2024 VOL. 11, No. 3

Abstract: The use of Short Messaging Service (SMS) for education has grown in recent years, drawing particular attention to supporting school-level learners, due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This renewed interest has prompted questions about how this form of educational technology could be used in the longer term. However, despite being used in many Covid-19 responses, there are few documented examples of innovative applications in this field during the pandemic, which represents a gap in the literature. As a medium for education, SMS offers potential benefits such as being cost-effective and having positive impacts on learning. In this paper, we present a case study of an educational programme rapidly implemented during the pandemic as part of the ‘Keep Kenya Learning’ initiative, to support learners remotely in terms of literacy, numeracy, and social and emotional learning topics. Through the case study, we describe the innovative process used to rapidly develop content for SMS, and draw upon usage statistics, quiz scores and user feedback to gain insights into its implementation with learners and caregivers in Kenya. The case study demonstrated that educational television content can be effectively adapted to mobile delivery. Furthermore, we present practical reflections on the development and implementation of SMS educational technology which will help inform future initiatives. These include considering timing in relation to school terms when planning a supporting intervention, and designing content in a modular way to allow flexibility for learners in navigating through courses.

Keywords: Covid-19, distance education, mobile learning, SMS

When the Covid-19 pandemic took hold across the globe in early 2020, school closures and suspension of in-person educational provision were one of the most consistent and widespread policy responses (Hale et al., 2021). In response to school closures, educational content and support was often made available through a combination of radio, television and online platforms, in a bid to reach as many learners as possible (Vegas, 2020). In addition to more broadcast forms of educational technology, the use of mobile phones and messaging was also adopted, in some instances, as a low-connectivity and high-ownership medium (Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel, 2022; World Bank, 2020).

In Kenya, school closures were in effect from March 16, 2020, with remote learning initiated a week later; this included educational provision through television, radio, and the internet (Ngware & Ochieng, 2020). However, the extent to which learners could access remote learning across Kenya during the pandemic was variable. Overall, an average of 22 in every 100 children engaged with remote learning provision (Uwezo, 2020). Furthermore, there were stark differences in terms of socio-economic factors such as the type of school attended (Uwezo, 2020). Rates of access differed according to the medium involved, with television being used the most, and internet-based resources the least (Uwezo, 2020). Notably, within Kenya, there were much greater levels of mobile phone ownership compared to internet access, with 98% mobile phone penetration compared to 43% for internet (Cotter Otieno & Taddese, 2020). Furthermore, levels of access — particularly internet access — varied considerably between urban and rural areas (Cotter Otieno & Taddese, 2020). The shift to remote learning also placed parents and caregivers in a key role in supporting and facilitating their children’s learning (Osorio-Saez et al., 2021). The Uwezo survey found that on average, two in ten caregivers were not aware that their children were expected to engage with remote learning at home during the Covid-19 school closures, and that levels of parental awareness varied substantially according to different counties (Uwezo, 2020).

The Keep Kenya Learning (KKL) initiative was launched in 2020 with these contextual factors in mind, in order to “set clear expectations for parents and caregivers of what learning at home should look like and provide them with access to digital and non-digital resources to support those learning experiences” (Keep Kenya Learning, 2020, para. 4). To help achieve this goal, M-Shule became a partner in the KKL initiative. Meaning ‘mobile school’ in Kiswahili, M-Shule is an SMS-based educational platform that engages with learners and caregivers in Kenya through mobile phones in order to deliver educational content without requiring an internet connection. To date, the platform has reached approximately 20,000 households from 30 Kenyan counties, mainly to improve primary school children’s foundational learning (UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2022).

In this research, we present a case study of the rapid development and implementation of new content as a pilot study through the M-Shule learning platform as part of KKL. While the potential of SMS to support learning in low-connectivity contexts has been highlighted in the literature, there is a substantial gap in terms of published cases of its use in practice (Jordan & Myers, 2022). Although this study is relatively small-scale, it will help to address this gap. We draw upon two main forms of data and information: first, feedback and reflections from stakeholders involved in the process; and, second, server log information about how and when learners interacted with the content.

In this research, we focused on reporting the development and implementation of a pilot initiative, developed rapidly to support learners by mobile phone in Kenya in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. While it does not adopt a full evaluative research design, it is nonetheless an example which may be useful to the broader field of learning for development, as accounts exploring the use of low-connectivity educational technology in a challenging context are few. A case study approach is appropriate here as it is reporting a unique initiative in a particular set of circumstances; while the research goal is not to generalise or evaluate, the practical experiences of developing educational technology may be transferable to other contexts (Tight, 2017).

The research here was framed as a descriptive case study, with a primary goal of describing the case as situated within its own context (Merriam, 1998; Yin, 2008). The boundary of the case was defined as the development of m-learning materials as part of the KKL initiative. Case study research is not prescriptive in its approaches to data collection; rather, multiple sources appropriate to the context are typically used (Thomas, 2021). In this instance, we drew upon documents related to the development process, usage data generated by the system, and feedback from users. A total of 632 learners were invited to use the initiative. The sample was stratified to draw upon the user base from each of the partner organisations involved. The 632 comprised 332 from KKL, 200 from M-Shule, and 100 from Ubongo. Data about their levels of use of the initiative was collected through M-Shule system usage logs. At the end, a short evaluative feedback survey was administered through a combination of SMS and telephone calls. As a descriptive case study, the ‘Results and Discussion’ section adopts a narrative form, first outlining the context and development process, before describing the implementation and information about use.

The KKL initiative was launched in 2020 in response to the educational pressures of Covid-19 school closures in Kenya, and to help support caregivers and learners at home. The collaboration utilised the EdTech Hub’s ‘sandbox’ approach to rapid design, implementation and iteration (Boujikian et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2021). This model involved structuring activities around ‘sprints’, during which data was collected to understand stakeholders’ perspectives in relation to an intervention (Boujikian et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2021).

The first sprint focused on understanding the barriers and levers to engage parents and caregivers to support learning at home (Busara, 2020; Mbatha et al., 2021). The findings showed that caregivers were keen to assist their children, and that SMS could potentially be a good medium for providing support. In the second sprint, the provision of videos and SMS resources to help support caregivers and develop their digital literacy skills were shown to have a positive impact upon their self-efficacy (Kimathi et al., 2021).

Given that the findings from the sprints highlighted the importance of SMS as a familiar and accessible medium, there was a clear rationale for further examining the potential for SMS to be used as part of Keep Kenya Learning. M-Shule partnered with Ubongo in order to convert educational content from the Akili and Me television programme into SMS delivery. Akili and Me is an animated educational television programme, which is broadcast across 40 countries in Africa (Watson & McIntyre, 2020). Akili and Me is designed for younger children, with Ubongo Kids for older children. The impact on learning outcomes of the Akili and Me educational television programmes have previously been validated through a number of studies conducted in individual countries. For example, gains in terms of a range of skills including mathematics, literacy and health knowledge have been demonstrated in Tanzania (Borzekowski, 2018) and Rwanda (Borzekowski et al., 2019). Ubongo Kids has also been demonstrated to lead to learning gains in mathematics in Tanzania (Watson et al. 2021). Furthermore, watching Akili and Me and Ubongo Kids videos has also been shown to be effective in terms of social and emotional outcomes in Tanzania (Cherewick et al., 2021; Kauffman et al., 2022).

Technical development included both adapting the content from a video-based format to SMS and the development of the data dashboard to view learners’ interaction and progress with the content. Three topic areas were selected: numeracy, health and hygiene, and social and emotional learning (SEL). Each consisted of five subtopics. Content digitisation and product development were undertaken rapidly and collaboratively between the Ubongo and M-Shule team during April 2021. SMS messages were sent to sensitise caregivers and learners ahead of implementation, with a launch at the end of April 2021. The main pilot implementation was carried out over the course of three weeks, and up to three SMS reminders were sent per week to promote engagement.

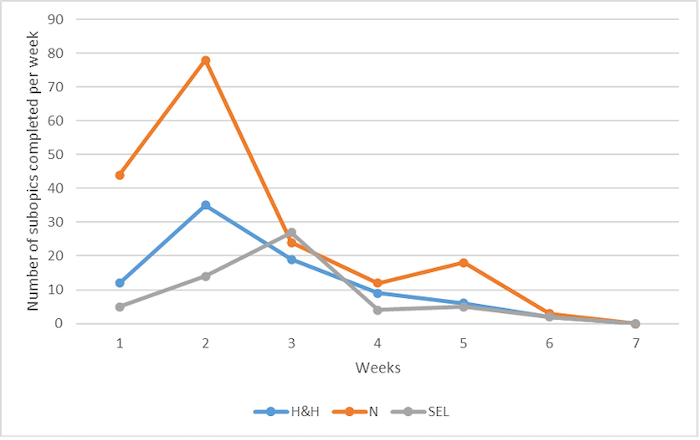

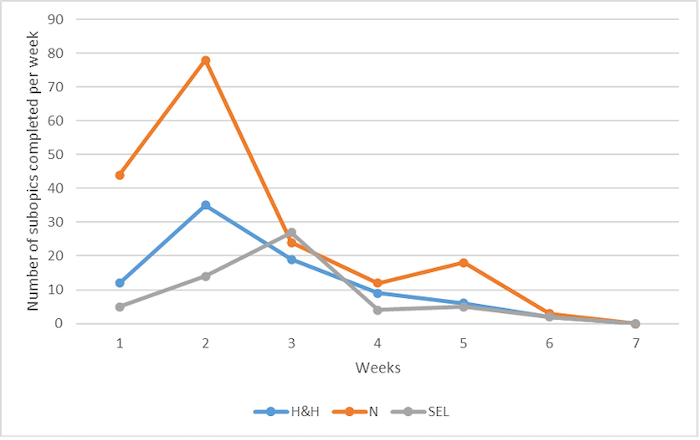

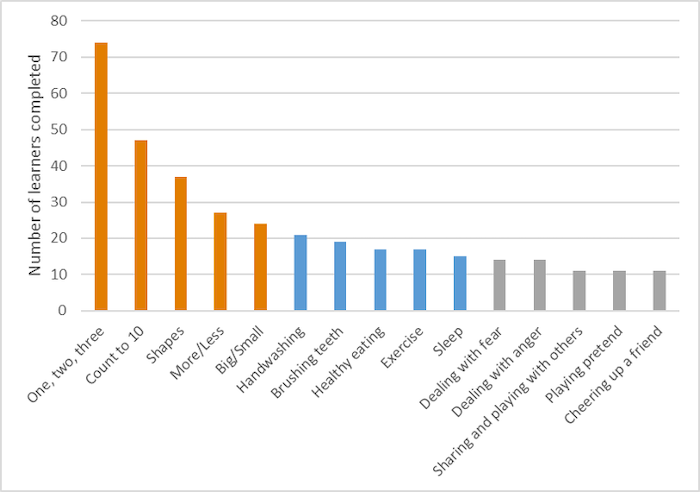

Of the 632 learners included in the sample, 135 (21%) accessed the content and 74 (12%) studied at least one subtopic mini-lesson to completion. The number of subtopics completed per week over the course of the pilot implementation is shown in Figure 1 (note that an individual student could take the same subtopic more than once).

The topics were presented to learners in a fixed order — first numeracy, followed by health and hygiene, and, finally, Social and Emotional Learning (SEL). The number of learners who fully progressed through the topics and subtopics is shown in Figure 2. Of those who had initially engaged with the content (135), 11 (just under 10%) completed the whole course during the implementation timeframe, with much higher levels of engagement in the first two weeks. This trend is in keeping with other similar platforms (Kizilcec & Chen, 2020). While the trend shown in Figure 2 demonstrates disengagement by most learners after four weeks, the implementation was intended to last for only a month, and the trend is consistent with findings from other studies of mobile and online learning, such as data from the use of the Shupavu291 product with learners in Kenya (Kizilcec & Chen, 2020). Although this case study focuses on a relatively small-scale implementation, if the trend were to be sustained at scale, active use by 10% of the users could still have substantial benefits. It is also notable that the longer-term data showed that some learners used the content again in October, which reflects the findings from Shupavu291 that learners may re-engage with content — after initial disengagement — when it would benefit them to do so (Chen & Kizilcec, 2020).

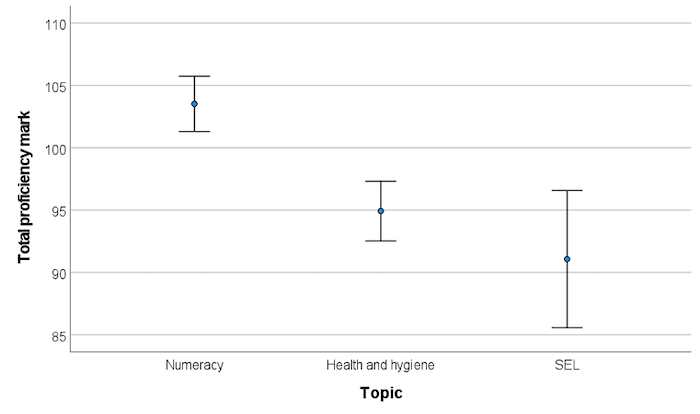

The average quiz scores logged showed notable differences between numeracy in comparison to health and hygiene or SEL, with higher scores observed in numeracy (Figure 3). Note that fewer learners completed health and hygiene and SEL quizzes than numeracy. This may also suggest that designing quiz questions for these topics is more challenging.

To gain further insight into the data, a user feedback survey was carried out by phone and SMS. Practical feedback concerning planning implementation was also received, which could potentially help enhance the number of learners engaging with the content in the future. This included suggestions to align the launch with a favourable time in the school term, which was particularly challenging during the post-Covid period as term dates were liable to change. Other recommendations include allocation of more resources for the onboarding process and allowing a longer implementation period for the users to learn how to navigate the platform and learn.

In this case study, we have reported findings and reflections from the rapid development and implementation of novel educational content intended to support learners and caregivers at home during periods of school closure in the Covid-19 pandemic in Kenya. As a case study, the study did not address specific research questions but rather its contribution lies in the reflections on design and implementation. In this concluding section, we draw together practical implications from the case which has been presented.

First, the case demonstrates that a ‘sandbox’ approach can be used in order to develop educational content for SMS delivery on an expedited timescale. The initiative moved rapidly from initial user research during the first sprint (Busara, 2020), to full adaptation of educational content for SMS and its implementation by the third sprint in a matter of months, during challenging pandemic circumstances. Building upon the insights from the earlier ‘sprints’ in the Keep Kenya Learning initiative, the successful implementation and use confirmed that caregivers were keen to engage and that this was a viable way to reach additional learners. It should also be noted however that a proportion of learners and caregivers who were invited to take part did not engage with the content, which could have been for a number of reasons, related to the pandemic or otherwise, and the data here does not help address why. For future work, it would be helpful for follow-up work to gain further insight into the participants’ perspective, to look at reasons for not engaging in more detail and ways to mitigate this. Recent survey research in Kenya has suggested that caregivers may have concerns about risks related to the use of mobile phones for educational purposes (Watson et al., 2023), which could be addressed as part of sensitisation. From a design perspective, engagement could be enhanced by including a longer period of sensitisation and onboarding.

Second, the pilot implementation demonstrates proof of the concept that health and hygiene and social and emotional learning topics can be successfully adapted for SMS. Numeracy has been widely studied in relation to educational technology (Jordan & Myers, 2022) and specifically SMS (Angrist et al., 2020; Jordan, 2023). Literacy is also often a focus in educational technology evaluations (Jordan & Myers, 2022). However, other topics — particularly social and emotional learning — are less well studied, but may, in turn, enhance outcomes in foundational subjects (e.g., Lichand et al., 2022). While this study has shown that SEL topics can be adapted to an SMS format, the question of how to optimise quizzes for subjective topics such as SEL may be a focus for further development (see Figure 3). Recent research in other contexts has shown that integrating SEL support in mobile learning, alongside foundational subjects can enhance learning outcomes across other subjects (Lichand et al., 2024). It may be valuable for this model, of combining SEL provision with foundational subjects, to be considered and developed further when designing future interventions.

The third main finding from the case study relates to practical considerations when designing an intervention in the future. Based on the user feedback and drop in usage levels as schools reopened, transferable insights included consideration of timing in relation to school terms, length and sensitisation when planning an implementation. The time period of the intervention was relatively short, and allowing more time for sensitisation and for users to become accustomed to the new content would be a key area for design in the future. Given the patterns of engagement seen with this (Figures 1 and 2) and other SMS platforms, it would also be useful to design content in modular ways to give learners more flexibility in accessing topics they require, in their choice of order. Designing modules in a non-linear way would also be useful if learners wanted to revisit content at different times during the school year (Chen & Kizilcec, 2020).

While the Keep Kenya Learning initiative was devised in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the acute effects of the Covid-19 pandemic upon access to education have now passed, the use of mobile phones to support learning in low-connectivity contexts may be used to reach learners who would benefit from extra support, or to engage caregivers in supporting their children alongside formal schooling (Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel, 2022). The use of SMS as a delivery mode has advantages in particular for low-connectivity areas of Kenya, where mobile device ownership is high (Jordan et al., 2023). Recent developments in mobile learning, such as Keep Kenya Learning, also potentially offer a greater level of preparedness and a scalable, cost-effective way to reach learners in case of future disruptions to in-person schooling, such as pandemics, strikes or environmental factors (Angrist et al., 2022). Furthermore, it reflects a broader trend in the use of educational technology being used to enhance parental engagement in addition to formal schooling (Nicolai et al., 2023).

In addition to the implications for the design of educational technology, the research also opens up areas for future research. It would be valuable to follow up on the relationship between television and mobile phone-based content (this was indicated in the feedback and relates to a gap identified by Watson and McIntyre, 2020). Current research is underway in collaboration between Ubongo and EdTech Hub to examine the use of SMS nudges and quizzes to promote engagement with educational television broadcasts at home (Katumbi et al., 2023), for example. Finally, follow-up research would be particularly useful to evaluate the impact of the content in terms of learning outcomes, both investigating the effects in terms of foundational learning gains and also the effects of including SEL topics.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Dr Mary Otieno and Jennifer Cotter Otieno for reviewing a draft of this paper. We are very grateful to those involved in the Keep Kenya Learning initiative, and would like to thank Education Design Unlimited for their collaboration on this work and for permission to access the collected data for secondary analysis. This analysis was funded through the work of EdTech Hub (http://www.edtechhub.org) and we gratefully acknowledge their support. Many thanks to all of the caregivers and learners who have used the M-Shule platform and participated in the Keep Kenya Learning initiative.

Angrist, N., Bergman, P., Brewster, C., & Matsheng, M. (2020). Stemming learning loss during the pandemic: A rapid randomized trial of a low-tech intervention in Botswana. SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3663098. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.3663098

Angrist, N., Bergman, P., & Matsheng, M. (2022). Experimental evidence on learning using low-tech when school is out. Nature Human Behaviour, 6, 941-950. DOI: 10.1038/s41562-022-01381-z

Boujikian, M., Carter, A., & Jordan, K. (2022). The Sandbox Model: A novel approach to iterating while implementing an emergency education program in Lebanon during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Education in Emergencies, 8(3), 215-228. DOI: 10.33682/rj45-k7z7

Borzekowski, D.L.G. (2018). A quasi-experiment examining the impact of educational cartoons on Tanzanian children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 54, 53–59. DOI: 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.11.007

Borzekowski, D.L.G., Lando, AL., Olsen, S.H., & Giffen, L. (2019). The impact of an educational media intervention to support children’s early learning in Rwanda. International Journal of Early Childhood, 51(1), 109-126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00237-4

Busara. (2020). Key insights from behavioral journey mapping of caregivers. EdTech Hub. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1l6-co7N-eWifjKXmkhEmcpze7TdpCfLr7QSQ4w4D8vo/

Chen, M., & Kizilcec, R.F. (2020). Return of the student: Predicting re-engagement in mobile learning. Proceedings of the 2020 Educational Data Mining Conference, July 10th-13th. https://educationaldatamining.org/files/conferences/EDM2020/papers/paper_95.pdf

Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., Richards, L., Njau, P.F., & Dahl, R.E. (2021). Adolescent, caregiver and community experiences with a gender transformative, social emotional learning intervention. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 55. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-021-01395-5

Cotter Otieno, J., & Taddese, A. (2020). EdTech in Kenya: A rapid scan. EdTech Hub. DOI: 10.5281/ZENODO.3909977

Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (2022). Prioritizing learning during COVID-19: The most effective ways to keep children learning during and post-pandemic. World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/114361643124941686/recommendations-of-the-global-education-evidence-advisory-panel

Hale, T., Angrist, N., Goldszmidt, R., Kira, B., Petherick, A., Phillips, T., Webster, S., Cameron-Blake, E., Hallas, L., Majumdar, S., & Tatlow, H. (2021) A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour, 5, 529-538. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01079-8

Jordan, K. (2023). How can messaging apps, WhatsApp and SMS be used to support learning? A scoping review. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 32(3), 275-288. DOI: 10.1080/1475939X.2023.2201590

Jordan, K., Damani, K., Myers, C., Mumbi, A., Khagame, P., & Njuguna, L. (2023) Learners and caregivers barriers and attitudes to SMS-based mobile learning in Kenya. African Education Research Journal, 11(4), 665-679. DOI: 10.30918/AERJ.114.23.088

Jordan, K., & Myers, C. (2022). EdTech and girls education in low- and middle-income countries: Which intervention types have the greatest impact on learning outcomes for girls? Proceedings of the Ninth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, 330-334. DOI: 10.1145/3491140.3528305

Katumbi, L., Baraza, B., & Vu, C.P. (2023). Enhancing children’s learning with edutainment—Can following set TV schedules make a difference? EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/2023/11/20/enhancing-childrens-learning-with-edutainment/

Kauffman, L.E., Dura, E.A., & Borzekowski, D.L.G. (2022). Emotions, strategies, and health: Examining the impact of an educational program on Tanzanian preschool children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), Article 10. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph19105884

Keep Kenya Learning (2020). Keep Kenya Learning website. https://web.archive.org/web/20201101023228/https://keepkenyalearning.com/

Kimathi, D., El-Serafy, Y., Plaut, D., & Kaye, T. (2021). Keeping Kenya learning: The importance of caregiver engagement in supporting learning beyond the classroom. EdTech Hub. https://edtechhub.org/2021/07/16/keeping-kenya-learning-the-importance-of-caregiver-engagement-in-supporting-learning-beyond-the-classroom/

Kizilcec, R.F., & Chen, M. (2020). Student engagement in mobile learning via text message. Proceedings of the Seventh ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, 12th-14th August, 157-166. DOI: 10.1145/3386527.3405921

Lichand, G., Christen, J., & van Egeraat, E. (2024). Neglecting students’ socio-emotional skills magnified learning losses during the pandemic. NPJ Science of Learning, 9(28), 1-11. DOI: 10.1038/s41539-024-00235-9

Lichand, G., Christen, J., & van Egeraat, E. (2022). Neglecting students’ socio-emotional skills magnified learning losses during the pandemic: Experimental evidence from Brazil. SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3724386. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.3724386

Mbatha, F., Crook, R., & Plaut, D. (2021). Keep Kenya Learning: Helping caregivers support learning at home, sprint 1. EdTech Hub. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4928926

Merriam, S.B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

Ngware, M., & Ochieng, V. (2020). EdTech and the COVID-19 response: A case study of Kenya. EdTech Hub. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4706019

Nicolai, S., Rui, T., Zubairi, A., Seluget, C., & Kamninga, T. (2023). EdTech and parental engagement. Background paper prepared for the 2023 Global education monitoring report: Technology in education: UNESCO. DOI: 10.54676/BFFW8873

Osorio-Saez, E.M., Eryilmaz, N., & Sandoval-Hernandez, A. (2021). Parents’ acceptance of educational technology: Lessons from around the world. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. DOI: 10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2021.719430

Rahman, A., Carter, A., Plaut, D., Dixon, M., Salami, T., & Schmitt, L. (2021). The Sandbox Handbook v1.0: A guide to growing and testing EdTech ideas. EdTech Hub. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.5120788

Thomas, G. (2021). How to do your case study (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Tight, M. (2017). Understanding case study research: Small-scale research with meaning. SAGE.

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. (2022). M-Shule SMS learning & training, Kenya. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. https://uil.unesco.org/case-study/effective-practices-database-litbase-0/m-shule-sms-learning-training-kenya

Uwezo. (2020). Are our children learning? The status of remote-learning among school-going children in Kenya during the COVID-19 crisis. Nairobi: Usawa Agenda. https://web.archive.org/web/20220211093137/https://palnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Usawa-Agenda-2020-Report.pdf

Vegas, E. (2020). School closures, government responses, and learning inequality around the world during COVID-19. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/school-closures-government-responses-and-learning-inequality-around-the-world-during-covid-19/

Watson, J., Baier, J., Mughogho, W., & Millrine, M. (2023). An exploratory investigation into the factors related to EdTech use among Kenyan girls. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(4), 1006-1024. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.13307

Watson, J., Hennessy, S., & Vignoles, A. (2021). The relationship between educational television and mathematics capability in Tanzania. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(2), 638-658. DOI: 10.1111/bjet.13047

Watson, J., & McIntyre, N. (2020). Educational television: A rapid evidence review. EdTech Hub. DOI: 10.5281/ZENODO.4556935

World Bank. (2020). How countries are using edtech (including online learning, radio, television, texting) to support access to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

Yin, R.K. (2008). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). SAGE.

Author Notes

Dr Katy Jordan is a Lecturer and Co-Director of the Centre for Technology Enhanced Learning at Lancaster University, UK. Her research spans the use of technology in a range of educational contexts, with particular interest in relation to digital scholarship, open education and equity. Email: k.jordan@lancaster.ac.uk (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0910-0078)

Albina Mumbi is a business development consultant at M-Shule. A graduate of The Catholic University of East Africa, she has both passion for and experience working with communities to ensure they have sustainable solutions to their challenges. Email: albina.mumbi@m-shule.com

Phoebe Khagame is a dynamic professional with a strong passion for social impact. Her experience spans education and healthcare in several African countries, where she has excelled in strategic operations and in-country as well as regionally-focused initiatives. She was previously Head of Operations at M-Shule, and is a board member of EdTech East Africa. Email: phoebe.khagame@m-shule.com

Lydia Njuguna is a project management and business development professional, previously at M-Shule. She is an accomplished Sociologist with professional training in project management and experience in leadership roles within the education technology, media and customer experience domains. Email: lydia.njuguna@m-shule.com

Cite as: Jordan, K., Mumbi, A., Khagame, P., & Njuguna, L. (2024). Low-connectivity educational technology: A case study of supporting learning during Covid-19 via SMS with ‘Keep Kenya Learning’. Journal of Learning for Development, 11(3), 553-562.