development. It addresses earlier recommendations for more research on how collaborations can be beneficial and enhance the development of OER (DeRosa & Jhangiani, 2017, Brown & Croft, 2020; Van den Berg & Du-Toit-Brits, 2023).

Participants were asked to indicate who they thought would benefit the most from this OER. Here, all participants referred to either students or lecturers. What was interesting, though, is that although some participants referred to students and lecturers in general, others were more specific by referring to the lecturers and students in their own teaching contexts. For example, a participant said:

All students in my university, as it is a dual mode [institution], but those in the distance education mode will be the greatest beneficiaries.

Another one confirmed that they considered the OER useful:

Mostly my students and colleagues, but anyone who would like to know more about ODL theory and practice will benefit.

The third question sought to explore if participants, from their experience, would consider developing an OER in future. As a follow-up question, it asked what they would do differently if they had to develop an OER. In their reflection, all participants agreed that they would consider developing an OER, mostly because OER are in line with “where the world is heading” and are cost-effective. Some said they would “definitely” create an OER, confirming that reflection has the potential to drive individuals to action. The different approaches they indicated were working “closely with colleagues at my institution” and “collaborating more with the co-authors and giving more input on their work”, emphasising collaboration and better navigation of the OER. These suggestions for improvements in the OER development process assume that they have critically assessed their own actions, which is an integral part of their learning. Through deliberate and introspective reflection, they proposed different future approaches.

Lastly, participants were asked how the co-development process changed their views of OER. This reflection refers to critical self-reflection on practice, allowing participants to think about their perspectives, where they could self-observe and reflect on future learning (Mezirow, 1978). Participants referred to the role of the OER in the field of ODL as well as openness and access to knowledge in the field. As an example, a participant stated:

OERs provide access to educational material, allowing flexibility as I can adapt them accordingly.

Another participant referred to the co-development of the process by stating that:

Having worked on this project, I now believe it is feasible to develop OER with students and lecturers and see it through to completion. If you work on a project, it must have deadlines and a team leader to move forward and accomplish its objectives.

This response allowed for reflection on the value of the knowledge and skills they gained.

This study dealt with mature students' critical reflection as co-creators of an OER, foregrounding their learning to improve future practices. Findings indicate learning about themselves, their interactions, and their contexts. These findings have specific implications for practice. First, when students are involved in an OER co-development process, they are able to contribute to the body of knowledge in the field of their studies. Students not only learned to work collaboratively as a team and critically reflect on their experiences but they also learned the art of developing resource material that could be useful to others. Lecturers should consider including students when developing OER or related study materials. By doing so, both lecturers and students will benefit from the wealth of knowledge and experience of the students. Second, involving mature students in the development process assists them in their professional development, as they can use this practice in their own contexts. Third, students should be allowed to collaborate in OER development processes, as the findings of this study revealed that they found collaboration with others to be the most valuable aspect of the OER co-development process. Fourth, students should be allowed to critically reflect on their own learning, as it gives them insight into what they have learnt and how their learning has transformed their perspectives and future practices. This practice applies not only to mature students but to all levels of study. Lastly, involving students as co-researchers develops them as researchers to build capacity in research and contribute to students’ professional development. The participating students were able to develop their research skills as postgraduate students who were able to work in a team, and work cooperatively to develop scholarly material in the form of an OER.

As with all human endeavours, this study is not without limitations. The sample of five is deemed small, but since this was an in-depth study, it was deemed sufficient for the research. Also, involving participants in the ways indicated in this paper not only develops them in different ways but also assists lecturers and higher education institutions in their approach toward critical reflection and the co-development of OER. Ongoing research on how students can be involved in OER and related materials development and critically reflecting on their learning is needed to improve future practices.

Alt, D., Raichel, N., & Naamati-Schneider, L. (2022). Higher education students’ reflective journal writing and lifelong learning skills: Insights from an exploratory sequential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(1), 1-17. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707168

Amiel, T. (2013). Identifying barriers to the remix of translated open educational resources. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 14(1). http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1351/2428

Andone, D., Mihaescu, V., Vert, S., Ternauciuc, A., & Vasiu, R. (2020). Students as OERs (Open Educational Resources) co-creators. 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (pp. 34-38). IEEE. DOI: 10.1109/ICALT49669.2020.00017

Bolam, B., Gleeson, K., & Murphy, S. (2003) “Lay person” or “Health expert”? Exploring theoretical and practical aspects of reflexivity in qualitative health research. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(2), Art. 26.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589-597.

Brown, M., & Croft, B. (2020). Social annotation and an inclusive praxis for open pedagogy in the college classroom. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, (1), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.561

Butcher, N. (2015). A basic guide to open educational resources (OER). UNESCO and Commonwealth of Learning. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000215804

Chang, B. (2019). Reflection in learning. Online Learning, 23(1), 95-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i1.1447

Cox, E. (2005). Adult learners learning from experience: Using a reflective practice model to support work-based learning. Reflective Practice, 6(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940500300517

Cranton, P. (2002). Teaching for Transformation. In J.M. Ross-Gordon (Ed.), New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education: No. 93. Contemporary Viewpoints on Teaching Adults Effectively (pp. 63-71). Jossey-Bass.

Creswell, J.W. (2016). Reflections on the MMIRA The future of mixed methods task force report. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(3), 215-219. https://doi: 10.1177/1558689816650298

Creswell, J.W., & Creswell, J.D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

DeRosa, R., & Jhangiani, R. (2017). Open pedagogy. In E. Mays (Ed.), A guide to making open textbooks with students. The Rebus Community for Open Textbook Creation. https://press.rebus.community/makingopentextbookswithstudents/

Denton, A. (2018). The use of a reflective learning journal in an introductory statistics course. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 17(1), 84–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725717728676

Dollinger, M., Tai, J., Jorre St Jorre, T., Ajjawi, R., Krattli, S., Prezioso, D., & McCarthy, D. (2022). Student partners as co-contributors in research: A collective autoethnographic account. Higher Education Research & Development, 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2139359

Fook, J. (2010). Beyond reflective practice: Reworking the ‘critical’ in critical reflection. In H. Bradbury, N. Frost, S. Kilminster, & M. Zukas (Eds.), Beyond reflective practice approaches to professional lifelong learning (pp. 37–51). Routledge.

Hickson, H. (2011) Critical reflection: reflecting on learning to be reflective. Reflective Practice, 12(6), 829-839. DOI: 10.1080/14623943.2011.616687

Hilton III, J. (2020). Open educational resources, student efficacy, and user perceptions: A synthesis of research published between 2015 and 2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 853-876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09700-4

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. (2014). Degrees of ease: Adoption of OER, open textbooks and MOOCs in the Global South. OER Asia Symposium.

Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Paskevicius, M. (2012). The role of postgraduate students in co-authoring open educational resources to promote social inclusion: A case study at the University of Cape Town. Distance Education, 33(2), 253-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2012.692052

Jay, J.K., & Johnson, K.L. (2002). Capturing complexity: A typology of reflective practice for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 73-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00051-8

Johns, C. (2004). Becoming a reflective practitioner (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

Kahn, P., & Anderson, L., (2019). Developing your teaching: Towards excellence. Routledge.

Klar, H.W., Huggins, K.S., & Andreoli, P.M. (2021). Coaching, professional community, and continuous improvement: Rural school leader and coach development in a research practice partnership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1869311

Knowles, M.S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (2nd ed.). Cambridge Books.

Larivee, B. (2008). Development of a tool to assess teachers’ level of reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 9(3) 341-360. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623940802207451

Lincoln, Y.S., Lynham, S.A., & Guba, E.G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4(2), 97-128. Sage Publications.

Lubicz-Nawrocka, A. (2019). An introduction to student and staff co-creation of the curriculum, Teaching Matters blog – Promoting, discussing and celebrating teaching at The University of Edinburgh. An introduction to student and staff co-creation of the curriculum – Teaching Matters blog (ed.ac.uk)

Merriam, S.B. (2001). Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 89, 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.3

Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344603252172

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5-12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401

Mezirow, J. (1990). How critical reflection triggers transformative learning. In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Fostering critical reflection in adulthood (pp. 1-20). Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education Quarterly, 28(2), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171367802800202

Nilsson, M., Andersson, I., & Blomqvist, K. (2017). Coexisting needs: Paradoxes in collegial reflection—The development of a pragmatic method for reflection. Education Research International, 2017, 1-12. doi:10.1155/2017/4851067

Smith, E. (2011). Teaching critical reflection. Teaching in higher education, 16(2), 211-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.515022

Taylor, E.W. (2017). Critical reflection and transformative learning: A critical review. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning, 26(2), 77-95.

Valli, L. (1997). Listening to other voices: A description of teacher reflection in the United States. Peabody Journal of Education, 72(l), 67-88. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje7201_4

Van den Berg, G. & Du Toit-Brits, C. (2023). Adoption and development of OERs and practices for self-directed learning: A South African perspective. Teacher Education for Flexible Learning Environments (in press).

Wallin, P., & Adawi, T. (2018). The reflective diary as a method for the formative assessment of self-regulated learning. European Journal of Engineering Education, 43(1), 507-521. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2017.1290585

White, S., Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflection: A review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care (pp. 3-20). Open University Press.

Yamagata-Lynch, L., Click, A., & Smaldino, S. (2013). Activity systems as a framework for scaffolding participant reflections about distance learning in an online instructional technology course. Reflective Practice, 14, 536-555. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.809336

York, C.S., Yamagata-Lynch, L.C., & Smaldino, S.E. (2016). Adult reflection in a graduate-level online distance education course. Reflective Practice, 17(1), 40-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2015.1123686

Authors

Geesje van den Berg is a full Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies at the University of South Africa (UNISA) and a Commonwealth of Learning Chair in open distance learning (ODL) for Teacher Education. Her research focuses on student interaction, academic capacity building, openness in education, and teachers’ use of technology in ODL. She holds a DEd in Curriculum Studies and has published widely as a sole author and co-author with colleagues and students in ODL and curriculum studies. She leads a collaborative academic capacity-building project for UNISA academics in ODL between Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg in Germany and UNISA. She is the programme manager of the structured Master’s in Education (ODL) programme and has supervised numerous master's and doctoral students. Email: vdberg@unisa.ac.za (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0306-4427)

Patience Kelebogile Mudau is an Associate Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies, College of Education, UNISA. She teaches two modules of the MEd in Open Distance learning (ODL), Curriculum Development in ODL and Management in ODL. She is involved in coordinating the Online Teaching and Learning Certificate of Advanced Studies (CAS), emanating from the Memorandum of Agreement between UNISA and Oldenburg universities. Her research interests are Open Distance e-Learning, Open Education Practices, and technology-enhanced learning. Email: mudaupk@unisa.ac.za (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5389-6942)

Cosmas Maphosa is a Full Professor of Education Management and holds a Doctor of Education degree in Education Management. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Open and Distance Learning with the University of South Africa. He has worked in the higher education sector since 2003 as a lecturer, researcher, senior academic development practitioner, senior lecturer, Associate Professor and Full Professor. He is currently the Director of the Institute of Distance Education at the University of Eswatini. He has published one book, six book chapters and one hundred and thirty-five journal articles in accredited scientific journals to date. Prof Maphosa has, to date, successfully supervised fifteen full-thesis PhD candidates. His research interests are in education management, curriculum development as well as open and distance e-learning. Email: cmaphosa@uniswa.sz (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7818-4271)

Samuel Amponsah is an Associate Professor and heads the Distance Education Department of the University of Ghana. Prior to joining the University of Ghana. He was a fellow of the GCRF/LJMU digital Fellowship and was a Postdoctoral Fellow with the American University in Cairo supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation through BECHS-Africa Scheme. Samuel is an Adjunct Associate Professor for the University of South Africa, a Visiting Fellow at Liverpool John Moores University and a Visiting Lecturer for Birmingham Christian College in the UK. His research focuses on adult learning, open distance learning and inclusive education. Email: samponsah@ug.edu.gh (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5559-3139)

Blandina Manditereza holds a PhD in Curriculum Studies from the University of the Free State, where she lectures in Childhood Education. She obtained her First MEd and then Honours in Educational Management (Cum Laude) from the Central University of Technology. Currently, she is studying for a MEd Open Distance Learning (ODL)at the University of South Africa. In addition, she holds a BTech in Education Management from Tshwane University of Technology, a Diploma in Primary Education from Nyadire Teacher’s College, Zimbabwe, and a Certificate in Special Education Needs from Bradford and Ilkley Community College, Bradford, UK. Her research areas of interest include the following: Early Childhood, Curriculum Studies, and Language Teaching. Email: bmanditereza@yahoo.co.uk (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2564-5860)

Jennifer van der Merwe is a Learning Experience Design Partner at Zutari, an infrastructure, engineering and advisory practice. Before joining the world of consulting, Jennifer worked in Higher Education as the Head of Instructional Technology and Design at Regenesys Business School. Her master’s research focussed on the empowerment of working student mothers through distance learning, and she is currently enrolled for her PhD in Open Distance Learning at the University of South Africa. Jennifer received the Council Award for the best performance in a Master’s Degree (Coursework) in the College of Education for the academic year 2022. Email: jennifer900119@gmail.com (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0336-9423)

Stephen Mongwe is a UNISA Master’s of Education in ODL graduate. He is employed at the University of the Witwatersrand as a Health Sciences Faculty administrator in the Postgraduate Office. He worked in a variety of divisions before moving to the Health Sciences Faculty, including the Student Equity and Talent Management Unit and the International Students Office. Email: Stephen.mongwe@wits.ac.za (Orcid: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-3197-7853)

Cite this paper as: van den Berg, G., Mudau, P.K., Maphosa, C., Amponsah, S., Manditereza, B., van der Merwe, J., & Mongwe, S. (2023). Critical reflection by mature students as co-developers of an Open Educational Resource in foregrounding their learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 10(3), 316-332.